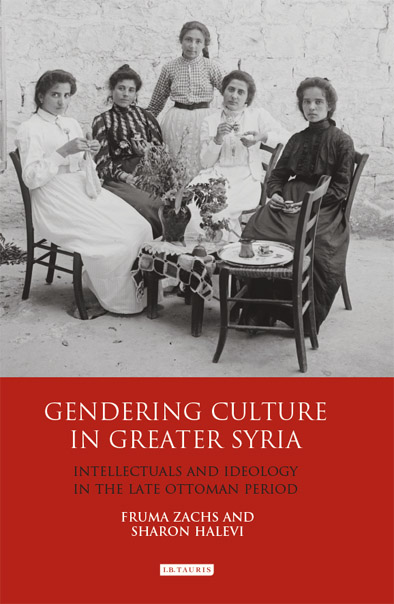

Fruma Zachs is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Middle East History at the University of Haifa, Israel. She is the author of The Making of a Syrian Identity: Intellectuals and Merchants in NineteenthCentury Beirut and co-editor of Ottoman Reform and Muslim Regeneration (I.B.Tauris).

Sharon Halevi is a Senior Lecturer and Chair of the Womens and Gender Studies Program at the University of Haifa, Israel. She is the editor of The Other Daughters of the Revolution and author of Revolutionary Selves (forthcoming).

GENDERING

CULTURE IN

GREATER SYRIA

Intellectuals and Ideology in the

Late Ottoman Period

F RUMA Z ACHS AND S HARON H ALEVI

Published in 2015 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright 2015 Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi

The rights of Fruma Zachs and Sharon Halevi to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by the authors in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Earlier versions of Chapter 1 and Chapter 2 appeared respectively as From Difa al-Nisa to Masalat al-Nisa in Greater Syria: Readers and Writers Debate Women and their Rights, 18581900, International Journal of Middle East Studies 41: 4 (2009): 61534 (reprinted with permission), and Asma (1873): The Early Arabic Novel as a Social Compass, Studies in the Novel 39: 4 (2007): 41630 (reprinted with permission by Johns Hopkins University Press. Copyright 2007 by the University of North Texas).

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to gain permission for the use of the images in this book. Any omissions will be rectified in future editions.

References to websites were correct at the time of writing.

Library of Middle East History 51

ISBN: 978 1 78076 936 3

eISBN: 978 0 85773 672 7

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

For my parents, Rachel and Pesach Schreier

Fruma

For my parents, Sylvia and Samuel Ezekiel

Sharon

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Sketch showing the appropriate table setting. Source: Farida Hubayqa, Adab al-Maida, al-Muqtataf 9 (1884), p. 370.

Asma, the heroine of the novel Asma. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 29.

Badia, the villain of the novel Asma. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 65.

Sketch showing the detrimental effects of the corset on the internal organs. Source: Anonymous, al-Mishadd, al-Hilal 5 (1896), p. 136.

Badi is the villain of the novel. He is vain, self-centered, and immoral. Although he is interested in marrying Asma, she is repulsed by his personality. His posture reflects his character. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 127.

Karim al-Baghdadi is the hero of the novel. He is a well-educated, generous, and upstanding young merchant, and at the end of the novel he marries Asma. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 101.

Jalil is Asmas brother (and her male counterpart). Jalil courts Badia but eventually marries Saada, since she embodies the feminine qualities promoted by the novel. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 173.

Farid is another scoundrel. He courts several young women over the course of the novel but eventually ends up with Badia. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 281.

Farid scheming with his servant. His bearing indicates laziness and immorality. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 381.

Sada is the young woman who eventually marries Jalil. She symbolizes innocence, kindness and orderliness. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 209.

Nabiha is one of the minor female characters in the novel. She is mesmerized by everything Western but understands the merits of her own culture. Source: Salim Al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 245.

Do I look European? Nabiha showing off her new dress and shoes to her European fianc (Richard). Nabiha is so eager to flaunt her new matching shoes that she does not notice she has lifted her skirt so much that the dress is now immodestly short. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 281.

Karim and Asma. In this image they are contrasted with Nabiha and Richard. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 713.

Nabiha and Richard taking a stroll to impress onlookers. Nabiha was so impressed by Richards beret that she asked him to wear it at home as well. Source: Salim al-Bustani, Asma, al-Jinan 4 (1873), p. 677.

Letter from al-MuqtatafVol. 20 (1896), pp. 1989. Published in the section: al-Munazarawal-Murasala A Public Debate and Exchange of Letters.

NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

When transliterating from Arabic, we follow the system used in the International Journal of Middle East Studies. Diacritical marks are omitted, but the ayn () and hamza () are retained. We do not transliterate place names, but leave them as they are commonly rendered. Arabic first and last names are transliterated, but most foreign-language proper names are not, even if they deviate from the system of transliteration. For claritys sake we sometimes translate the titles of articles from the Arabic press into English.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It is always a pleasure to thank those who have supported and encouraged our work. We would particularly like to thank Amer Karkabi and Manhal Zreik, from the Periodicals Department of the University of Haifa Library, for their invaluable assistance in finding and pointing out items of particular interest and answering our questions. Our colleagues Butrus Abu-Manneh, Ami Ayalon, Basilius Bawardi, Yuval Ben-Bassat, Orna Blumen, Amalia Levanoni, Vardit Rispler-Haim, Holly Schissler, Reuven Snir, Mechal Sobel, Ibrahim Taha, and several anonymous readers read earlier versions of this work and raised several issues we had not fully considered; we could not have hoped for a better group of commentators.

We also wish to thank the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute for generously funding and hosting our two-year research group, The Novel as a New Framework for Thinking about the Middle East in the Modern Period, and, of course, its members who joined us in this endeavor to retrace the impact of the fictional on the factual. The Research Authority of the University of Haifa generously contributed to the funding of this research. Esther Singer deserves special thanks for her careful editing of the book. We would also like to express our appreciation to Maria Marsh and Azmina Siddique from I.B.Tauris Publishers who oversaw the project and who responded to our needs and concerns quickly and efficiently.

Finally, we would like to thank our families, who tolerated our endless discussions on this book even in the midst of social and family occasions.

Next page