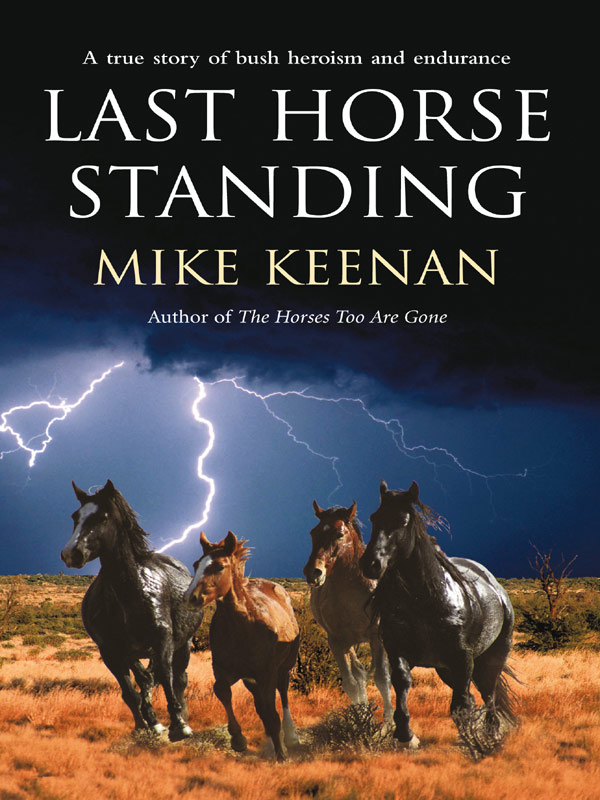

ALSO BY MIKE KEENAN

The Horses Too Are Gone

Wild Horses Dont Swim

In Search of A Wild Brumby

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968 ), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Last Horse Standing

ePub ISBN 9781742742823

Kindle ISBN 9781742742830

Authors note: Some names have been changed to protect the privacy of individuals.

LAST HORSE STANDING

A BANTAM BOOK

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2006

by Bantam

Copyright Michael Keenan, 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Keenan, Michael, 1943.

Last horse standing.

ISBN 978 1 86325 579 0.

ISBN 1 86325 579 6.

1. Wilderness survival Western Australia Kimberley

Biography. 2. Droving Western Australia Kimberley

Biography. 3. Cattle trade Western Australia Kimberley

Biography. 4. Kimberley (W.A.) Biography. I. Title.

919.414

Transworld Publishers,

a division of Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney, NSW 2060

http://www.randomhouse.com.au

Random House New Zealand Limited

18 Poland Road, Glenfield, Auckland

Transworld Publishers,

a division of The Random House Group Ltd

6163 Uxbridge Road, Ealing, London W5 5SA

Random House Inc

1745 Broadway, New York, New York 10036

I wish to dedicate Last Horse Standing to Peter Wann,

his wife Ngaire and their two daughters Jenna and Kayla.

CONTENTS

SUMMARY OF REPORTS IN THE WEST AUSTRALIAN , MARCH 1971

An intense tropical rain depression crossed the west Kimberley coast on 22 March. The Fitzroy River had a sudden and spectacular rise, recording thirty-seven feet at Fitzroy Crossing one day later. All roads in the district were cut and the river village was caught with little food. The airstrip was closed and a further five inches of rain fell on 24 March.

On 26 March the bureau of meteorology at Perth issued a warning that Cyclone Mavis had formed, was 300 miles wide and, due to high sea temperatures (80F), it would probably intensify to a category two or three. The cyclone moved off the coast and appeared to be heading away from the mainland, but on 27 March it suddenly altered course and struck the coast at Hamelin Pool, a long way south for a tropical cyclone. On 29 March some of the heaviest rain in memory fell across large areas of Western Australia, washing away rail lines and bridges. A day later heavy stock losses were reported and food was airdropped to stranded motorists. At Shark Bay, boats broke their moorings and a major sea swell damaged the town.

In the archives of the Perth Weather Bureau, Cyclone Mavis is described as one of the longest-running cyclones in Western Australian history.

Overview of the West Kimberley coast and adjacent inland region.

Route taken by Jack Camp in 1971, from Oobagooma to Panter Downs.

The eastern tip of Walcott Inlet from Mt Talbot to the old Munja Reserve.

I FIRST HEARD about Jack Camps amazing story at Beagle Bay in October 2002. Nearly everyone who visits Broome for a holiday gets to hear about the Catholic church at Beagle Bay, built by priests from the German Palatine Order in 1918. This exquisitely beautiful church has no equal in outback Australia. Under the guidance of the priests, Aborigines made the mud bricks for the new church and collected the tens of thousands of seashells used in its decoration. They were from the language groups of the Jabirryabirr, Nyulnyul and, to the north, the Bardi people. My first connection to this story was Bardi man, Otto Dibley. Although not in the traditional land of his people, Otto settled in Beagle Bay before he died in the late 1980s.

Ottos name tumbled out from desultory conversation with a local Elder. My wife and I had visited the church, Sal had taken some photos and we were about to drive the 130 kilometres back to Broome. I have never been shy to talk to strangers and over a mug of tea from a thermos I asked the Elder if his people worked the surrounding country with cattle. He was seated on the ground, leaning against the trunk of a tree. The only shop was nearby and the local people loved to sit around and yarn. The Elder had been talking to a couple of women while he waited for his wife who was in the store. Despite his age, he was handsome with long grey hair and a slightly Malay appearance.

He didnt answer me directly. When he launched straight into the past I knew the cattle days were long gone. He told us he was reared at the mission and later got a job as a deckhand on the Watt Leggit , a lugger that operated out of Derby carrying supplies to remote settlements on the west Kimberley coast and returning with lepers destined for the leprosarium. Leprosy is a disease obscure in Australian frontier history and I asked him where the worst affected area was.

The Munja community at Walcott Inlet, he replied. The police patrols brought in the sick and locked them up in a big compound, to await the lugger.

I mentioned having heard Walcott Inlet had spectacular scenery and that I was hoping to go there some day soon.

His eyes narrowed to him, I was just another tourist who knew nothing about the dark decades of the Kimberleys, that part of the history either lost or destroyed. Walcott Inlet had been the meeting place for the tribes. Now there was no one there, not a living soul.

In my time, he said, Walcott was the destination for the sick. The women there had no young, and crocodiles took more men there than anywhere else on the coast. I suppose we blackfellas would call it the land of the devil devil, he shrugged and smiled. Its nonsense I know, but it became that sort of place. I had a good friend called Otto Dibley. Hes gone now, but he had this story about a white man and his boys caught in a willy willy at Walcott. Otto left them before the big storm to get more supplies, they were branding cattle. He got caught too and for a month battled flooded rivers, no food, and when he got to a place called Oobagooma a white lady gave him food and spare horses to rescue those white people. But a white man pulled a gun on him and stopped him. Otto never made it back.