The first two histories of that illustrious bastion of yachting the Royal Yacht Squadron, were called Memorials. Whether or not this was because the members of those days were already dead in their wicker chairs, they do reveal Victorian and Edwardian yachting as being both hilarious and eccentric. A third history, written by myself, was published recently; it not only showed that things have not changed that much at the Castle, but that there was an urgent necessity for an alternative look at our senior, though not our oldest, yacht club.

This deeply researched book, conducted with the help of a substantial number of pink gins, shows a lighter side to an institution which, for getting on for two centuries, has dominated the sport of yachting in Britain.

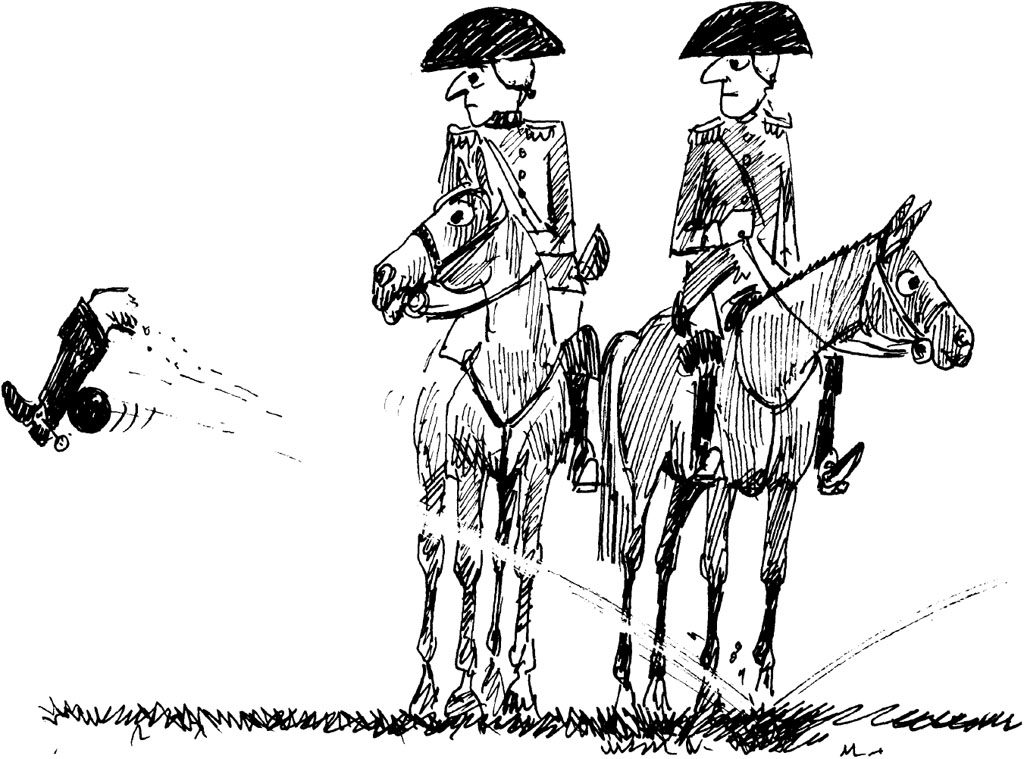

One of the founding members of the Squadron, at first called simply The Yacht Club, was the Earl of Uxbridge, later the Marquess of Anglesey. The first meeting to inaugurate the new club was held on 1 June 1815, but the Earl was not present as he was leading a division of cavalry at Waterloo. It was during this famous battle that the Earl lost a vital part of himself. By God! he exclaimed to the Duke of Wellington after a volley of French cannon shot had blasted the area, I have lost my leg! The Dukes reply was brief: Have you, by God!

The Marquess was extremely proud of the whiteness of the decks of his cutter Pearl, and when a guest left footmarks on it after a rain shower he instructed one of his crew to trail him and wipe them off as he walked.

The sequel to the story of the Marquess losing his leg at Waterloo did not emerge for some decades. Some time during the 1890s the Dukes grandson, also a Squadron member, related to another member the story of his grandfathers leg. He lost it at Waterloo, the Dukes grandson explained. Oh, said his friend, on which platform? The grandson was much disgusted by this ignorance of history and went across the room to complain about it to another friend of his. Do you know, he said, when I told that my grandfather had lost his leg at Waterloo, he asked on which platform it had happened! His second friend looked sympathetic. The mans an idiot. As if it mattered which platform.

Guess what the following was all about.

The gallant Sir James Jordan, who was on board Mr Maxses, had a narrow escape from a dreadful blow aimed at the back of his head by one of Mr Welds men with a handspike as the two vessels were touching each other. He avoided the blow by ducking his head, and hitting out right and left la Spring, floored the rascal with such tremendous violence that Captain Lyons told me afterwards he thought he was done for.

An encounter during the Napoleonic Wars, or a meeting with pirates perhaps? No, just a yacht race in the Solent during 1826 when the Arrow collided with an opponent. The racing was very keen in those daysif keen is quite the right word.

The 110 ton cutter Scorpion was a typical racing yacht of the 1820s. Just in case she met an opponent like the Arrow during a race, she was well equipped with four brass cannon and an armoury of rifles, pistols and cutlasses.

In the early days the few yachts which were built were modelled on Revenue cutters, and sometimes on the even faster smugglers vessels which often evaded them. The Marquess of Anglesey, determined to have built the fastest yacht possible, asked whom he should approach to construct it. He was told that Philip Sainty of Wivenhoe was the best man for the job, as he not only built fast boats for carrying contraband but was a confirmed smuggler himself. The only trouble was that Sainty had been locked up in Springfield jail. This did not deter the Marquess at all and he persuaded the King to grant Sainty a free pardon. Sainty, however, was as wily as he was talented and refused to leave jail until his brother and brother-in-law were also freed, so the Marquess had to get all three out of jail before he could get his yacht built.

The Squadrons first Commodore, Lord Yarborough, had a full-rigged ship as his yacht. Falcon was manned by a crew of 54 who had all signed a paper agreeing to be flogged if the need arose. Modern winch-grinders please note.

Some of the early systems of handicapping devised by the club were bizarre. In 1831 the citizens of Cherbourg offered two cups to be raced for by the clubs yachts, and it was decided to give a time allowance by starting the smallest yacht first and the largest last, an absurd arrangement over a course of only 24 miles. The French quite failed to understand the proceedings and after the race had finished were heard enquiring when it was about to begin.

Early members of the club thought of themselves as a kind of auxiliary squadron for the Royal Navy, a notion that existed for many years. In 1827 when the Royal Navy was fighting the battle of Navarino, who should turn up but the club Commodore in his yacht, determined to make himself useful. The yacht was apparently used as a despatch vessel, but the Admiral commanding the battle got so tired of the Commodore asking for missions that he sent him off with a message to the captain of a frigate most remote from the Admirals flagship. The message read, Give his Lordship a good meal and hell give you a better one in return.

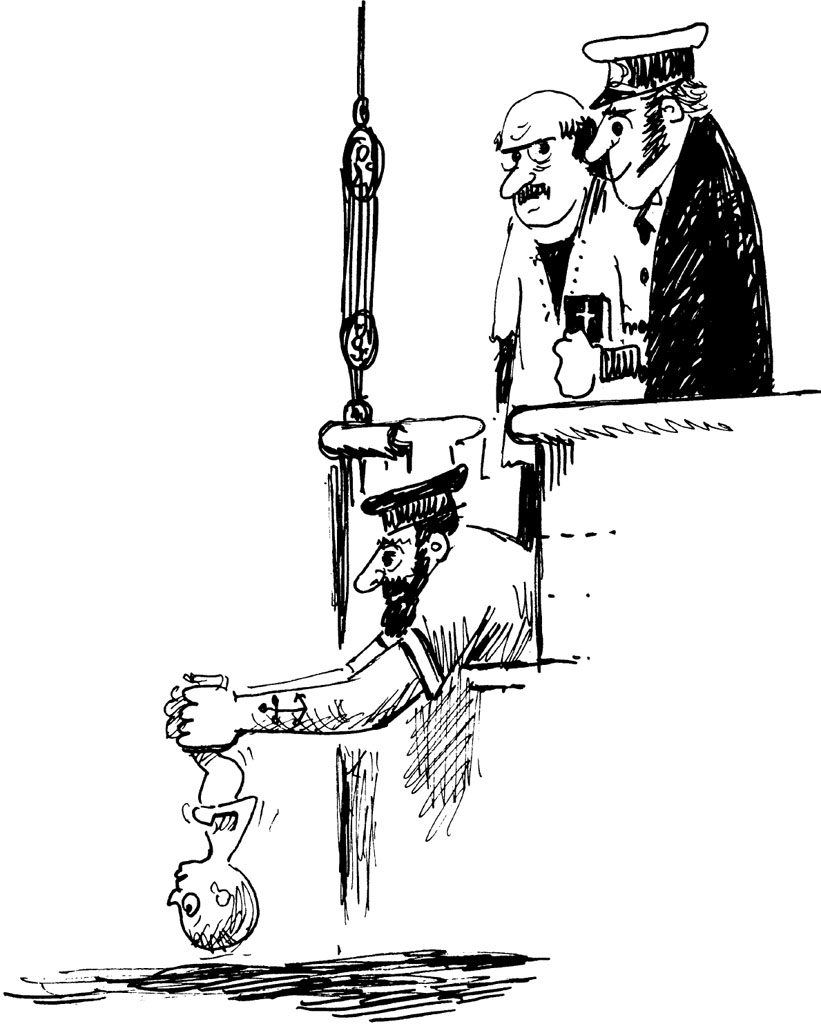

The Marquess of Anglesey was a real old sea dog. He had his son Lord Alfred Paget christened by having him dunked head-first into the sea from the deck of his yacht, surely the most unusual method yet employed for introducing a baby to religion.

Signalling by flags between yachts was obviously an OK thing to do, for one of the first acts of the new club was to publish a signals book. The system was reworked over a number of years, until by 1831 the book was a large compendium which enabled members to signal messages like Have you any ladies on board? to one another. Signals could also be sent ashore, and among those listed were demands for one hundred prawns to be sent to the yacht concerned; there was also half a column on the 14 different types of wine which could be ordered.

At least one member found the signals book rather confusing. He had just concluded a rough passage to Torbay and the bowsprit of his yacht was broken and her deck in total disarray. When he was seen by a group of club yachts lying at anchor in the bay, in immaculate condition awaiting the start of the local regatta, a signal was raised asking for his club number. The distraught owner ran up the correct flags but in the wrong order, so that his message read Can I render you any assistance?, which caused great amusement among the other members.

It was only in Victorian times that blackballing became a common procedure. In its early days the club only blackballed on two occasions. Once was when the Duke of Buckingham failed to renew his subscription and was rejected on applying for reelection; and again when someone who owned a yacht that looked like a river barge was excluded. It was reported that this curious vessel, part of which was made of brick, had taken two months to sail from the Thames to Cowes, and members excluded her owner more as a joke than anything else.