A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

ISBN 978-1-988516-60-8

ePub ISBN 978-1-988516-74-5

Mobi ISBN 978-1-988516-75-2

An Upstart Press Book

Published in 2020 by Upstart Press Ltd

Level 6, BDO Tower, 1921 Como St, Takapuna

Auckland 0622, New Zealand

Reprinted 2020

Text Tom Scott 2020

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Design and format Upstart Press Ltd 2020

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Designed by Nick Turzynski/Redinc. Book Design, www.redinc.co.nz

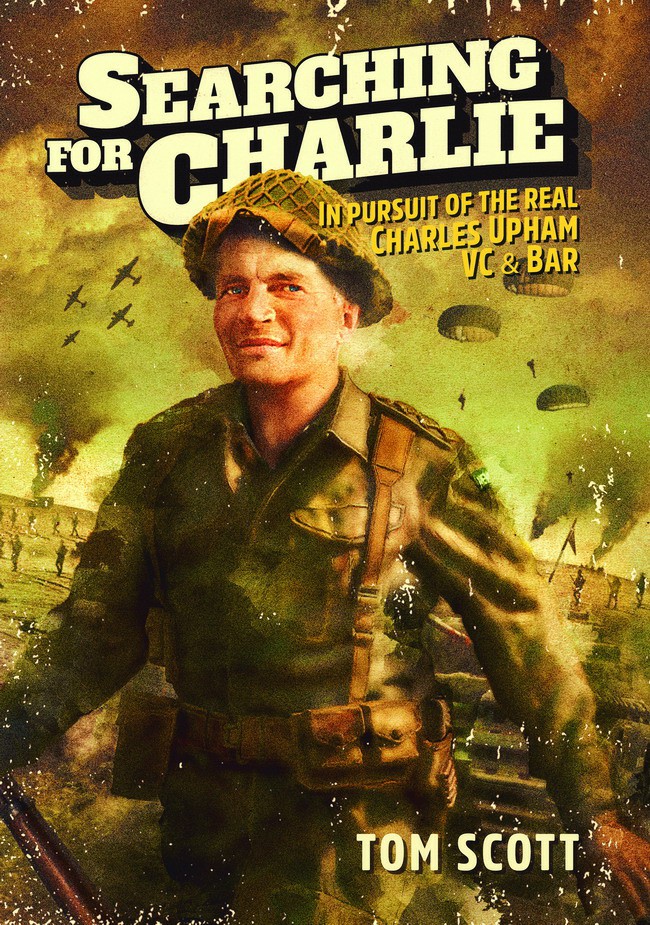

Cover illustration by Mardo El-Noor

Jacket and front endpaper photos: Charles Uphams VC & Bar and Group. Credit: National

Army Museum Te Mata Toa, Waiouru

Back endpaper photo: Charles Upham statue, Amberley, North Canterbury, New Zealand. Credit: Tom Scott

Printed by Everbest Printing Co. Ltd, China

Publishers disclaimer: Although every effort has been made to supply accurate credits for the images reproduced in this book, due to the exceptional circumstances pertaining during the 2020 Covid-19 lockdown in New Zealand over the course of production, it was not possible to verify archival sources with complete certainty in all cases.

Contents

Authors note

I walked hill trails to Mt Everest, had afternoon tea with the Dalai Lamas spiritual advisor in a remote Nepalese monastery on the border with Tibet, interviewed Sir Edmund Hillary at the South Pole for a television documentary, traded emails with the first man on the moon, Neil Armstrong, about appearing in another documentary about Ed (they were friends and, after a lot of equivocation, he eventually declined to participate).

I attended the UN General Assembly with two New Zealand prime ministers, dined with Indira Gandhi at Hyderabad House in Delhi, and enjoyed hefty gin and tonics on the royal yacht Britannia and wrote this book solely because my father met a bunch of New Zealanders in a Munich bar after the war who were cut from the same cloth as Charlie Upham.

My father was in the Bavarian capital serving in the RAF as part of the Allied Forces of Occupation and remembered the New Zealand troops fondly. They were big raw-boned bastards who wore shorts in all sorts of weather and didnt lord it over the locals like some of the other occupation troops. He was in a bar one night when a barman refused to serve a Maori soldier, saying that they didnt serve monkeys. Even fifteen years later, my fathers Northern Irish brogue danced and his eyes lit up with delight recounting what happened next: He wanted to let it go, but his Pakeha mates took exception and tore the place apart completely wrecked the joint and when British Military Policemen came running to restore order in their distinctive helmets and white puttees, waving their long batons and blowing their whistles, the Kiwis kicked the snot out of them as well. Then, as casual as you like, they strolled next door and ordered another round. Jesus, it was impressive!

It was straight out of the Charlie Upham playbook bullying and bullies needed to be confronted and challenged head on. Intolerance would not be tolerated. Mad dogs needed to be shot!

The New Zealanders egalitarian instincts, disgust with racism and casual disdain for authority appealed to my father. He wanted to be on that team. When his tour was over, he went to the New Zealand High Commission in London and enlisted in the Royal New Zealand Air Force.

Once the paperwork was finalised, he set sail for New Zealand and was posted to Ohakea Air Force Base in the Manawatu in New Zealands lower North Island. A year later when our paperwork was sorted, my mother Joan, my twin sister Sue and I set sail to join him.

This book is dedicated to the New Zealand soldiers who so impressed my father. I did not grow up in Belfast, Bristol or Birmingham, and so was not denied the freedoms, privileges, advantages and opportunities that life in Aotearoa has afforded me. Thank you, Charlie, and every Kiwi soldier, sailor, airman, doctor, nurse and chaplain who journeyed from the bottom of the world to help rid the world of a monstrous evil.

Tom Scott

Wellington

Prologue

Wind beats heavy on the borderline between tussock and scree. Swirling snowflakes dance past two black circles. A dropping jaw reveals a flash of pink.

A newborn lamb bleats. Her dead mother is vanishing beneath a carpet of white. A rider is approaching, dogs begin to howl. Hat pulled low, pipe clenched upside between his teeth, he nudges his mare up a rocky slope, dismounting when it becomes too steep. Darting nimbly between boulder and tussock, he reaches the shivering lamb. Cleaning mucus from its nostrils, he tucks it inside his jacket. He whistles to his dogs and waiting mare. The ewe that he thought was dead gurgles. Pink bubbles blister her lips. He takes out the knife sheathed at his waist and with a single swift stroke cuts her throat. Arterial blood spurts across pristine snow. Taking off his hat, he nods his head, marvelling at the mysterious line between life and death that all living things fight furiously to avoid crossing.

As he heads back across a high saddle, the snow turns to stinging rain. Eagle-eyed, he spots a distressed ewe nuzzling a dead lamb. He dismounts, pulling his knife from his belt. Unhappy and agitated, the ewe circles as he deftly skins her lamb and fashions the bloody pelt into a woolly overcoat for the orphan wriggling inside his jacket. It fits snugly. The ewe sniffs the imposter cautiously. Hell stick around a bit to see if the fraud works.

He presses fresh tobacco into his pipe. His mare and dogs shelter from the storm in the lee of a large outcrop of rock and look on with idle curiosity. Maternal longing eventually overwhelms suspicion and the ewe lets the lamb suckle. His handsome face lights up in a smile. Its craggy like a sackful of chisels. He is not yet twenty-six but looks older. He is joined silently by his dogs. He is wet through to the skin, so saturated he could be swimming. He could sleep rough in these clothes if he had to. Caught too far from a hut after dark, sometimes hed done just that. Besides, the rain had eased off. It was light rain now. Dry rain he called it. Not many understood the concept. Meteorologists didnt. But hed had a blazing row or two in smoko rooms and public bars over this paradox. Only another shepherd or musterer understood the notion, and he suspected many of them only agreed with him for the sake of a quiet life. Stuff em! he grins.

Back in the cobb hut, he lights the cast-iron stove. Thick walls made from a mixture of clay, tussock and manure provide excellent insulation. Every stockman, fencer and rabbiter in this neck of the woods will tell you these huts have good hats and dry feet. You cant ask for more than that. He throws dried peas, whole onions and curry powder into a pot of disgusting cold, grey, congealed mutton stew to freshen it. His dogs creep nearer in anticipation of leftovers. There will be plenty. All a man really needs is two feeds a day and a warm, dry place to sleep. This is his mantra. Not that he would call it that. He just says it often.

Overhead the skies clear. His guts rumble. He is busting for what a Maori shearer mate calls a cave-in. He wont be incorporating that into his vocabulary. His prim mother finds his new vernacular shocking enough as it is. He heads out to the long-drop under heavens milky with stars. A long trail of leaping flame turns his hurricane lamp into an Olympic torch. The glass globe went west yonks ago. Up here toilet paper comes in two brands: