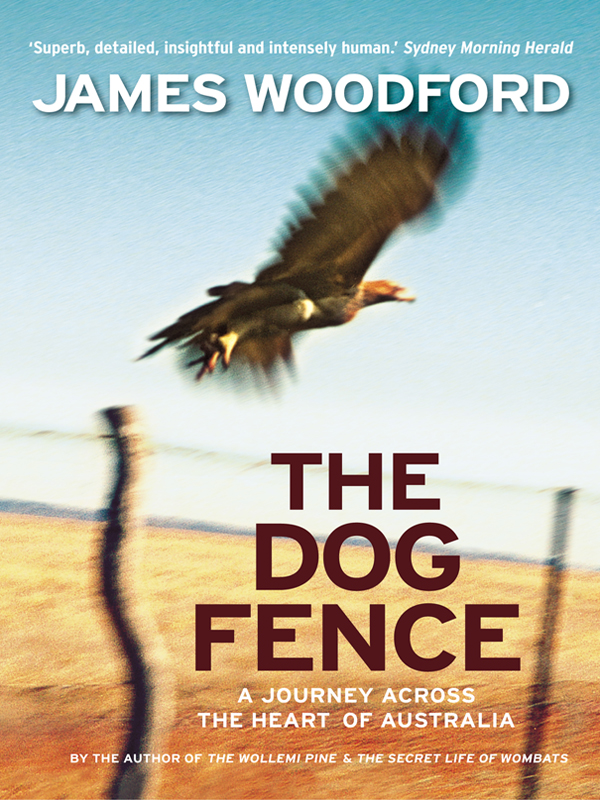

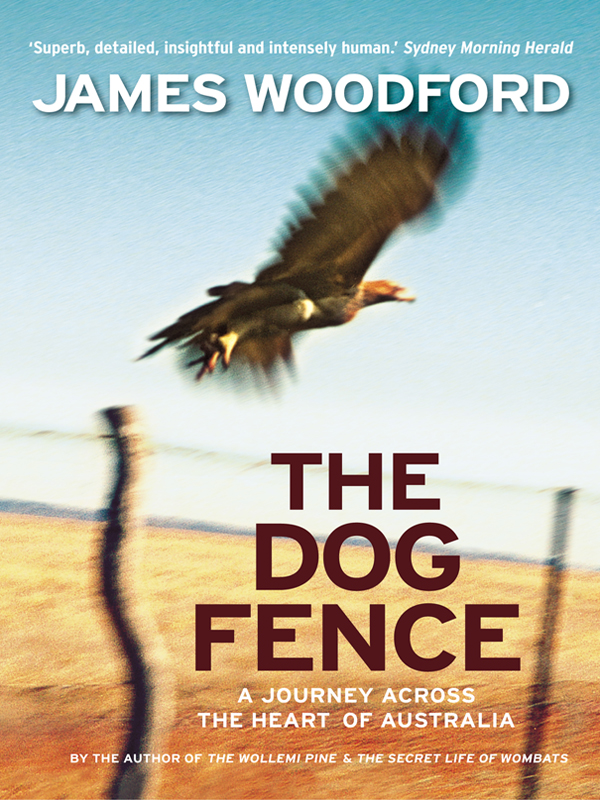

PRAISE FOR JAMES WOODFORD

THE WOLLEMI PINE

The Wollemi Pine is a fascinating mix of detective story, scientific mystery and human dramaan engrossing read for expert and layperson alike. Australian Geographic

James Woodford has the enviable skill of presenting science in a way that draws the reader further and further into the book. Science by no means dominates the book, and can be lightly skipped by those who are more fascinated by the human events and personalities in this intriguing story. Canberra Times

Woodford skilfully recounts the story behind the story of the freakish survival, discovery and identification of the Wollemi pineit turns out to be a fascinating tale of high adventure and mystery, of rivalries and jealousies, of legal and political twists and turns. A scientific thriller.

Adelaide Advertiser

THE SECRET LIFE OF WOMBATS

Winner of the Whitley Award for Best Zoological Book of 2001

Outstanding. Tim Fischer

Ranging from quick lessons in paleontology to insights into wombat lifestyles and the sometimes rugged lives of scientists dedicated to their study, this is a great read for nature lovers.

Burkes Backyard

Woodford has done the research, he has read widely, spoken with the major wombat pundits and with the lay observers. He has travelled to gain direct experience of all species. His book has drawn together much of what is known about wombats, and perhaps all that the lay reader wants to know. Sunday Age

OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR

The Wollemi Pine

The Secret Life of Wombats

THE

DOG

FENCE

A JOURNEY ACROSS THE HEART OF AUSTRALIA

JAMES WOODFORD

The Text Publishing Company

171 La Trobe Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright 2003 James Woodford

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

Printed and bound by Griffin Press

Typeset in Centaur by J & M Typesetting

Designed by Chong Weng-ho

Maps by Tony Fankhauser

All photographs by James Woodford except for p. 111, reproduced with kind permission of Donald Byrnes, and p. 171 with kind permission of Alec Wilson.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Woodford, James, 1968-.

The dog fence.

ISBN 1 877008 76 1.

1. Feral dogs - Control - Australia. 2. Dingo - Control

Australia. 3. Fences - Australia. I. Title.

632.697720994

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

For Prue Woodford, her mothers daughter

A DANGEROUS TRACK

Permission is required to travel along the 5400-kilometre track which flanks the Dog Fence. Australias most remote road is not maintained for tourists and has numerous hazards for the inexperienced adventurer. It is so isolated that stops for fuel and water may be up to 1000 kilometres apart. Emergency assistance is impossible without adequate communication equipment, and pastoralists actively discourage visitors for fear of legal liability for any injuries, or fatalities, which may occur.

CONTENTS

M

We climb onward, towards the sky and with every step my spirits rise. As I walk along, my stave striking the ground, I leave the tragic sense of things behind; I begin to smile, infused with a sense of my own foolishness, with an acceptance of the failures of this journey as well as of its wonders, acceptance of all that I might meet upon my path.

Peter Matthiessen, The Snow Leopard

CHAPTER 1

CIVILISATIONS BOUNDARY

Where it begins, at the Great Australian Bight just west of Penong, the Dog Fence hangs out over the Southern Ocean, topped by a single pole that points down at a seaweed-covered rockshelf. The fence ends 5400 kilometres away in Queensland, but here in South Australia a tangled strand of wire holds a five-metre length of plastic mesh in place. Immense waves roll in from the south-west and the air is humid with salt spray.

The coast is a dramatic scar, left after Gondwana finally tore itself apart. Forty million years later the sea is still surging into the gap as Antarctica and Australia continue to drift apart. The ground has numerous holes and cracks, which puff and steam like a whales blowhole. Creep close to one of these enormous wormholes through the cliff and twenty metres below you can see a circle of the ocean, shining like a little silver eye.

It was February 2002 and I was about to begin a journey along the entire length of this extraordinary structure, designed to keep Australias wild dog, the dingo, out of the continents south-east corner where the richest grazing and pasture land is found.

I first crossed the fence in 1993 when I was in the Strzelecki Desert in New South Wales but, because of the sand dunes, I saw no more than a few kilometres of the structure. That day was the first I thought about travelling its length. My resolve hardened in 1995 when, while doing a story for the Sydney Morning Herald, I was falsely accused of spreading the rabbit calicivirus from its quarantine area in South Australia. At the time the leader of the National Party of Australia and future deputy prime minister, Tim Fischer, gave a press conference where he said, If proven, the reporter and photographer should be put to work on the Dog Fence between South Australia and New South Wales. The threat only fuelled my fascination.

Whenever I was west of the Great Dividing Range, looking at almost any barrier or even when daydreaming at my desk, I often thought of the wire wall. As far as I knew it was only 600 kilometres long. One slow day in spring 2001 I pulled out an Australian atlas and started turning the pages, following the structure with my finger from one map to the next until it tipped into the Southern Ocean.

From my starting point on the New South Wales border I then tried to do the same in the opposite direction, but as soon as the line on the map entered Queensland the Dog Fence disappeared. Where did it go? How was it that I had never known that the fence was so long?

A dingo would have to be able to abseil to cross the Dog Fence at its starting point where it hangs over the Southern Ocean.

Within an hour I had telephoned the New South Wales fence inspector, and by the end of the day I had written to the South Australian government and left a message for the Queensland boss. I had begun to plan my journey and intended on using the fence as a handrail through the heart of Australia. What sort of people would I meet? Would I be able to meet the challenges of the trip?

The desert runs hard up against the edge of the precipice and there is not a tree anywhere in sight, only saltbush, pigface, tough little grasses, rocks, boulders, pebbles and sand. Limestone coats this entire landscape like stucco for thousands of kilometres, and the ocean and the elements have carved the cliff-line into a craggy rampart. To the east are the Ocock Sandhills, which run along the coast for seven kilometres and stretch 1.5 kilometres inland. At heights of 100 metres the dunes are five times taller than the cliff where the Dog Fence starts. Beyond the cliffs, on the horizon, there seems to be an enormous ski field which is in fact more vast dunes, backing on to the fifteen-kilometre-long Dog Fence Beach. Only one spot looked safe for a dipa tiny bay west of the fence appeared to be the perfect place to roll out a towel and take to the water.

Next page