PRAISE FOR JAMES WOODFORD

THE WOLLEMI PINE

The Wollemi Pine is a fascinating mix of detective story, scientific mystery and human dramaan engrossing read for expert and layperson alike. Australian Geographic

James Woodfordhas the enviable skill of presenting science in a way that draws the reader further and further into the book.

Science by no means dominates the book, and can be lightly skipped by those who are more fascinated by the human events and personalities in this intriguing story. Canberra Times

A fascinating tale of high adventure and mystery, of rivalries and jealousies, of legal and political twists and turns. A scientific thriller. Adelaide Advertiser

THE SECRET LIFE OF WOMBATS

WINNER OF THE WHITLEY AWARD FOR BEST ZOOLOGICAL BOOK OF 2001

A surprisingly great readOutstanding. Tim Fischer

Ranging from quick lessons in paleontology to insights into wombat lifestyles and the sometimes rugged lives of scientists dedicated to their study, this is a great read for nature lovers.

Burkes Backyard

THE DOG FENCE

A graphic and compelling account of one of the worlds most bizarre yet least-known structuresWhat makes Woodford such a good reporter is his ceaseless curiosityThis book is the result.

Superb, detailed, insightful and intensely human.

Sydney Morning Herald

For anyone who loves the Australian bush, this book is irresistibleSome of the stories collected are as extraordinary as the fence itself. Courier-Mail

Woodfords cast of characters and his raw material vary with the bewildering richness of the Australian landscape. Australian

OTHER BOOKS BY THE AUTHOR

The Wollemi Pine

The Secret Life of Wombats

The Dog Fence

Whitecap

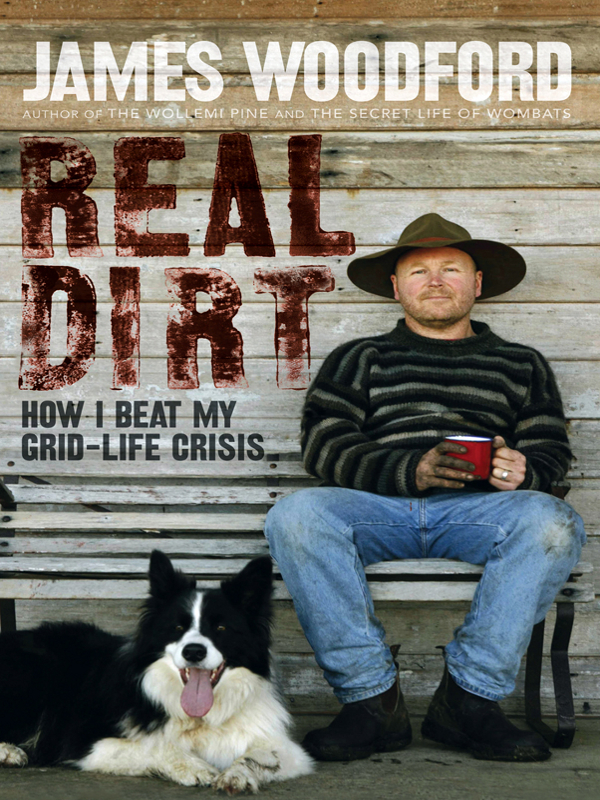

James Woodford is a writer and journalist. He runs the environment and sustainability website

www.realdirt.com.au

JAMES WOODFORD

REAL DIRT

HOW I BEAT MY GRID-LIFE CRISIS

TEXT PUBLISHING MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA

The paper used in this book is manufactured only from wood grown

in sustainable regrowth forests.

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

www.textpublishing.com.au

Copyright 2008 James Woodford

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by The Text Publishing Company 2008

Designed by W.H. Chong

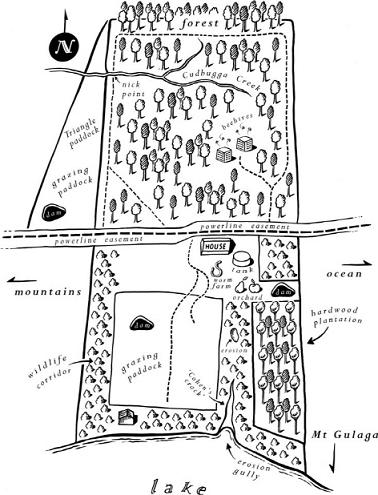

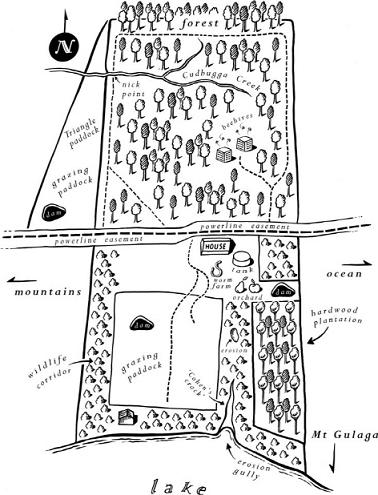

Map by Bill Wood

Photos courtesy of the author, except where otherwise credited

Typeset in Centaur 13.25/19 by J & M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Real dirt : how I beat my grid-life crisis / James Woodford.

ISBN: 9781921351792 (pbk.)

Woodford, James, 1968- -Anecdotes.

Sustainable living - New South Wales - Moruya Region - Anecdotes. Ecological houses - New South Wales - Moruya Region - Anecdotes. Country life - New South Wales - Moruya Region - Anecdotes.

333.72092

This project has been assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body

For Prue,

and for my grandfather, Rex David Hungerford.

Contents

The road beneath the giant original trees

sweeps on and cannot wait. Varnished by the dew,

its darkness mimics mirrors and is bright

behind the panic eyes the driver sees

caught in headlights. Behind his wheels the night

takes over: only the road ahead is true.

It knows where it is going: we go too.

Sanctuary, the sign said. Sanctuary

trees, not houses; flat skins pinned to the road

of possum and native-cat; and here the old tree stood

for how many thousand years? that old gnome-tree

some axe-new boy cut down. Sanctuary, it said:

but only the road has meaning here. It leads

into the worlds cities like a long fuse laid.

Judith Wright

It was January 2004, nearly dark, and I was stranded in the middle of a wild lake beside a capsized dinghy. There was a north-easterly gale blowing and no one knew I was in trouble.

This was self-sufficiency? A seachange? Life on the land? No. More like, what the hell am I doing here?

I knew I wasnt going to die, but I had to keep my wits about me. The lake was full of jellyfish and I was red with their stings. There were whitecaps breaking into my face so that I had to time my breathing; I was cold and getting colder; ropes and wires snaked all around in the water, waiting to snag me. I knew if I didnt concentrate until the cavalry arrived I could get into some serious trouble.

Id bought the boat a few months before. Our farm fronts onto a coastal lake on the New South Wales south coast and Id become nostalgic for a dinghy, an old gaffrigged Heron like the one I used to borrow with my friends from school, learning to sail in the sulphurous waters of the Parramatta River. In my Heron I would teach my children to sail, show them the thrill of power and speed without an engine you dont need jet skis and sleek speedboats with twin 125 horsepower engines to impress children, I told myself. They would always remember their summers learning to sail with their dad. The new boat was sold to me by a weather-beaten southern highlands cattle farmer who cried when he parted with it, and my fantasy was complete.

The only problem was that as a kid I had never really learned to sail. I had always been a crewman which in a Heron means, at the end of the day, ballast to stop the boat capsizing. Never mind: I would head out with my new boat only in fine weather. Id sail carefully around the bay in front of our land, aware of my limits.

But on that January afternoon the weather wasnt so fine. Prue and I were down on the lake by ourselves, all three children being looked after elsewhere, and the wind was a howling north-easter flecking the lake with whitecaps. Im going to have a sleep in the shack, Prue said. Why dont you go for a sail?

No chance. Its way too windy, I said, pointing at the lake and raising my voice above the noise of the wind and waves twenty metres away.

Wuss.

As soon as she was gone I walked down to the lake where the boat was pulled up on the sand. Wuss? I unfurled the jib, shoved off and scrambled aboard without a backward glance.

In calmer days: Sophie watches while I learn to sail my Heron

The Heron took off as if she had been flung from a catapult. Before I knew it I was crashing through the chop on the lake and half way across the bay, the wind shrieking and the sails sounding as if they could tear at any second. But worse was coming. A headland jutting into the lake marked the end of the bay: beyond that there was no protection whatsoever from the gale. I knew I had to turn around, but when I swung the tiller the boom came at me like Friar Tucks staff. The boat was instantly flipped on its side.

Next page