Praise for James Woodford

THE SECRET LIFE OF WOMBATS

Whitley Award Winner for Best Popular Zoology Book 2002

Shortlisted for the Colin Roderick Prize 2001

A revealing look at our most personable marsupials.

Sunday Mail

From quick lessons in paleontology to insights into wombat lifestyles and the sometimes rugged lives of scientists dedicated to their study, this is a great read for nature lovers.

Burkes Backyard magazine

Full of endlessly diverting informationWho would have thought that wombats had a secret life, let alone it being so interesting? And if you think the wombats are interesting you should

read about the people who study them!

Australian Bookseller & Publisher

A great success. Canberra Times

THE WOLLEMI PINE

A fascinating mix of detective story, scientific mystery and human dramaan engrossing read for expert and layperson alike.

Australian Geographic

James Woodfordhas the enviable skill of presenting science in a way that draws the reader further and further into the book.

Canberra Times

Compelling. Adelaide Advertiser

For Prue

and her love of nature

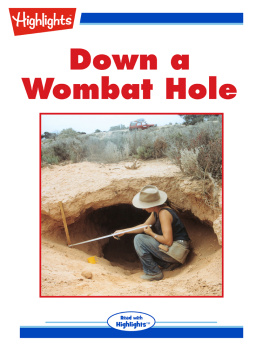

BEWARE

Never climb down into wombat burrows. They are unstable and full of poisonous animals such as snakes and spiders. Wild dogs use the tunnels as hiding places and wombats themselves are dangerous animals when corneredeasily able to crush intruders against the roof of their homes.

Chapter 1

WOMBAT BOY

The wombat is a buff to greyish-black, coarsehaired, thick-set animal about three feet long, and it stands only about one foot three inches high. It is heavy (often about 70 pounds in weight) and its weight is carried by its short, thick legs. It is very strong and when seen in a hurry looks like a tank as it takes all types of hills and gullies in its stride. It leaves a footprint like a foreshortened human footprint in mud or snow.

P ETER N ICHOLSON

By the time he reached the end of the burrow, the ball of twine that trailed behind fifteen-year-old Peter John Nicholson had shrunk from the size of a tennis ball down to that of an apple core. It was April 1960, a few months into the school year at Timbertopone of the most spartan schools in Australia. Only small signs indicate its location; a rough dirt road is the only way in. The Timbertop campus lies hidden at the base of the mountain. Just a few steps away from the grounds and a student could be lost for days.

NicholsonPJ or Peter John to his friends and many of his teacherswas playing truant from his dormitory. If caught he may have copped a caning, so he waited until after dark when he could hear that his fellow boarders were fast asleep. He dressed quietly, putting on rubber-soled hiking boots, an old long-sleeved khaki shirt and a tatty football jumper with padding on its elbows. His wombatting pants had patches on patches, so much so that he looked like a boy who had put on every pair of trousers he owned. At the exit to the dormitory he looked out into the night, checking for the red glow of a cigarette or any other sign of a master on the prowl for stray students. Teacher patrols, however, were mainly to prevent inter-dormitory raids and pranks. As long as Nicholson was on his own and keeping quiet, he was able to slip away easily, sneaking across the few illuminated metres between his building and the immense forest.

Another twenty metres and he was on the banks of Timbertop Creek, which he could jump, with one big bound. The waterway supplied the school and it was rich with platypuses and yabbiesa gurgling, crystal-clear stream with deep cold pools. Wombats lived all along its banks and had made useful trails for the exploring boy. He could disappear in seconds by walking up that creek, and from there he could access hundreds of square kilometres of virgin wilderness.

It was now about 9.30 p.m. It was very cold and he braced himself inside his wombatting clothes. Once on the other side of the stream he was free and alone with the forests nocturnals. His torch caught the red eyes of greater glidersflying marsupials, with charcoal fur and long agile tailson the boughs of the mountain-ash eucalypts. Weighing over one and a half kilograms and at over a metre in length, these marsupials spread the membrane of loose skin attached from their elbows to their ankles and can glide up to a hundred metres from tree to tree.

Grey kangaroos turned towards Nicholson but continued grazing as he strode past them. Feral dogs, cats and foxes had not yet penetrated the wilderness and the vegetation was dense with marsupials. There were no weeds, no rubbish, no pollution. The area teemed with wildlife, even in the middle of the day. From the moment hed arrived at the school in February, Nicholson had noticed and marvelled at the native animals. By the end of his first month he had already investigated more than twenty kilometres from his dormitory. When he and his friends stood outside their dorms for rollcall they could see the kangaroos boxing in the grassy areas beneath the giant trees. Kangaroos may have doe-like faces but during these matches they used their tails like the third leg of a tripod and were capable of tearing at each others chests until they were stained pink with blood. But it was the wombats which captivated him and lured him outside at night. His destination as he sneaked out of his bed was underground.

In the last month he had been casing one burrow in particular, getting to know its forks and offshoots, testing it for its stability, mapping it and slowly pushing further inside. He had been underground, fashioning turning points and widening routes in places where the tunnel became too narrow for him to pass. He avoided any major excavations though, mindful that the burrow had an occupant.

The boy, already 183 centimetres (six feet) tall and skinny, estimated from the twine still bundled in his hand that he was about ten metres underground. He felt compelled to keep wriggling forward; he couldnt resist exploring deeper and deeper. This was not the first time he had entered a wombat burrow, but this was the furthest he had yet travelled and he knew that he must be near whatever was living inside. He was entering the foundations of Mount Timbertop. His arms were thrust out in front of him and only a few centimetres lay between his back and the roof of the tunnel. He resembled a caterpillar in its cocoon and he was moving like one, dirt and grit gluing to him as he pushed forward.

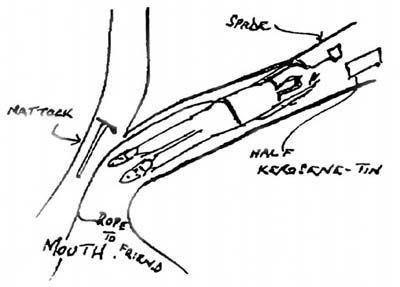

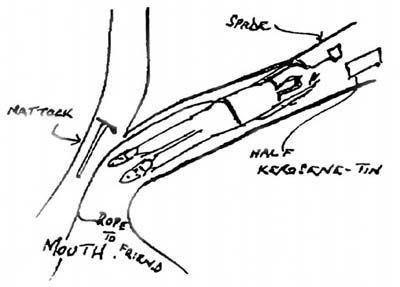

The long and lean Nicholson was a tight fit in a burrow, as shown here in his drawing of how he explored wombat homes.

It smelt earthynot bad at all, only a slight waft of vegetation. He was constantly surprised how clean the burrows were. Wombats, he had found, smell like the bushthey certainly didnt defecate underground. The occasional fibrous root swung in his path and Nicholson thought about the forest that was growing above his head. Thousands of tonnes of timber were separated from him by a ceiling of dirt just a few metres thick.

For a few seconds he turned off his torch and smiled to himself at the complete darkness he was travelling through. Without a light, the air was so black it was a sensation instead of a colour. He even imagined that he could see the electric messages firing around in his brain. It was the kind of darkness out of which anything a mind could conjure might spring; his fingers tightened around his heavy chrome torch which doubled as a club. On other trips he had used the top of a kerosene tin as a shield.