The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For Anne Ashby Gilbert, whose support and solidarity made this book possible, and for whom I have more gratitude than words can express

THE KENNEDY AND JOHNSON ADMINISTRATIONS, 196165

THE WHITE HOUSE

John F. Kennedy, president of the United States (196163)

Lyndon B. Johnson, vice president of the United States (196163); president of the United States (196369)

McGeorge Bundy, national security adviser (196166)

Theodore Sorensen, special counsel and adviser to President Kennedy (196163)

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., assistant to President Kennedy (196163)

Bill Moyers, assistant and press secretary to President Johnson (196367)

Douglass Cater, special assistant to President Johnson (196468)

Walt W. Rostow, deputy national security adviser (1961)

Michael V. Forrestal, staff member, National Security Council (196264)

Chester L. Cooper, staff member, National Security Council (196466)

James C. Thomson Jr., staff member, National Security Council (196466)

DEPARTMENT OF STATE

Dean Rusk, secretary of state (196169)

George Ball, undersecretary of state (196166)

W. Averell Harriman, ambassador at large (1961); assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs (196163); undersecretary of state for political affairs (196365)

Roger Hilsman, director, Bureau of Intelligence and Research (196163); assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs (196364)

William Bundy, assistant secretary of state for Far Eastern affairs (196469)

U. Alexis Johnson, deputy undersecretary of state (196164, 196566)

Walt W. Rostow, chairman, Policy Planning Council (196166)

Thomas L. Hughes, director, Bureau of Intelligence and Research (196369)

Frederick Nolting, U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam (196163)

Henry Cabot Lodge, U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam (196364, 196567)

Maxwell Taylor, U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam (196465)

John Kenneth Galbraith, U.S. ambassador to India (196163)

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

Robert S. McNamara, secretary of defense (196168)

Roswell L. Gilpatric, deputy secretary of defense (196164)

Cyrus Vance, deputy secretary of defense (196467)

William Bundy, assistant secretary of defense (196264)

John McNaughton, assistant secretary of defense (196467)

MILITARY OFFICERS

Lyman Lemnitzer, chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff (196062)

Maxwell Taylor, military representative to the president (196162); chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff (196264)

Earle G. Wheeler, chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff (196470)

Arleigh Burke, chief of naval operations (195561)

Paul D. Harkins, commanding general, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (196264)

William Westmoreland, commanding general, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (196468)

CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

Allen Dulles, director of central intelligence (195361)

John McCone, director of central intelligence (196165)

Richard Bissell, deputy director, Central Intelligence Agency (196162)

Ray Cline, deputy director, Central Intelligence Agency (196266)

OTHER OFFICIALS

Robert F. Kennedy, attorney general (196164)

Mike Mansfield, U.S. senator from Montana; Senate majority leader

J. William Fulbright, U.S. senator from Arkansas; chairman, Senate Foreign Relations Committee

Richard Russell, U.S. senator from Georgia; chairman, Senate Armed Services Committee

INTRODUCTION

LEGEND OF THE ESTABLISHMENT

The last time I saw McGeorge Bundy was on Wednesday, September 11, 1996. We met in midtown Manhattan for a working lunch in a private conference room of the Carnegie Corporation of New York, where Bundy was senior scholar in residence. How are you? he asked exuberantly as he entered the room, a stack of books and papers tucked under his arm. He seemed eager to begin our meeting.

I had been engaged in Bundys professional life for several years during the completion of my studies for a PhD in international relations at Columbia University. My first assignment with him was as the staff director of an international commission of diplomats and arms-control experts for which he served as chairman, leading a study on the United Nations Security Council and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. My second project with Bundy was more historical in nature. It was also far more personal.

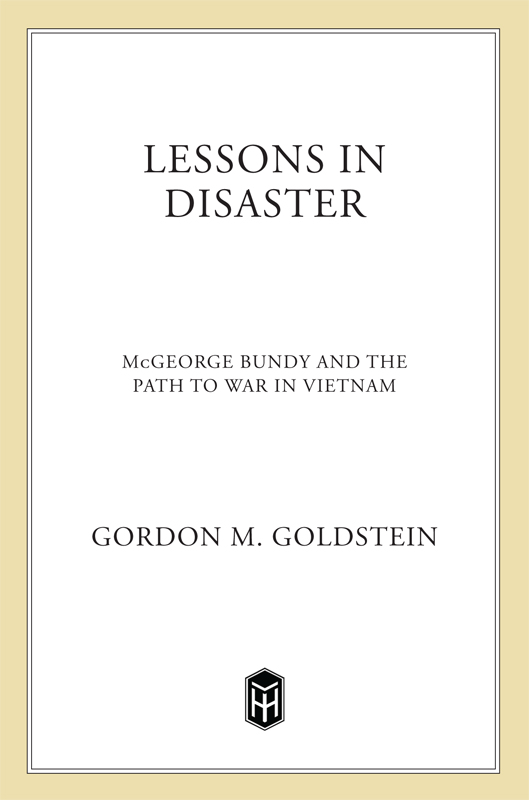

In the spring of 1995 Bundy asked me to collaborate with him on a retrospective analysis of the American presidency and the Vietnam War during his tenure as national security adviser to Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. We envisioned the book to be both a memoir of Bundys experience with Kennedy and Johnson as well as a reconstruction of the pivotal presidential decisions about American strategy in Vietnam between 1961 and 1965. As our collaboration progressed and we produced a shared thematic, interpretive, and organizational model of the book, I accepted Bundys proposal to be formally recognized as coauthor for a work to be published by Yale University Press.

In the year and a half we had worked in concert on the Vietnam project, Bundy and I had made significant substantive progress, encompassing all of the key historical inflection points and pivotal players in Vietnam policy during the Kennedy and Johnson years. Yet the actual text of the book was still inchoate, composed of scores of unique, individual passages of manuscript that Bundy had been drafting by hand. These so-called fragments were to be integrated with my research memoranda, outlines, and chronologies, as well as commentary extracted from the transcripts of my interviews with Bundy on a vast range of topics relating to the war. Individually these materials constituted the disassociated elements of an incomplete analytical history. Connected into a conceptual and chronological architecture, however, the fragments and research we were producing served as the foundation for what we hoped would be a meaningful contribution to the history of the Vietnam War.

As we met that afternoon, Bundy displayed an intensity that was different from what I had observed in countless hours of previous discussion. I had quite an argument with my brother, he announced, referring to William Bundy, who had served as a senior State Department and Pentagon official during the Vietnam era. Now I know Im right, he added, with a smile of discernible but good-natured mischief. Bundy spoke with great energy and focus for more than five hours, discoursing on a wide range of themes late into the day. There was a dramatic difference between Kennedy and Johnson on the question of Vietnam, he once more insisted, recapitulating a perspective central to our study. Kennedy didnt want to be dumb, he said. Johnson didnt want to be a coward. Bundy was still struggling to understand the significance of the air-strike strategy he had advocated in the winter of 1965. What were its implications? Bundy asked aloud. Did it precipitate a chain of events that dramatically accelerated the Americanization of the war? He also revisited the failure of diplomacy in Vietnam, which he described as a delusion mistakenly embraced by opponents of the war. Why, Bundy now asked, didnt we settle the war at the negotiating table? He promptly answered his own question: After the American escalation of 1965, he declared, a diplomatic solution in Vietnam was simply not viable. On the question of Kennedy and Vietnam, Bundy instructed me to marshal the evidence once more and prepare an outline describing the choices Kennedy would have confronted in Vietnam had he lived to serve a second term. Clearly there was a great deal of work to be done to consolidate the rich but diffuse content of our collaboration.