To all those touched by the Vietnam War

Contents

T hey were not bad men. But they made some very bad decisions. Certainly, their decisions illustrate a disturbing disconnect between intent and effect, a chilling contrast not uncommon at the highest levels of governmentthen and now. There is overwhelming evidence that their decision-making was not always rational and logical. But people, as each of us knows deep down, are not always rational and logical. Mental mistakes are inherent in human nature. People have trouble seeing how their minds can mislead them. Our decision-making often has more to do with our desires than it does with reality. Yet the consequences are very real and, in the case of these men and those whose lives they affected, tragic.

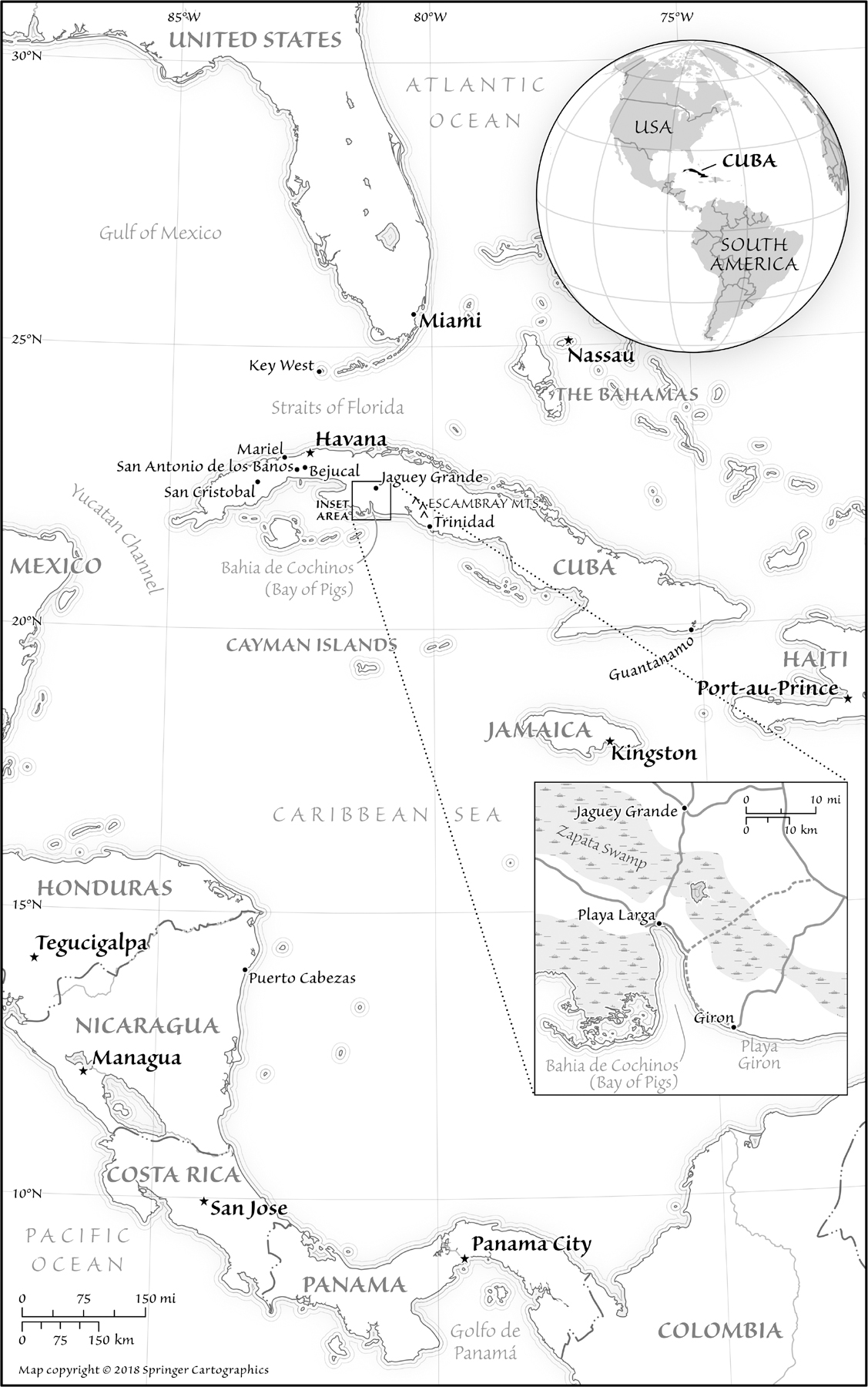

These were the men of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations who presided over the Bay of Pigs invasion, brought the United States to the brink of nuclear Armageddon during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and led the country into the quagmire of Vietnam. Extraordinarily bright and able, their judgments and decisions on Cuba and Vietnammore linked than commonly assumedmake them appear blind, slow, and altogether inadequate in dealing with problems that inflicted terrible suffering on millions of people. It is an unnerving puzzle: How and why did such intelligent and patriotic men not only make such unwise decisions but continue to make them despite circumstances and their previous professional accomplishments? What are the implications of their experience for the process of decision-making generally? These are the questions that drive the investigationa sort of detective storyat the heart of this book.

Their example exposes the limitations of the rational actor model of decision-making, which assumes that decision-makers take account of available information, potential costs, and benefits in defining options, and act consistently in choosing the best course of action. Arrogance and ignorance help explain their mistakes, to be sure, but their failure goes deeper, and has more relevance, than that. Only by drawing upon recent findings of psychologists, cognitive scientists, and behavioral economists can we gain a more complete sense of what went wrong. This research sheds considerable light on the errors that people make in judgment and choice, showing how the cognitive constraints of decision-makers, combined with the complexity of their tasks, undermine their capacity to navigate toward a more objective assessment of reality. Such shortcomings, as Nobel Prizewinning psychologist Daniel Kahneman of Princeton University and the late Amos Tversky of Stanford University observed, are too widespread to be ignored [and] too systematic to be dismissed as random error. Simon labeled this bounded rationality. An analytical approach based on an understanding of these flaws inherent in human decision-making does not excuse the serious mistakes that Kennedys and Johnsons men made, but it does make them comprehensible and coherent, accounting more fully for why they made the mistakes they did, and why they so often repeated the same errors despite manifestly unfavorable results.

In this light, we can see that their story is not a simple cautionary tale of hubris. It is the more complex and sobering tale of well-intentioned individuals making bad decisions. The pages that follow help us better understand both why good people sometimes make decisions that lead to big trouble and what happens when they begin to lose control of events. Such dynamics, if we are honest with ourselves, can apply to anyone. We all know people who continue to make foolish decisions in the face of bad consequences. The reason is that more oftenand in more ways than we like to admitpeople rely on things other than available information and logic to make decisions. Even the best minds are prone to such errors. Highly intelligent and accomplished people, when dealing with complex problems under stressful conditions, are no less immune to cognitive foibles than are we in our own lives. We are, concludes Daniel Kahneman, prone to overestimate how much we understand about the world. They certainly were.

Deep down, we know that each human being can err, inflicting suffering and themselves suffering in turnthe pain of the world. But error and suffering have their purpose if they can help others gain insights into the glitches of human nature and profit from those insights. The ancient Greeks called this pathei mathos, learning by suffering. Perhaps the best place to begin solving the puzzle of good intent producing disaster is by looking at the story of Robert McNamara.

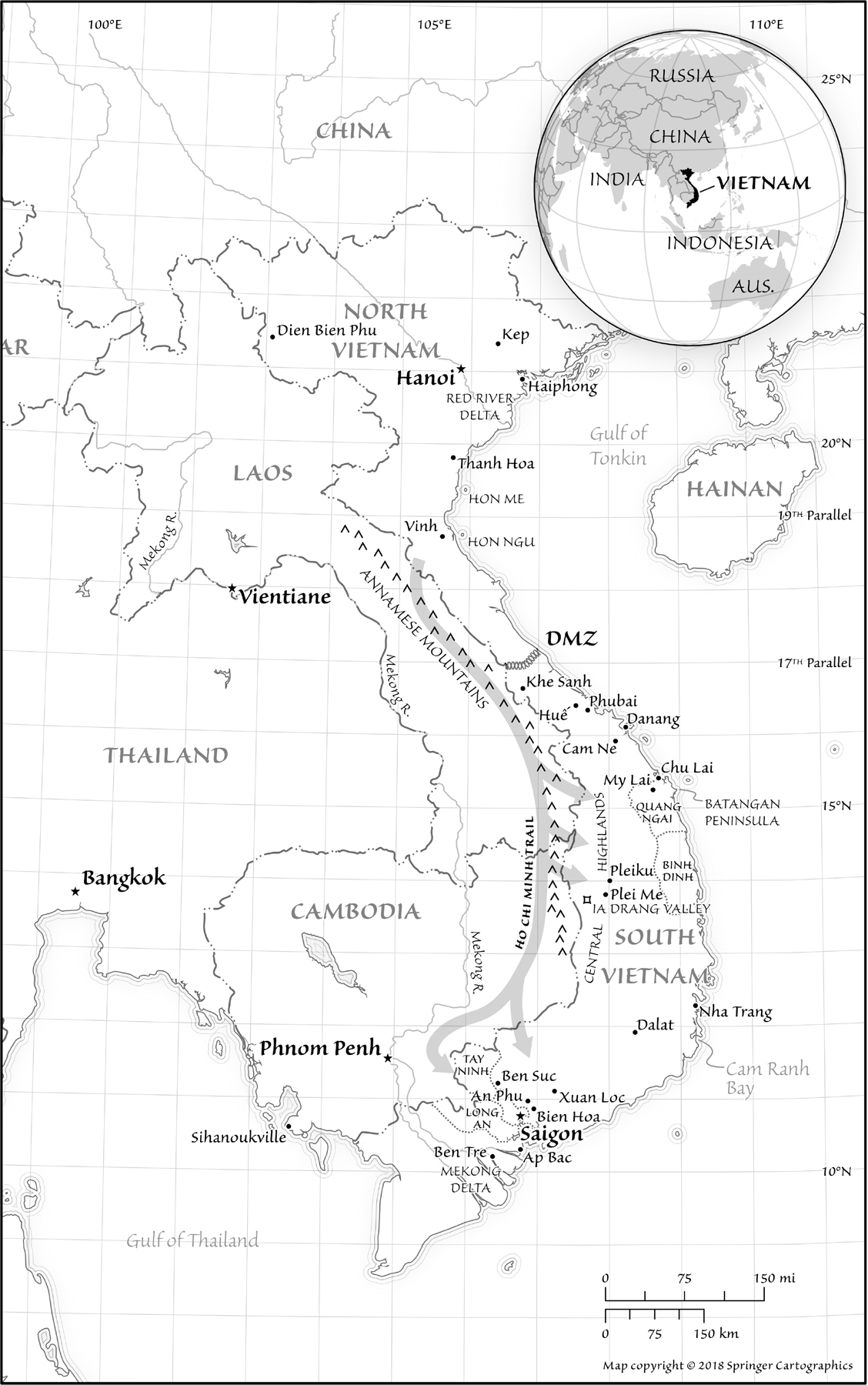

Robert McNamara spent decades running away from Vietnam. The longest continually serving secretary of defense in American history (from January 1961 through February 1968), McNamara led the Pentagon with more force and vision than anyone before or after him. Under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson from 1961 to 1968, he became one of the chief architects of the Vietnam War, the most divisive conflict in twentieth-century American history. For a generation of Americans, Vietnam became known as McNamaras War and McNamara became the face and living symbol of a struggle fought half a world away in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Eventually Americans of all ages and political persuasions associated him with what went wrong in Vietnamand a great deal went wrong: the conflict led to the death and wounding of millions of Indochinese and hundreds of thousands of Americans; damaged American prestige; exposed the limits of American virtue, wisdom, and power; poisoned and polarized American politics; and deeply and lastingly divided the American people. It inflicted a lingering toll of incalculable anguish and hurtphysical and emotionalon countless people in the United States and Southeast Asia. For many of these people, the suffering has never endedin fact, can never end.

The singling out of McNamara for blame and condemnation, regardless of the contribution of others, was a powerful and understandable reaction deeply rooted in human experience. More than twenty-five hundred years ago in ancient Greece, a cripple or beggar or criminal was stoned, beaten, and cast out of the community in response to a natural disaster such as a plague or famine. In ancient Israel on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement and the holiest day of the year for Jewish people, the High Priest ascended the Temple Mount and ritually slaughtered a goat as an offering to the Lord. The High Priest then laid his hands on a second goat, confessed the sins of the people of Israel, and sent the goat off to the wilderness. To ensure it never returned, the goat was led to a cliff outside the city walls of Jerusalem and thrown over the precipice. In the aftermath of Vietnam, Americans sought someone on whom to focus their anger and rage at the sins inflicted and endured as a result of the war. Antiwar protestors and Vietnam veterans often shared nothing in commonexcept this: they wanted, even needed, to find psychological relief for their fury and enduring suffering. They found it by vilifying Robert McNamara. The man with slicked-back hair and rimless glasses became a kind of toxic talisman. For many people, he still iseven almost a decade after his death and nearly half a century after the war ended.

This reaction to McNamara began early on. In 1965, the United States escalated its involvement in the war in order to avert the collapse of its South Vietnamese ally. That escalation boosted casualties of soldiers and innocents alike and increased physical destruction throughout Vietnam. Newspapers and televisions brought vivid images of death and devastation into Americas living rooms. Such images profoundly disturbed an intense, sensitive thirty-one-year-old Quaker husband and father from Baltimore named Norman Morrison. Deeply committed to Quaker principles of pacifism and personal witness, Morrison felt compelled to take an extreme, even desperate step. What can we do that we havent done? he asked his wife, Anne. The next day, November 2, 1965, he wrote her a note after she had gone to work. For weeks... I have been praying only that I be shown what I must do. This morning with no warning I was shown. At twilight that day, Morrison drove fifty miles from his home in Baltimore to the River Entrance of the Pentagon in Arlington, Virginia, and parked forty feet below the window of McNamaras office.