Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the Print Version

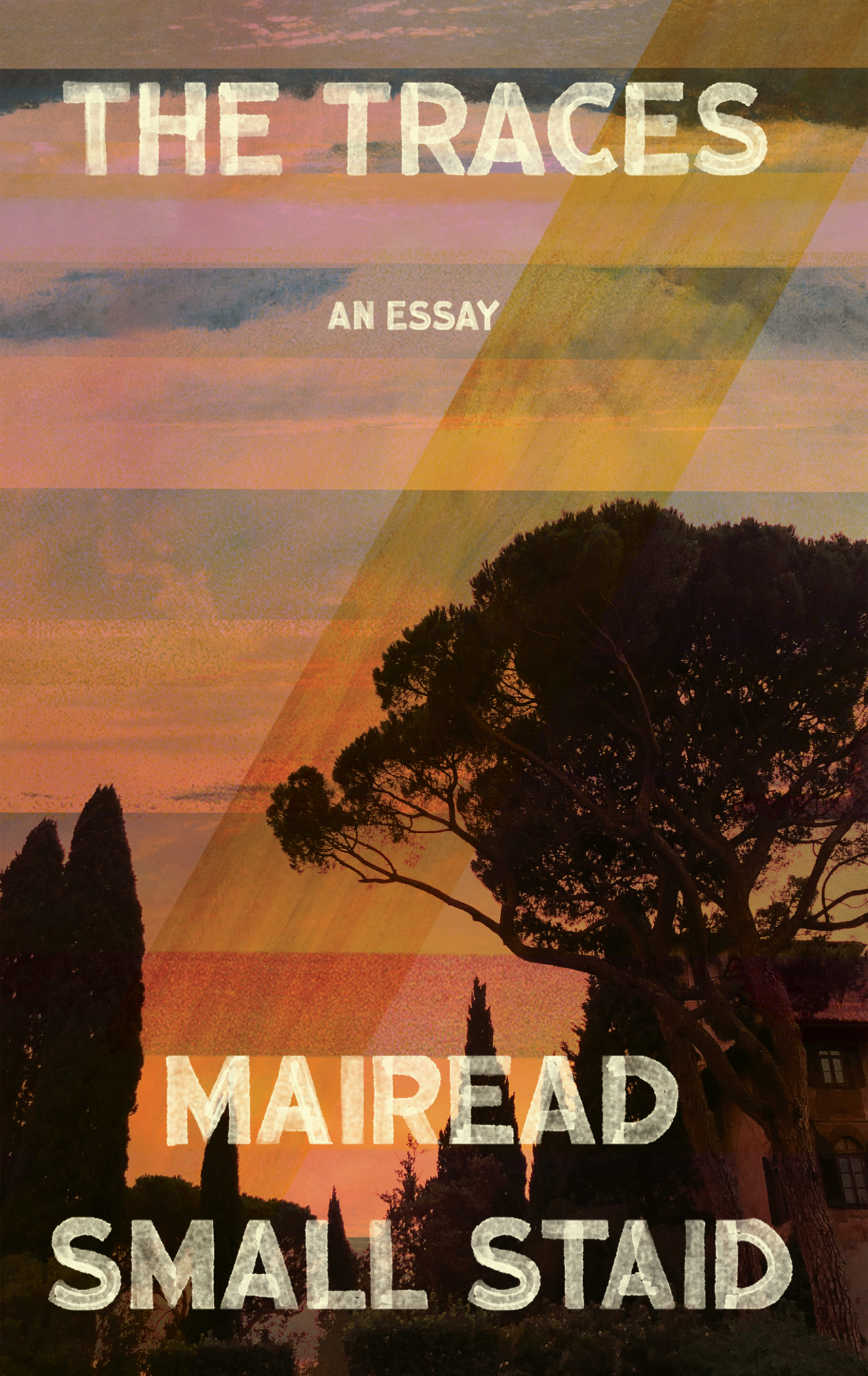

THE TRACES

AN ESSAY

Mairead Small Staid

Published by

A Strange Object, an imprint of Deep Vellum

Deep Vellum is a 501c3 nonprofit literary arts organization founded in 2013 with the mission to bring the world into conversation through literature.

Copyright 2022 Mairead Small Staid. All rights reserved.

Excerpts from Invisible Cities by Italo Calvino, translated by William Weaver. Copyright 1972 by Giulio Einaudi editore, s.p.a. Torino, English translation copyright 1983, 1984 by HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission of Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

This is a work of nonfiction, but memory is fallible and some names have been changed.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in context of reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging Number: 2022019611

ISBN 978-1-64605-200-4

ISBN 978-1-64605-201-1 (ebook)

Cover design by Kelly Winton

Interior design and layout by KGT

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

for my mother

for my father

No one, wise Kublai, knows better than you that the city must never be confused with the words that describe it.

Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities

CONTENTS

CITIES & MEMORY

YOU COULD SAY I missed a place. You could say I missed a time, or a place and time, or the person I was in that place and timeall of these sayings would be true. You could say I missed a particular season of a particular year when I lived in a city now thousands of miles away and many years ago. That distance widens by the hour, yet it amazes me that any time has passed at all. When I first learned to drive, I found it hard to keep my eyes on the road ahead instead of the rearview mirrorhow entrancing it was, to see the past moving away from me at such speed. The sky and trees and buildings disappearing, and time made visible, physical, a set of measurements arrayed on the dashboard. Even now, I glance upglance backmore often than I should, as if the road might turn to mist behind me if I dont keep an eye on it.

So I keep an eye on it.

In Italo Calvinos novel Invisible Cities, the explorer Marco Polo tells the emperor Kublai Khan about the many fantastical places hes seen: cities built of gemstones and illusions; cities sitting atop ladders and sunk into lakes; cities that disappear at sunset, remade each day. Through Polos stories, Khan learns the customs and curiosities of the vast territories he has conquered; he learns the shapes of rivers and hills in the farthest reaches of his empire. In seeking to know them better, however, the emperor comes to understand the lands he claims to own as forever unknowable.

Polo begins his first report: Leaving there and proceeding for three days toward the east, you reach Diomira. We are not told where there is. We dont know where were coming from, nor what weve left behind, what we might see in our rearview mirror, could we glance at it. We begin in unknowing. Polo is less concerned with the past, whether of the city or the visitor to it, than with the interaction between the two at the moment of arrival. He speaks in the present tense.

One of the cities Polo has visited, however, is built by such backward-glancing, consisting solely of relationships between the measurements of its space and the events of its past. But what does the traveler know of that past? The city does not tell its past, but contains it like the lines of a hand. And the traveler takes that hand, shakes it in greeting, feeling the contours of the palm without knowing what they mean.

The city I visit is built of marble and limestone, water and air. Florences past began under Roman rule, a military outpost of the sprawling empire. The city became a city-state, transforming time and time again under the sway of Romans, Ghibellines, Guelphs, the Medici, Savonarola, Machiavelli, the Medici again. In the midst of these shifting arbiters, the Renaissance rose and crested and fell awaythough it lingers here, porous as yesterday. It lives on in the art and books, in the museums and classrooms, in the massive constructions of math and stone I pass by every day: the Duomo, San Lorenzo, Santo Spirito. The Renaissance built the Florence found in my books and continues to build the city; its the reason, after all, for my presence heremy footprints on the ghost of the Cassian Way, my own brief leavings.

I attend an American school on the southern side of Piazza Savonarola, the square named for a man who burned the books I love and was burned in turn. Inside, classrooms surround a green and flowering courtyard where I eat thin panini for lunch and drink espresso between classes, where I smoke cigarettes Ive rolled myself, tobacco being cheaper by the bag and the satisfaction greater, I find, when inhaling something my own hands have made. Though I speak Italian with my host family, most of my classes are in English. I read Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch in translation, taught by a tall British woman who smokes copiously, leaning alone and elegant against the courtyard walls. My seminar on Leonardo da Vinci is led by a vigorous American expat, his face creased and tanned from decades spent under this countrys sun.

I live a few blocks from school in an apartment with high ceilings and hardwood floors and my host parents: Mamma is a head shorter than I am, whip-thin, and skeptical; Babbo is tall, round-shouldered, and easily given over to laughter. It seems strange, at first, to call people who are not my parents Mom and Dad, even in another language, but I soon get used to it. Im a child, after all, stumbling over simple words. Im a child, being fed. Each morning, I wake to crisp biscuits and Nutella on the table, coffee and water ready to boil on the stoveall I need to do is turn the knob. Each night, I eat pasta and vegetables and meat dripping in sauces I cant name and will never taste again. Even as we eat lunch, my friend Annie and I have lengthy, longing conversations about what our host parents cooked the night before, what they might make next. We eat like crazy and are never sated. We swim through the days like catfish, taste buds covering our skin.

You can wonder about or if or whether, or you can simply wonder at. You can be full of wonder, the word turning from verb to noun, from action to state: a way of being. In Italy, I mostly do the latter. I stand before faades and frescoes with my chin uplifted, my notebook out. I write down facts and dates and anecdotes; I write down joy and want. I wonder at my own wonder. At my own happiness, which is near constantI wonder at this constancy. (I do not wonder about, or if, or whether it will last.) I spend a single fall in Florence and will spend too many years to come attempting to reckon with those months. But what is there to reckon with? They happened; theythat is, the I who lived within themhappen no longer. This is how time works, a series of selves stitched together. Oh my god, I said to friends, upon returning, it was the best time of my life.