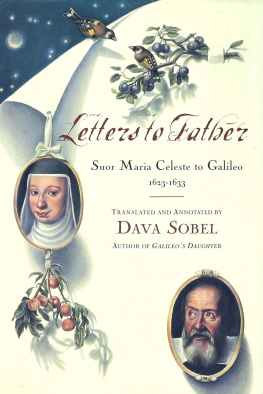

Copyright 2001 by Dava Sobel

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 2001 by

Walker Publishing Company, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Galilei, Maria Celeste, 1600-1634

[Correspondence. English & Italian.]

Letters to father: suor Maria Celeste to Galileo, 1623-1633 / translated and annotated by Dava Sobel.

p. cm.

English and Italian.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71807-5

1. Galilei, Galileo, 1564-1642Correspondence. 2. Galilei, Maria Celeste, 1600-1634Correspondence. 3. AstronomerItalyBiography. I. Sobel, Dava. II. Title.

QB36.G2 A4 2001

520'.92--dc21

[B]

2001026572

Book design and composition by Mspaceny/Maura Fadden Rosenthal

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

T he young woman who wrote these letters led a cloistered life in a gilded age. Virginia Galilei, or Suor Maria Celeste as she signs herself here, entered a convent near Florence at the age of thirteen and spent the rest of her days within its walls. Although she devoted most of her time to prayer, she served as the convent's apothecary, tended the sick nuns in the infirmary, supervised the choir, taught the novices to sing Gregorian chant composed letters of official business for the mother abbess, wrote plays, and also performed in them. She saw as well to many personal needs of her famous father, Galileo Galilei, from mending his shirts to preparing the pastries and candies he loved to eat. When he stood trial in Rome for the crime of heresy, she managed his household affairs during the year of his absence, sending him lengthy, detailed reports at least once a week.

Had she not been Galileo's daughter, her correspondence surely would have disappeared in the lapse of centuries. But because he saved her letters, brushing them with his importance, they endure to repeat their evocative story, still speaking in the present tense, suspended in the urgency of their once current affairs.

The 124 letters span a decade, from 1623 to 1633. In that period, a pope came to power who battled the Protestant Reformation and filled Rome with artistic monuments. The Thirty Years' War embroiled all of Europe and Scandinavia. The bubonic plague erupted from Germany into Italy, where it ravaged the city of Florence until stemmed by a miracle. And a new philosophy of science threatened to overturn the order of the universe. Suor Maria Celeste's evocative letters touch on all of these situations, but they dwell in the small details of everyday life. They tell who is sick, who has died, and who is getting well. They solicit herbs and fruits, fabric and thread. They beg for alms. They offer services, love, advice. They pray to the Lord for various blessings.

Except for the time Suor Maria Celeste chides Galileo for forgetting to send the telescope he promised, she does not discuss astronomy or physics. Her letters show she follows his studies by reading his books and asking him to describe what he is working on now. More important, the letters expose a relationship that redefines Galileo's character. Through them, the legend of a brilliant innovator becomes someone's loving father; the man generally thought to have defied the Catholic Church is seen to depend on the prayers of a pious daughter.

Suor Maria Celeste probably wrote Galileo many more than just these 124 letters, as she was already twenty-two years old by the date of the first in the series. Nor is there anything in that first letter of May 10, 1623, to suggest that it initiates their epistolary relationship. Another obvious gap occurs in the year 1624, which is represented by a single letter, dated April 26, just after Galileo set off at the height of his power to visit the new pope.

"What great happiness was delivered here, Sire, along with the news of the safe progress of your journey as far as Acquasparta," this one begins, "and we hope to have even greater occasion for rejoicing when we hear tell of your arrival in Rome, where persons of grand stature most eagerly await you." Galileo stayed in Rome through early June. No doubt the long separation occasioned a stream of news to pass back and forth in writing, of which no trace remains. But it is the nature of letters to go astray. At least an appreciable sample of Suor Maria Celeste's correspondence survives. Galileo's replies, on the other hand, have disappeared.

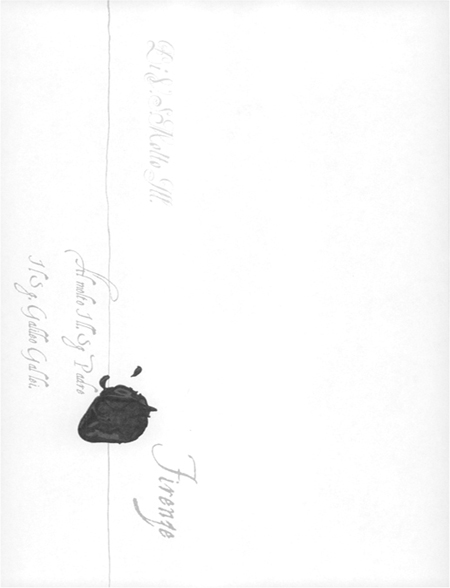

"I set aside and save all the letters that you write me daily, Sire," Suor Maria Celeste wrote on August 13, 1623, "and whenever I find myself free, then with the greatest pleasure I reread them yet again, so that I abandon myself to thoughts of you." His half of their dialogue thus vanished through no fault of hers. Someone else must have lost or destroyed Galileo's letters.

Little is known of Suor Maria Celeste beyond what she says herself in these letters. Her birth in Padua on August 13, 1600, was recorded in a baptismal notice dated the twenty-first of that month. The announcement named her mother, "Marina of Venice," but not her father. Although Galileo and Marina Gamba never married, their twelve-year union produced a second daughter in 1601 and a son in 1606.

As a child, Virginia lived in Padua with her mother and siblings, a short walk away from the house Galileo shared with his artisans and resident students. She may have attended school, though there is no record of her having done so. Possibly she acquired her perfect grammar and literary grace from her father, who is considered a giant of Italian prose. Her mother belonged to an undistinguished family and probably never learned to read or write. But Grandmother Giulia Ammannati Galilei had gone to school as a girl in Pisa, and when Giulia took the nine-year-old Virginia home to stay with her in Florence, she may have tutored her in rhetoric.

Soon after Virginia turned ten, Galileo became philosopher and mathematician to the grand duke of Tuscany, which enabled him to move to Florence. He brought Virginia's younger sister, Livia, along with him, and father and daughters lived a while in the grandmother's lodgings. He had left the boy, Vincenzio, back in Padua, since he was only four and therefore too young to leave his mother. Galileo sent money to Marina, and kept on cordial terms with the man she ultimately married. In time he sent for Vincenzio, had him legitimized by the grand duke, and enrolled him in the University of Pisa to study law.

Galileo's decision to cloister his daughters made sense in seventeenth-century Italy. Girls from good families either got married or entered one of dozens of convents in every city. In Florence alone, fifty-three convents promised refuge and employment to girls who could not arrange a marriage, or whose families could not afford to pay dowries for every daughter. Some number of the city's four thousand nuns must have felt a true religious calling; others actively sought the cloistered life for the opportunities it offered in playwriting, poetry, and musical composition, which struck some young women as preferable to the burden of marriage and the danger of childbirth. No one knows how many girls chose the convent of their own free will, and how many pursued a "forced vocation" at their parents' insistence. Either way, a nun's work held honor and value in society. During the plague, for instance, Suor Maria Celeste's convent was enjoined by the Florentine Magistracy of Public Health to keep a constant prayer vigil that would help drive the pestilence out of the city.