Pagebreaks of the print version

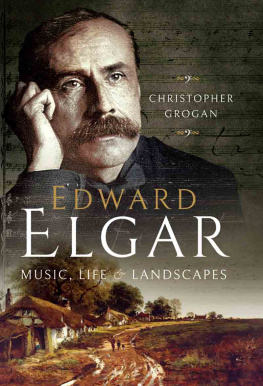

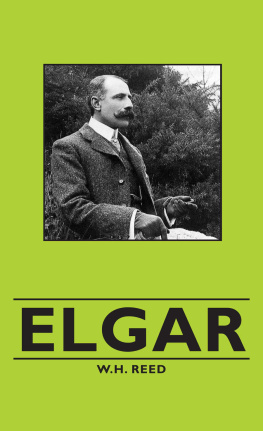

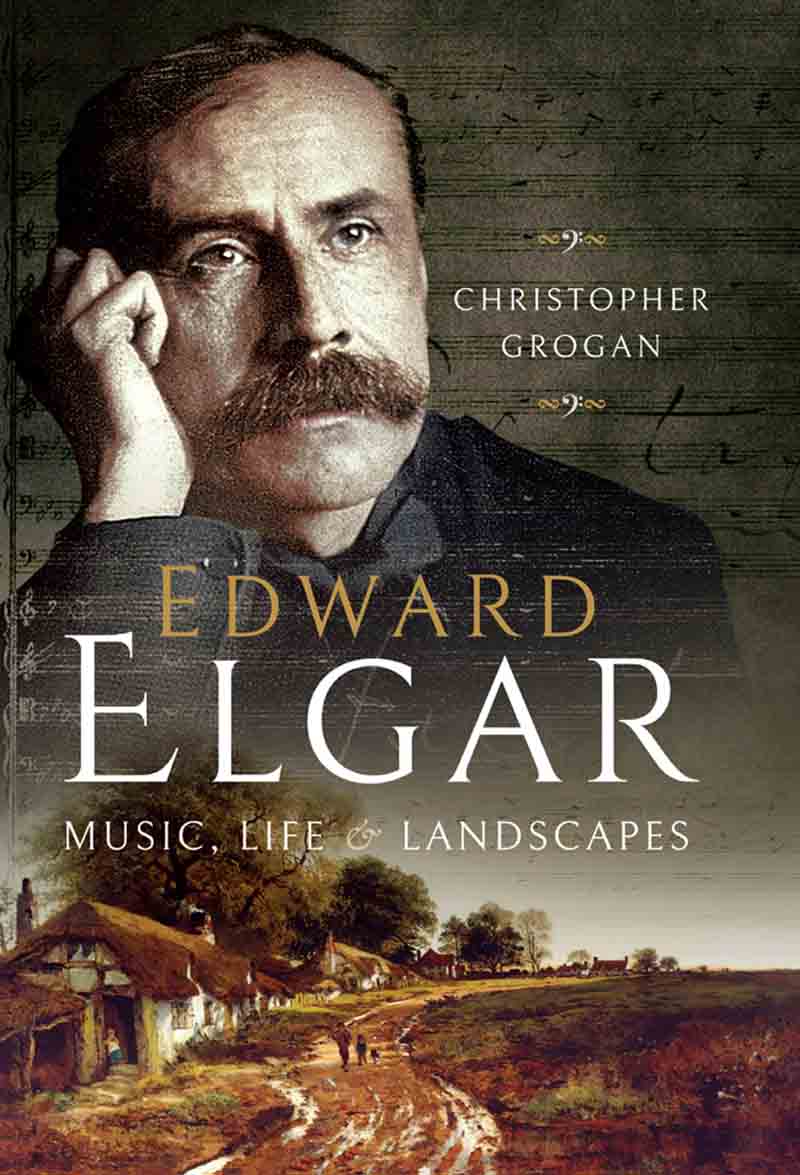

EDWARD ELGAR

EDWARD ELGAR

MUSIC, LIFE AND LANDSCAPE

CHRISTOPHER GROGAN

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire - Philadelphia

Copyright Christopher Grogan, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52676 462 1

ePUB ISBN 978 1 52676 463 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52676 464 5

The right of Christopher Grogan to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

To the memory of my friend Paul Manderson

19632015

and our walks on the Malvern Hills in the

Elgarian summer of 1984

Acknowledgements

My introduction to the music of Edward Elgar occurred in the auspicious year 1984, when national celebrations were in train to mark fifty years since the composers death and Jerrold Northrop Moores magisterial biography Edward Elgar: A Creative Life had recently appeared. Amanda Ballard, a fellow music student at Royal Holloway College, invited me to Worcester for the duration of the Three Choirs Festival. The Apostles and The Kingdom were performed consecutively that year and made a deep and lasting impression; the opening of the Prelude to the latter work struck me then, as it does now, as one of the most thrilling things in music. I was grateful to Amanda then for what was a life-enhancing experience, and remain very much so now.

In that summer, I was on the verge of choosing a subject for my PhD and settled on a detailed, sketch-based, study of Elgars creative process in The Apostles . My guide through the next four years was Robert Anderson, a wise and generous Elgar scholar and prominent Egyptologist. Robert was a keen, but hardly uncritical, Elgarian and we spent many afternoons at his house in Kensington arguing the merits of this or that work. His influence on my dissertation and on my thought more generally was profound, and I am grateful that his spirit hovers over much of what follows.

Looking back from 2020, it is apparent, nevertheless, that my PhD was written during the Dark Ages of Elgar scholarship, when most writing about the composer was concerned either with delving into odd corners of his life, or with the running to ground of uncatchable Elgarian enigmas. Scholarly exegesis was rare and Elgar was generally not considered a suitable subject for academic study. Since the turn of the millennium, however, this situation has undergone a happy transformation and Elgars works have come under the spotlight of new and varied critical and analytical disciplines. The effect on the composers reputation has been entirely positive and has helped him regain, in part at least, the reputation he held, prior to the First World War, as a progressive, internationalist late Romantic composer, the equal at least of his contemporaries Strauss and Mahler. This book is hugely indebted to the flourishing of new scholarship, and I must mention with gratitude the following names in particular whose work has informed my own: Byron Adams; Michael Allis; Tim Barringer; David Cannadine; John Drysdale; Nalini Ghuman; Corissa Gould; Daniel M. Grimley; J.P.E. Harper-Scott, James Hepokoski; Charles McGuire; Matthew Riley; Julian Rushton; Benedict Taylor; and Aidan J. Thomson.

Much of this book was written in snatched hours in the Ipswich County Public Library and, at a time when this nationally invaluable resource is under huge threat (nearly 800 public libraries have closed since 2010), it is important to record my appreciation to the staff at Ipswich for providing me with such a conducive environment for writing. My wife Katherine and children Lucy, Hannah and Ben have been endlessly supportive during the months when my attention has been distracted, and I am very grateful to them for their understanding and patience. My brother Adam has offered quiet days in his cottage in Sussex, and Rachel Barbour has read and commented insightfully on several chapters; I am indebted to both. I am also deeply grateful to the NHS staff at Ipswich Hospital, without whose swift actions in January 2020 this book would definitely not have been completed. Finally, I must thank my collaborator (and sister-in-law) Suzie Grogan, who initiated the project, provided me with background materials, proof-read the entire text, helped source many of the images and liaised with editors Heather Williams, Carol Trow and all the team at Pen and Sword Books, to whom I am also grateful.

Christopher Grogan

Suffolk, 31 January 2020

Prelude

he has that peculiar kind of beauty which gives us, his countrymen, a sense of something familiar the intimate and personal beauty of our own fields and lanes When hearing such music as this we are no longer critical or analytical, but passively receptive. It falls to the lot of very few composers, and to them not often, to achieve this bond of unity with their countrymen.

When Elgars Cello Concerto reached my young ears fifty years ago across the seas, it transfixed me with its power to project a landscape I did not know. When knowledge came of Worcestershire, Elgars projection proved strangely accurate. How could music do that?

I still remember the first time I heard [Elgars Violin Concerto] and how much it reminded me of the landscape, the colour, the image of England. It is always very emotional for me to perform this piece as all the precious memories of my time in England come flooding back.

As these three diverse quotations amply illustrate, Edward Elgars music has, since his death in 1934, become inextricably linked to an enduring popular cultural vision of the English rural landscape and in particular that of the Malvern Hills and the borderlands of Worcestershire and Herefordshire.

Although he never incorporated an English folk tune into his music (indeed, he disliked the practice and memorably asserted that I write the folk songs of this country), did not employ the imitative techniques of nature painting used by some of his contemporaries and rarely gave his music topographically precise titles derived from English place-names, his distinctive sound world has become deeply associated with (and has been appropriated by advocates and promoters of) a pastoral idyll that, although highly selective and idealistic, is now a touchstone of cultural identity for the English. Of all British composers, he alone has achieved the status of an icon of locality;