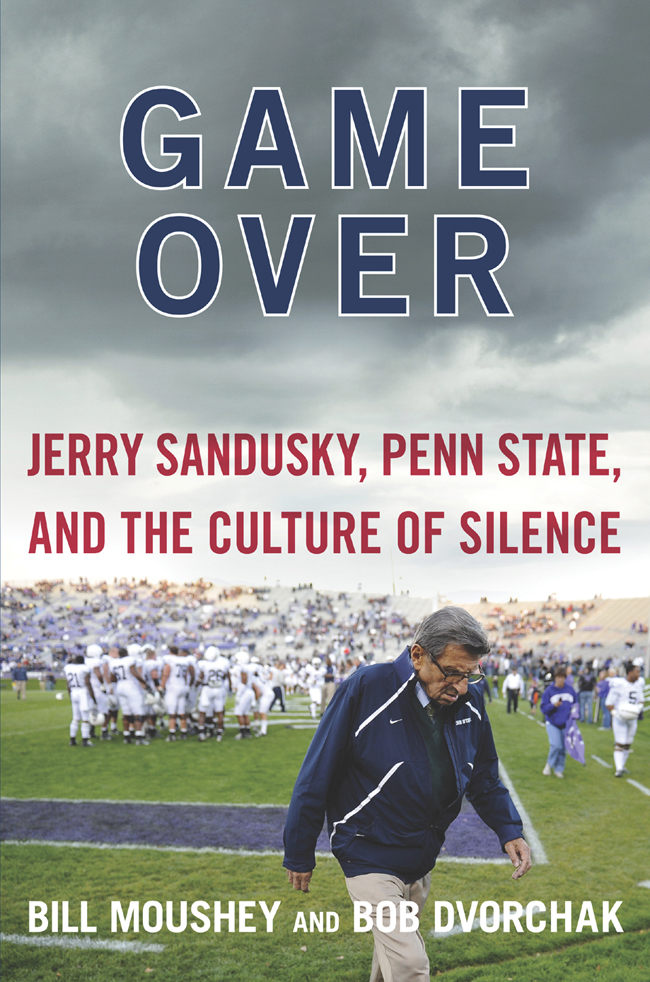

GAME OVER

JERRY SANDUSKY, PENN STATE, AND

THE CULTURE OF SILENCE

Bill Moushey and Bob Dvorchak

Dedicated to the young men and their advocates who had the courage to speak out and who now know that they are not alone

Contents

T he journey to Penn State University is challenging even when the weather is ideal. The drive from Philadelphia, two hundred miles to the east, or from Pittsburgh, a hundred fifty miles west, takes three hours and requires the crossing of mountain ridges and rivers to reach a campus situated in the middle of the state and seemingly in the middle of nowhere. The trip was even more arduous for Penn State football fans traveling there on October 29, 2011, because of a surprise snowstorm pummeling the northeast from Washington, D.C., to Maine. But this was a football Saturday tinged with history. Pilgrims making the trek to the game shared the roads with snowplows and salt trucks while keeping tabs on weather advisories. University officials alerted fans about the closure of grass-lot parking areas and scrambled to make shuttle buses available to service paved lots too far away to slog through six inches of snow to Beaver Stadium, where a 3:30 kickoff was scheduled.

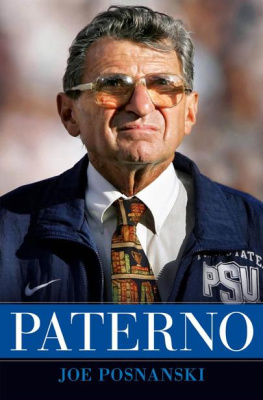

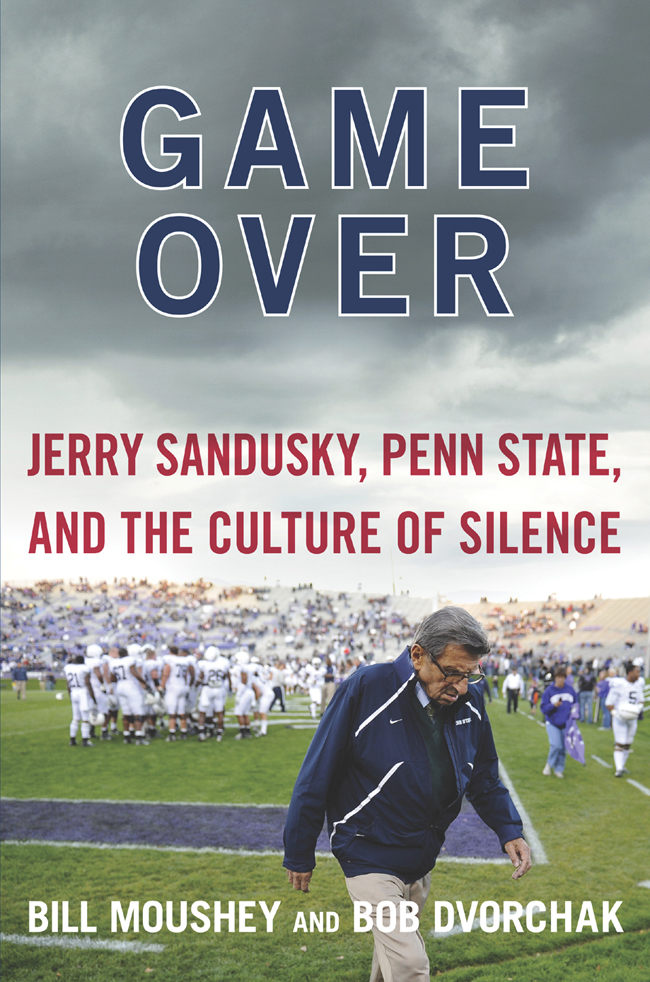

Despite the headaches posed by the weather, the fans arriving in Happy Valley, the nickname of the idyllic setting surrounding the town of State College, Pennsylvania, were in a festive mood. Coach Joe Paterno, a man revered by the Penn State faithful, was one game away from the 409th win of his career. A victory over Illinois, the opponent that day, would distinguish him as the winningest coach in the history of Division I college football.

Sixty-one years had passed since Paterno, an octogenarian, first set foot on campus in 1950, two years after Penn State played its last season in leather helmets. An outsider at first, the Brooklyn-born Paterno arrived as an assistant coach under Charles Rip Engle, who came to Penn State after coaching Paterno as a quarterback and defensive back at Brown University.

At Brown, Paterno majored in English literature and took courses preparing him for law school. With his thick-rimmed black glasses, he looked more like a professor than a play-caller. He was fond of quoting the English poet Robert Browning: A mans reach should exceed his grasp, or whats a heaven for? But football was in his blood, and he set down roots after falling in love with Penn State. When Engle retired in 1966, Paterno took over with an ambitious plan to make Penn State a football powerhouse by stressing academics and athletics. His blueprint came to be known as the Grand Experiment.

Forty-six years after his first win in his first game, Paterno had become the face of Penn State. No other coach had built such all-encompassing power at one school and kept it for so long. No other coach had more winning seasons, more postseason appearances, and more bowl victories.

JoePa, as he was affectionately called, was already enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame in South Bend, Indiana. Winning so much for so long made him seem larger than life, larger than the seven-foot-tall statue of him outside the universitys football stadium. The monument includes his words: They ask me what Id like written about me when Im gone. I hope they write I made Penn State a better place, not just that I was a good football coach.

Paternos success had enriched the school as well. The coach had grown Penn States football program into a moneymaker that turned a profit of $53 million a year, the third-largest moneymaking machine in college sports. The profits were enough to finance every other sports program at the university. Penn States endowment was flush with cash from alumni donations, corporate sponsorships, and TV revenue. Beyond that, Paterno and his wife, Suzanne, a Penn State grad who majored in English literature and the matriarch of what she called the Penn State family, had donated $4 million of their own money and helped raise $13.5 million more to fund a five-story expansion of the main library on campus. Suzanne had a legacy of her own: her name adorns the Suzanne Pohland Paterno Catholic Student Faith Center at the center of campus. Penn State may be the only university in the country where the library is named after the football coach and the football stadium is named after a former administrator. It made perfect sense at Penn State.

Approaching State College from any direction, one can see Beaver Stadium, a massive, imposing monolith as recognizable as Mount Nittany, the landmark geographic feature that dominates Happy Valley. With a capacity of 106,572, it is twice as large as the new Yankee Stadium in New York. In fact, it is the second-largest stadium in the Western Hemisphere and the fourth largest in the world. During Paternos reign, the stadium was expanded six times and held double the number of fans from when he first became head coach. The latest expansion, completed in 2001 at a cost of $94 million, added 11,000 seats, including sixty high-end and enclosed skyboxes. The extra seats, however, caused some dismay for ticket buyers because new construction obscured the view of Mount Nittany for some inside the stadium.

Paterno and football were so popular that students arrived the night before a game, sometimes days before, to get in line for a crack at the choicest seats in the student section. These fanatics erected tents as shelter against the elements and unrolled sleeping bags on the concrete sidewalk outside the stadium. The encampment was called Paternoville, and students abided by rules of conduct established by the self-styled Paternoville Coordination Committee. To keep their spirits high, Coach Paterno was known to stop by with pizza from time to time. While the older alumni were more apt to bundle up in parkas and foul weather gear on a snowy Saturday, some occupants of Paternoville slathered their bare upper torsos with blue and white paint to show their team spirit, no matter how much discomfort they had to endure. Others donned Paterno masks to pay homage to the coach. Their wake-up call on this snowy Saturday was the whir of snowblowers clearing the playing field. Grounds crews equipped with snow shovels fought the battle in the seating areas.

Penn State players had a one-mile journey of their own to get to the stadium. They donned their uniforms at the Lasch Football Building, which houses the locker rooms and showers and adjoins the fields where the team practices during the week. Then they rode four blue university buses to the arena. Fans lining the route shouted encouragement and waved Penn State flags as the buses passed. At the main gate more fans formed a human tunnel, so the players made a heros entry through the cheering admirers and into the packed stadium.

Because of the snowstorm, only an estimated 62,000 zealots occupied the seats for the game against Illinois, which, like Penn State, competed in the Big Ten Conference. Conforming with pregame tradition, fans rose to sing the Penn State alma mater.

As the game got under way, Paterno watched the action from a glass-enclosed viewing box high above the field. No longer did he prowl the sidelines during games; he was limited by shoulder and hip injuries incurred when a player ran into him at a preseason practice the previous August. Assistant coaches on the sidelines were handling the nitty-gritty chores associated with running todays game, aided by direction from Paterno. One of those assistants, a State College native and former quarterback named Mike McQueary, relayed plays from Paterno transmitted into his headset and sent them into the offensive huddle.

Next page