Introduction

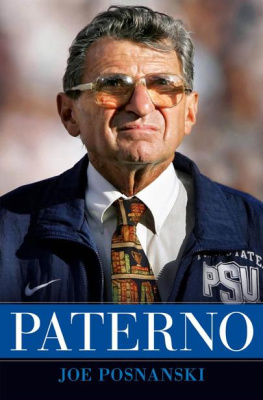

Several years after Id finished a 2004 book on the coach and his program, Joe Paterno asked a colleague what had become of me. Wheres the kid who wrote the book? he inquired. The kid was near 60 at the time. When you are, like Paterno, 84 and entering your 62 nd season on Penn States football staff, the world is full of kids. The winningest coach in big-time football history has outlived, outlasted, and outcoached all of his rivals, not to mention most of those who have chronicled his achievements.

Entering this 2011 season, his 46 th as the Nittany Lions head coach, Paternos familiar black mane is mostly gray. His gait has slowed, not by choice but because of injuries he suffered along the sideline and in practice. He has made some concessions to his staff but not to time. His active mind remains that of a young mans, even if his cranky impatience increasingly betrays his age.

He has won 401 football games at Penn State, including a record 24 bowls. He has had two national champions and five unbeaten seasons. What else is there? Why does he go on? When will he retire?

Those questions lurk behind any late-life examination of Paterno and his admirable legacy of triumph on and off the field. In his more than six decades, he has avoided even the hint of a major scandal, has graduated a disproportionately large percentage of his players, and has managed to fill enormous Beaver Stadium Saturday after Saturday. And whether or not you want to debate how much of the credit belongs to him, the only common denominator through those years of Penn State glory has been Paterno. Long past the age when others might have quit, content in their accomplishments, the idealistic Paterno soldiers on, convinced that he is fulfilling the fate life set before him.

He is, like Penn State football, veiled from too-close scrutinyby geography, inclination, and habit. In the authors note to the previous book, I began by pointing out how difficult it was to write about Paterno and Penn State football, [Its] a lot like being a linebacker defending against one of those sweeps his Nittany Lions love to run: Youve got to keep your head up at all times, fight off wave after wave of interference, and never take your eyes off the target, no matter how well-protected and untouchable he might seem. By attempting to do so again, I found a man and a story that are among the most remarkable in postWorld War II America.

With a better understanding of the Penn State football environment, by supplementing my earlier research and observation with additional reading, by frequent visits to the archives at a Penn State library that bears Paternos name, by new interviews and a reliance on decades of work by generations of my sportswriting colleagues, I hope Ive scraped away a few layers of Paternos famously tanned skin.

This project would have been inconceivable without all the books, magazines, newspapers, and documents listed in the bibliography. Particularly helpful were the oral-history materials gathered by Penn State historian Lou Prato and Altoona Mirror writers Neil Rudel and Cory Giger, and an earlier Paterno biography, No Ordinary Joe , by Michael OBrien. Wherever possible, I tried to use the fruits of my own research and interviews. But I depended often on comments he made to others over the yearsat news conferences, in private interviews, and during radio and TV broadcasts.

The result, I hope, is an entertaining narrative of Paternos life with an emphasis on those moments that helped transform this football coach from Brooklyn into a beloved and often misunderstood American icon.

Chapter 9

The official canonization of St. Joe took place in 1973. As a morally confused nation slipped out of Vietnam and stepped into Watergate, Paterno would earn his halo and ascend to the mountaintop of American heroes. Curiously, he would do so away from the football field, even though his Nittany Lions would go 120 that season.

The three events that marked his annus mirabilis seem almost Biblicala great temptation, a sermon on Mount Nittany, and a tearful, spiritual awakening in the heart of Babel.

Before 1973 was over, St. Joe would overshadow Paterno the coach. Thanks to the events of January 5, June 16, and December 13, his name and face would become symbols of steadfast virtue, not only in sports but in the rapidly changing world beyond. Paternos actions, words, and tears helped to counter a cynicism created by a self-destructing president, soaring oil prices, gasoline shortages, movie antiheroes, and baseballs designated hitter.

Penn States ultimate football success, when it came a decade later, would enhance his image and lay to rest whatever doubts remained about his abilities as a coach, a recruiter, and a leader. But football alone would no longer define him. From 1973 on, the first items on his resume would always be the virtues he showcased that year. They would be implanted so deeply in the public consciousness that they would endure no matter how many games he lost in the decades to come, no matter how many of his players got in trouble, and no matter how irritable or curmudgeonly he became.

On January 5, at a news conference in Rec Hall, Paterno announced that he was not leaving Penn State, ending both weeks of speculation and the single most transformative episode in his long career at the school.

It had begun innocently seven weeks earlier in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. On November 18, 1972, Penn State defeated Boston College 4526 for its ninth consecutive victory. As Paterno exited the Alumni Stadium field, well-wishers surrounded him. One was New England Patriots owner Billy Sullivan. The blunt and good-natured Irishman shook the Penn State coachs hand and then, eschewing any small talk, asked him if hed be interested in coaching his team.

His team, an original American Football League member for which Sullivan had paid $25,000 in 1959, needed help. Thirteen years old, having gone through the AFLs merger with the NFL and a recent change in its geographical surname from Boston to New England, the Patriots still had not won a championship.

In 1971, general manager Upton Bell, the son of the NFLs first commissioner, had wanted to replace Coach John Mazur with Paterno. Sullivan had hesitated then. Now, with Bell gone and the Pats headed toward a 311 finish, he could wait no longer.

A public-relations professional by trade, Sullivan saw in the Penn State coach an easy sell. From Sullivans perspective, the hiring would make good football and business sense. Though Paterno was the hottest coach in the college game, he was more than his record. His Ivy League background, his straightforward nature, his reputation as a reformer, and his intellectual bent all made him unique and extremely attractive to New Englanders.

Sullivan knew the Steelers and other NFL clubs had tried to lure Paterno in the past and failed. Somehow he was going to have to turn the coachs head.

With details of the just-completed game still swimming in his head, Paterno was polite but noncommittal with Sullivan at Boston College. A job change, he told the owner, wasnt something he could get his head around at that moment. But he promised to consider it.

The following Friday, as Paterno readied for bed and the next days season finale with Pitt, Sullivan phoned him at home. Joe, he said, what if you not only coach my team but own a piece of it, as well?

For Paterno, who had been courted before and would be again, the affair suddenly took on a whole new glow.

Just days after the Nittany Lions 92 regular season ended with a 4927 drubbing of Pitt, Paterno flew to New York to talk details with Sullivan. In addition to making him a minority owner in an NFL franchise, the four-year deal had a starting salary of $200,000, with guaranteed annual increases of at least $25,000. He would get two cars and between 3 and 6 percent of the team.

Next page