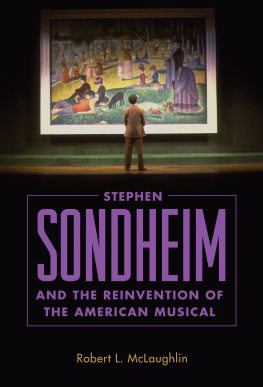

I always wanted to write about Stephen Sondheim. Actually, long before writing about him was a possibility, I just wanted to meet Stephen Sondheim. In the spring of that long-ago year 1977, my mother went to a benefit for the Phoenix Theatre, a repertory company that pioneered off-Broadway theater. The event included a performance of Side by Side by Sondheim, a revue of the composer-lyricists songs. Going to benefits was not the sort of thing my mother usually did, but my uncle was a playwright whom the Phoenix had championed, and he might have persuaded her. Sondheim at the time was exactly the sort of creator the Phoenix wanted to associate itself with. He was remaking the American musical in the same way the Phoenix was trying to remake the theatrical landscape.

In 1977, I was fifteen. As part of the benefit package, my mother came home with a two-record album of the show. It was signed by Hal Prince, the artistic director of the Phoenix, in Magic Marker, and below that was Sondheims signature, in a more delicate hand, his Ss like two treble clefs. I had never seen a signed book or album, hadnt even known people did that. On the album cover, Sondheim, in profilebearded, dark brow loweredglared off into space. Behind him hovered the logos for his many musicals: West Side Story, Gypsy, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Anyone Can Whistle, Do I Hear a Waltz?, Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, and Pacific Overtures. Nine amazing showsand he was still only in his mid-forties. His imposing body languagechin up, arms crossedseemed to promise more were on the way.

My family lived in a large Upper West Side apartment. My parents agreed on very little, and so many rooms had almost no furniture, but in our living room there stood a gorgeous walnut-paneled KLH Model Twenty-Plus stereo my mother had bought and my father had paid for. The fight over its price had exceeded the hi-fis top volume, but that had been many years before. By now it had settled into place along one wall, near the ornate fireplace with layers of landlord paint covering the plaster putti.

My father, a lawyer, would put Dave Brubecks Take Five, a favorite of his, on the spindle, slide the lever, and down the disc would drop with a click. Despite a warning in the stereo manual not to, if you pulled the throw-arm to the side, a record would play over and overand thats what my father did. He worked away on legal matters as the record spun around and around. He was the only one in the family who could whistle, and sometimes from the back of the apartment where my brothers and I dwelt, I could hear Brubeck and him in a duet.

In 1976, I bought a copy of A Chorus Line after seeing the musical. The show immediately spoke to methe harsh judging, the self-doubt, the final triumph. The songs were memorableI Hope I Get It, What I Did for Loveand I loved them. Soon my father was playing them, too. Back went the throw-arm, down plopped A Chorus Line on top of Brubeck. One! Singular sensation! He even whistled the songs.

Every once in a while, my motheror was it me?would put one of the two Side by Side by Sondheim records on the spindle and let it drop. Songs with names like You Must Meet My Wife, Being Alive, and Another Hundred People would play then in the living room, spinning on top of the gyrating pile. These were witty, intricate, self-conscious tunes that got at life not through the front door but through a side window in a way that was new to me.

... Another hundred people who got off of the plane

And are looking at us

who got off of the train.

I soon understood that Sondheims songs were special in ways those from A Chorus Line were not. True, they werent as easily singable and definitely not as whistleable. Nor did his characters sing to express overwhelming emotions or resolve simple doubts the way Cassie and Diana did in A Chorus Line. Instead, Sondheims characters were made of doubt, of missteps, of ambivalence. Marry me a little. Side by side... by side. This complexity extended to the music itself, which Sondheim filled with tricky rhythms and harmonic improbabilities. Soon the songs in A Chorus Line seemed overbright to me, trying too hard to win my affection.

The liner notes for Side by Side by Sondheim suggested that Company had not been a success at first in its London run in 1972 because it was too New York for Londoners, and added cleverly that the same had been true of the original Broadway show two years earlierthat it was, in fact, almost too New York for New Yorkers. The musical revolves around a quintet of couples trying to persuade their single friend Bobby to commit despite their own mixed feelings about marriage. That group of arch, insecure, promiscuous frenemiescould that have been life there then? Even in my mid-teens, I knew it was. Sondheims music captured perfectly the New York I grew up in, with its graffitied subways and pot-filled parties, its uncertain adults and its adult children. By comparison, A Chorus Line often felt to me like just an out-of-towners idea of Manhattan.

Over the next four decades, I never got over my sense of having a unique connection to Sondheim, that he was, in some way, writing to me. In high school, I was in a production of West Side Story (in a nonsinging part, luckily for the audience). In my late-teens, twenties, and thirties, I saw his shows whenever they were performedSweeney Todd and Passion, and revivals of Merrily We Roll Along and Company. My thirties also included a CD of Assassins that I listened to over and over. Through all those years, he was the only living show composer whose work I cared abouteven the only one I could name. But its also true that I did many other things. I went to college, graduated, went to work, met my wife, had two children, had a dog that grew old and died, became a writer and wrote two books as well as profiles of lots of people who did lots of remarkable thingsa chef, a neuroscientist, a curator, a pianist, a chess champion, an environmentalist, and a passel of novelists. Each interested me fiercely in turn. Otherwise I could not have written about them. Still, I never forgot Sondheim or the album with his gracile signature.

Then, in late 2016, I saw Sondheims name on a list of prospective profile subjects at the New Yorker, where I was now a staff writer. According to the memo, the composer and lyricist had a new musical coming out based on two moviesone from the 1960s, the other from the 70sby the surrealist director Luis Buuel. This sounded too good to be true. Company had marked the start of an amazing, nearly twenty-five-year run that included Follies, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd, through to Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, and Passion. But by the late 2000s, Sondheims productivity seemed to have diminished. He had spent years working on a musical titled, at various points, Gold!, Wise Guys, Bounce, and finally Road Show. The work, about a pair of con men brothers, had never achieved optimal form or made a Sondheim-level impression on audiencesand that had been nearly ten years ago. Silence since. It was fair to ask if Sondheim had finally lost his creative spark. He himself had said that composers always do their best work by fifty, and he, by then, was well into his eighties. In more recent years, so far as I knew, he had seemed to concern himself more with his legacyrevivals, retrospectives, and tributesthan with new shows.

To write a musical based on The Exterminating Angel