Praise for Steve Reich

Mr. Reich has been a potent, and a very serious, force for change...among the great composers of the century.

Richard Taruskin, New York Times

Theres just a handful of living composers who can legitimately claim to have altered the direction of musical history and Steve Reich is one of them.

Andrew Clements, The Guardian

The greatness of Steve Reich is a given. His reputation as a prime originator in contemporary music is more or less etched in stone.

Alex Ross, liner notes to Phases: A Nonesuch Retrospective

Reich was intent on restoring the pleasure principle to contemporary music... He didnt reinvent the wheel so much as he showed us a new way to ride.

John Adams, composer

Saw this performed live in downtown New York in the late 70s... The music...floored me. Astonishing.

David Bowie, Vanity Fair , on Music for 18 Musicians

His music has become part of the common culture.

Los Angeles Times

Americas greatest living composer.

Village Voice

Steve Reich has influenced composers and musicians all over the world. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music for Double Sextet in 2009 and Grammy Awards for Different Trains (1989) and Music for 18 Musicians (1998). He received the Praemium Imperiale in Tokyo, the Polar Music Prize in Stockholm, the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale and the Gold Medal in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He has been named Commandeur de lOrdre des Arts et des Lettres in France and has been awarded honorary doctorates by the Royal College of Music in London, the Juilliard School in New York and the Liszt Academy in Budapest, among others.

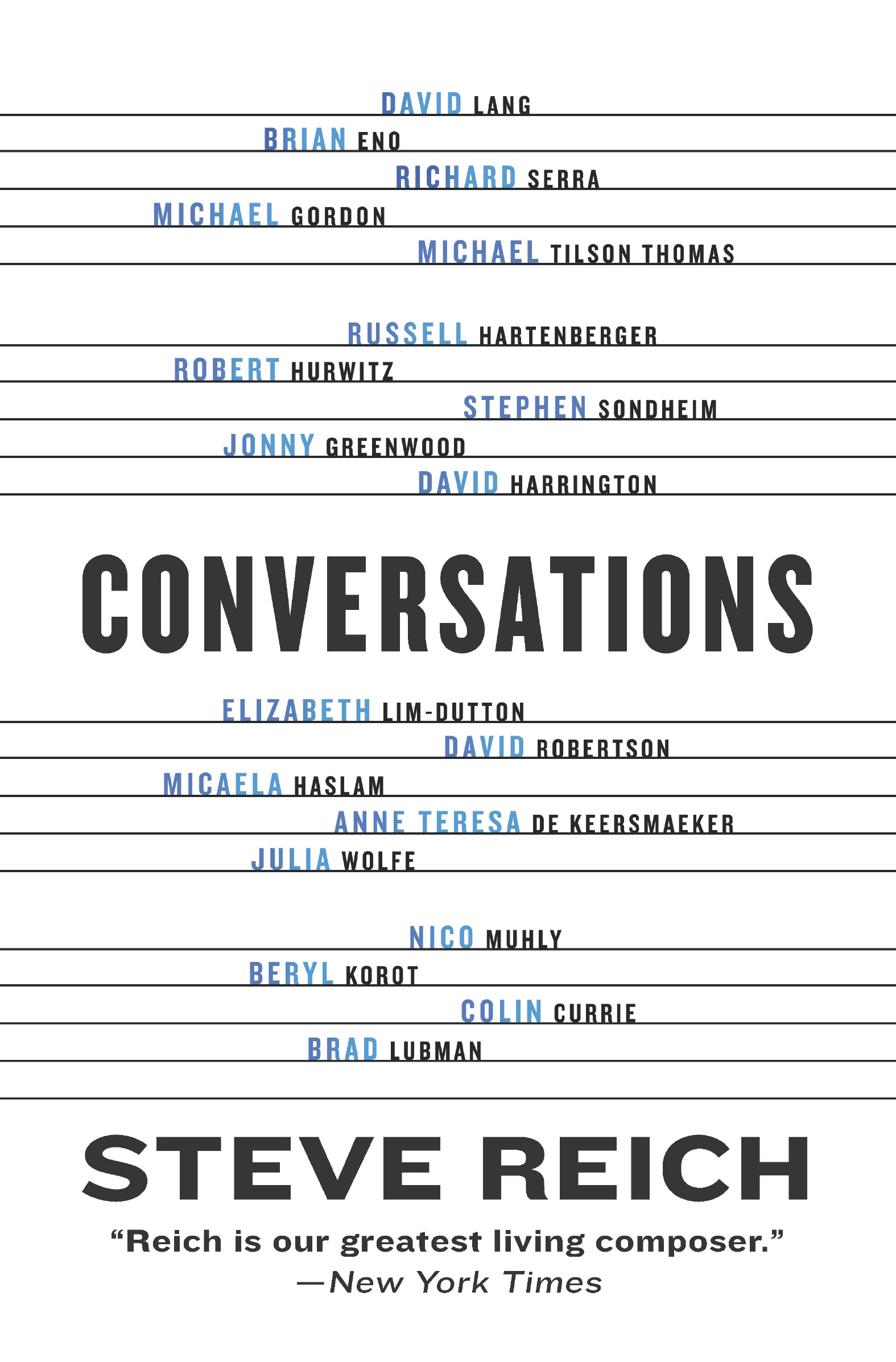

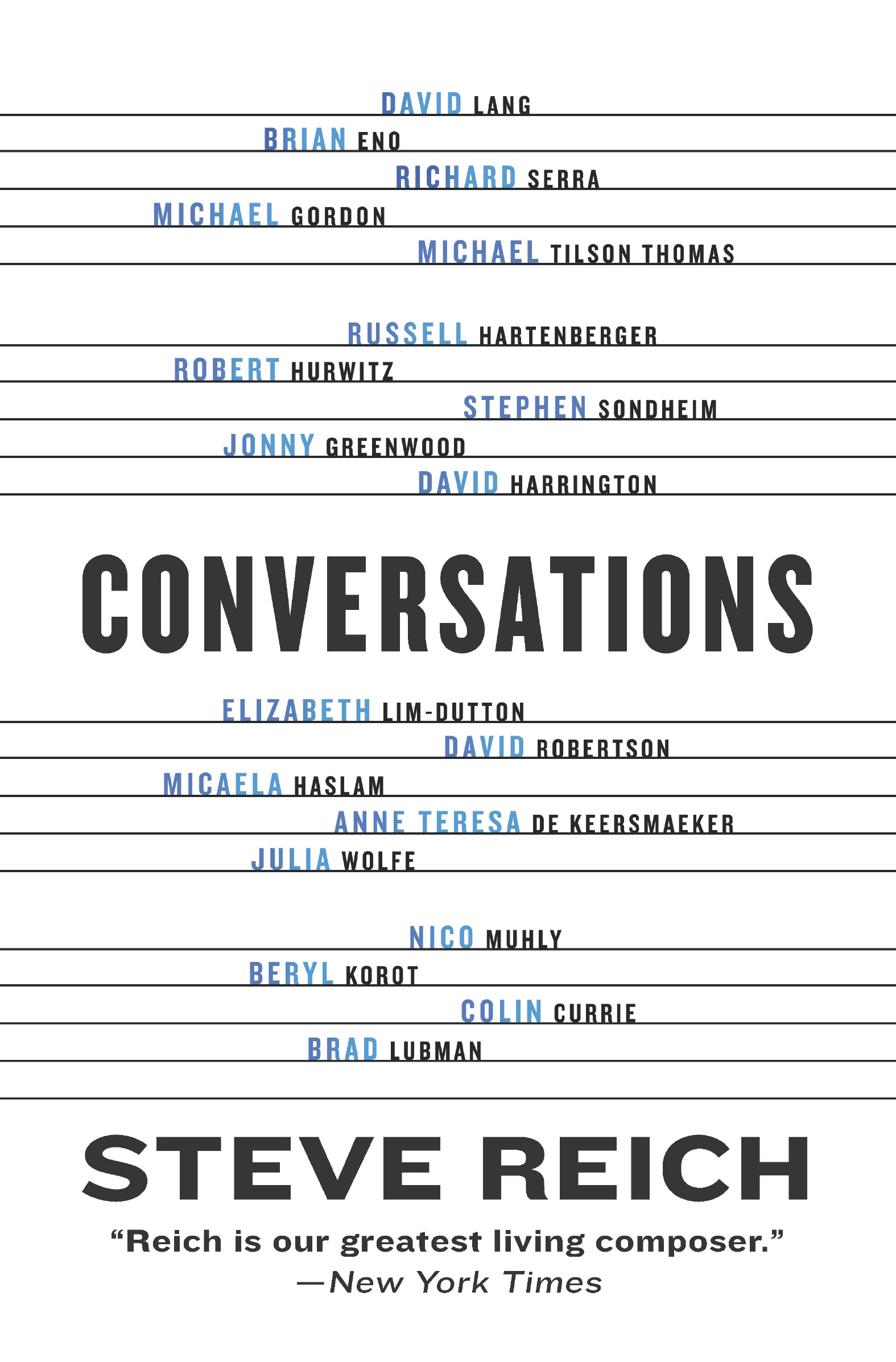

CONVERSATIONS

STEVE REICH

conversation

a talk between two or more people

- dialogue, discussion, observation, opinion, debate, give-and-take, small talk, reminiscence, exchange, questioning

...and man became a speaking spirit.

Genesis 2:7, translation by Onkelos

Contents

Preface

Whenever I thought about writing a book, one of my favorite music books always came to mind: Stravinsky in Conversation with Robert Craft. Stravinsky makes observations and recollections about his life and the great artists he was in touch with while Craft asks brief questions. While there was no one like Robert Craft in my life, that clearly opened up the inviting possibility of having many conversations. Composers, musicians, conductors, a sculptor, a choreographer, a video artist, and a record company president all came to mind, and it is my conversations with them that fill this book.

I spoke with David Lang, Brian Eno, Richard Serra, Michael Gordon, Michael Tilson Thomas, Russell Hartenberger, Robert Hurwitz, Stephen Sondheim, Jonny Greenwood, David Harrington, Elizabeth Lim-Dutton, David Robertson, Micaela Haslam, Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Julia Wolfe, Nico Muhly, Beryl Korot, Colin Currie, and Brad Lubman. I regret not being able to include conversations with artist Sol LeWitt, whose work and thinking somewhat paralleled my own, and impresario Harvey Lichtenstein, who presented so many of my works at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Both passed away before this book was begun. All these people helped create the unique musical/artistic environment in which I was fortunate to compose my works from the 1960s to the present.

Our conversations were almost all held via Zoom during the pandemic of 2020 and early 21. While we talked about my music in general, each conversation focused on one or more pieces that the other artist either performed or had a particular interest in. The order of the conversations is roughly chronological following the dates of the compositions discussed. Inevitably our discussions turned to the other persons work, as well, and given the variety of people involved, each with their own particular voice, every conversation inhabits a world of its own.

Steve Reich

May 2021

Chapter 1

DAVID LANG

David Lang: In the mid-1960s you began composing all these great, radical pieces, but before that, you were a student in a music school, being educated to be a normal, well-disciplined, European-oriented composer. I wonder if before we get into all the things youve done since then, it might be interesting to find out what your life as a student was like. You went to Juilliard?

Steve Reich: Yes, but best to go back before that, to when I was fourteen and discovered the music that really changed my life. I had piano lessons when I was younger, and I had heard Beethovens Fifth, Schuberts Unfinished, Wagners Overture to the Meistersinger, and lots of pop music, but at fourteen I heard a recording of The Rite of Spring, and it made an enormous impression. I had never heard anything like it. Then, a few weeks later, I heard a recording of the Fifth Brandenburg Concerto. Believe it or not, I had never heard any Bach before that. Finally, a bit later, a pianist friend played me records of Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, and Kenny Clarke, and we immediately said wed form a band. I said Id be the drummer and I began studying with Roland Kohloff, who later became the principal timpanist with the New York Philharmonic. All of those experiences starting when I was fourteen really laid the groundwork for the rest of my life. At sixteen I entered Cornell.

DL: You were young.

SR: I didnt know what I was going to major in. I was in a band playing drums on the weekends. I was listening to much more Stravinsky and Bach and discovering early music and Bartk, but I felt Bartk began at five and I was sixteen, so it was too late for me to become a composer. Fortunately, besides becoming very interested in philosophy and Wittgenstein in particular, I immediately took a history of Western music course with Professor William Austin, who was a musicologist, pianist, organist, and specialist in twentieth-century music. He taught the course as follows: first semester began with Gregorian Chant, went to the death of J. S. Bach in 1750, and then jumped directly to Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, and jazz. The second semester began with Haydn and ended with Wagner. Needless to say, I preferred the first semester, but more importantly, it clarified my instinctive attraction to Bach, Stravinsky, and jazz, showing how they all share a strong underlying rhythmic pulse and some form of tonal center. Nineteenth-century European Romantic music moves further and further away from both. Finally, the moment of truth came when I was a senior and had to make up my mind about where I was going. I applied to Harvard and was accepted as a graduate student.

DL: In the philosophy department?

SR: In the philosophy department. And I went to Austin and said, I cant do this. I want to study composition. He said, Why dont you study with Hall Overton, let me contact him. And he did, and I graduated from Cornell with honors in philosophy and went down to New York City to study composition with Hall Overton. You once mentioned you knew about him?

DL: Well, you know one of my hobbies, maybe my only hobby, is that Im a record collector. I collect LPs of musicians, American composers from the 50s and 60s. You run across his music in a lot of really interesting places. You find him in the symphonic world, and you find him as Thelonious Monks arranger.

Next page