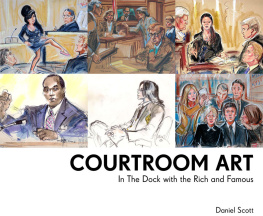

COURTROOM ART

COURTROOM ART

In the Dock with the Rich and Famous

Daniel Scott

CONTENTS

Introduction

I have never been inside a courtroom and I am keen to keep it that way. However, I am fascinated by much of what goes on within those walls. It is the place of ultimate judgement, where peoples lives are changed, sometimes forever. For those who like to control how they appear in public actors, politicians, pop stars, the super wealthy, indeed any celebrity the court is an unnerving place where they simply cant engineer the outcome nor rely on PR veneer.

Court cases play a major role in much of our news and celebrity media. We are all familiar with the comings and goings of those attending court: the tight-lipped, determined arrival with head held high, followed by the departure, showing relief and euphoria or bitterness and a feeling of injustice. However, it is what goes on between these two stages which intrigues me, especially as there are only a handful of people whose job it is to depict those unfortunate enough to find themselves in the dock. In the UK, while there is a small number of artists working on local cases, there are only three who work on the major trials. In the US, the already small number is dwindling as demand for courtroom art declines. The work of this select group of artists is seen by vast numbers of people on television and in newspapers.

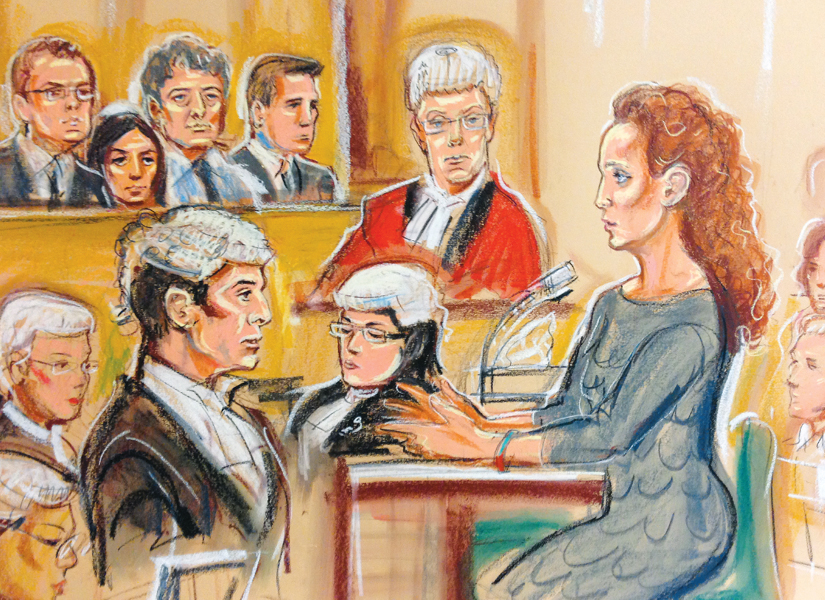

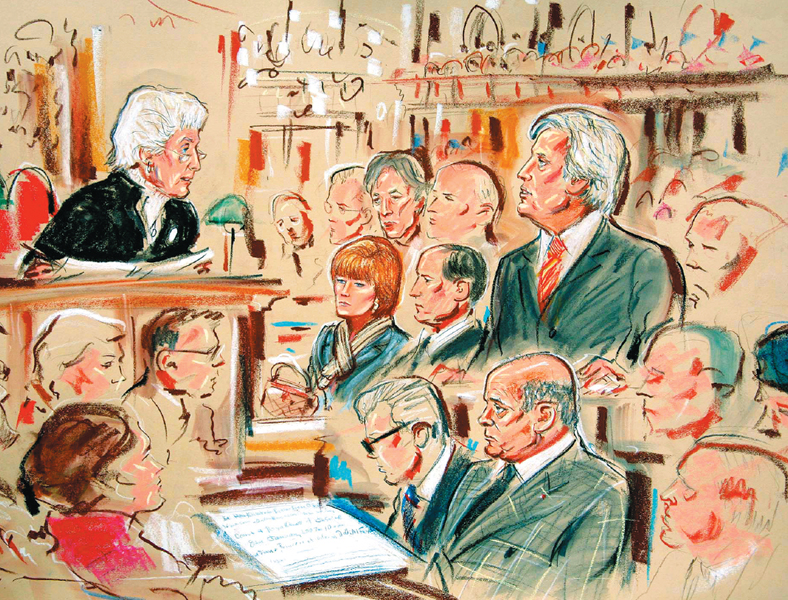

It remains illegal to film or to take photographs in court in many countries, so artists sketches remain the only visual record of these key events. Indeed, even in cases where photography is permitted, it isnt always the best medium. An artist can easily exclude those figures that cannot be identified in court, which is not always possible for a photographer. Courtroom artists can be barred from drawing alleged victims of sexual abuse, minors, jurors or some witnesses in high-profile trials.

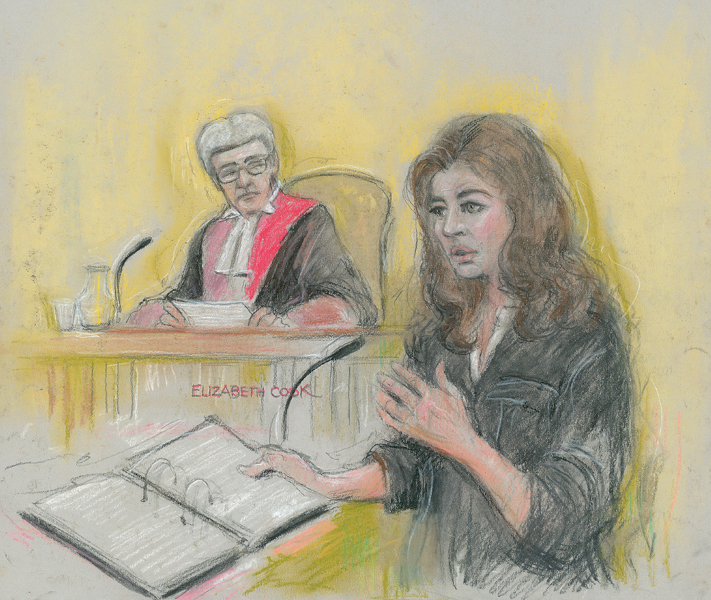

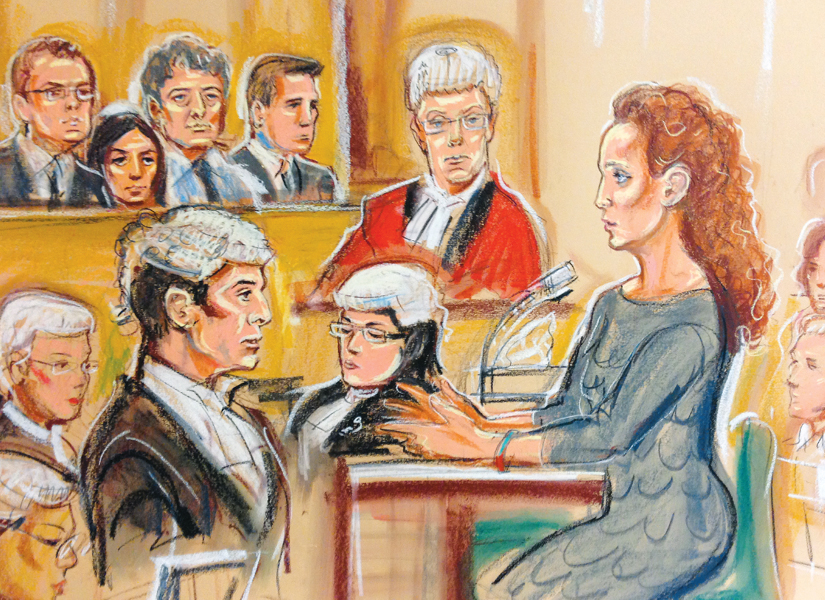

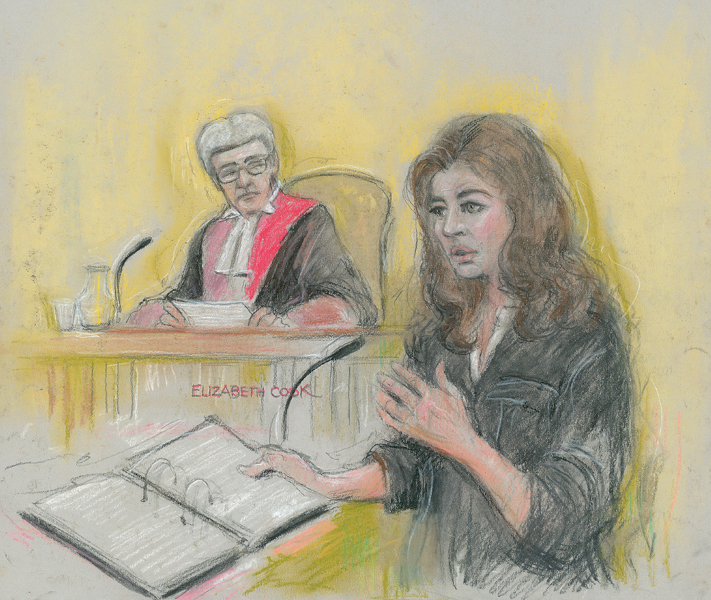

The sketches are commissioned by newspapers or television companies to accompany the news story. Curiously, in the UK, the drawings can only be made outside of court, so the artist must rely on a good visual memory; in the US, artists can work in court during the trial.

Courtroom art is not new, as we have always had a hunger to know the fate of others. In the US, there are illustrations of the Salem witch trials (16921693), albeit from some years after the event, and in 19th-century London, George Cruikshank depicted condemned men in Newgate Prison. It was the rise of celebrity culture, starting in the US, which marked the beginning of the modern trend in courtroom art. Television networks and newspapers began using sketches to illustrate events in court in the 1970s. As the media realised that court cases often brought out an intriguingly unvarnished side to a celebrity, the role of the artist became key to capturing this. Unlike a paparazzi photograph, with a courtroom drawing the artist can add nuances and shades which can often provide a fresh impression of a celebrity. Although the artworks like paparazzi shots are not consensual, they can often provide the defining image of a celebrity on trial.

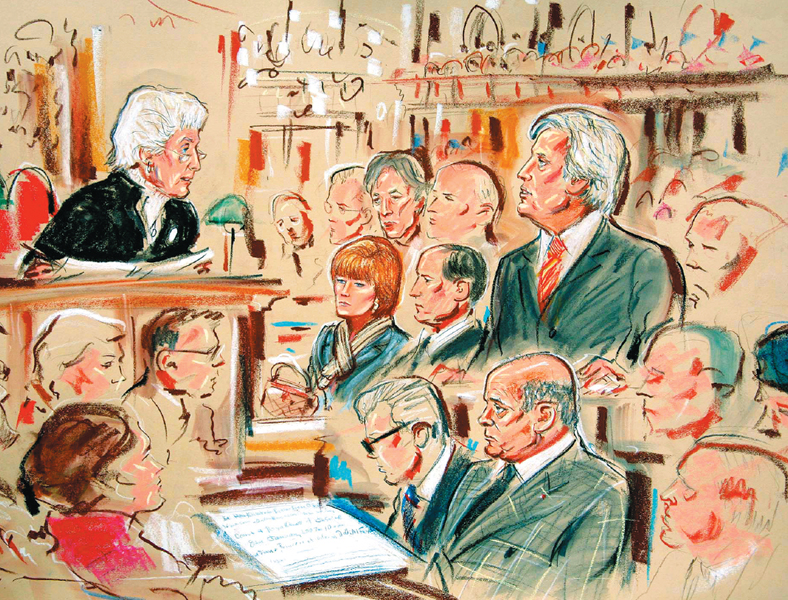

Having been commissioned to illustrate a trial, the artist will attend as a member of the public or as an accredited member of the media. In the UK, the artist can take notes to help create a framework from which they can work on the final sketches. The notes may be about distinctive features of the person or a fleeting expression that captures the persons mood. The drawings themselves will be produced outside the location in whichever venue is available, from the press room to, if necessary, the street. It is not unusual to see an artist at work outside the Royal Courts of Justice during a major trial. Each artist works in different ways, but, with the media having tight deadlines, the drawings need to be executed briskly anything from 10 minutes for a single figure to four hours for a more elaborate scene involving a large cast of characters. The sketches are then photographed a task made much easier with camera phones and sent to the media outlet with whom the artist is aligned. For major trials, there may well be more than one artist in court. In the US, the process is slightly different as the artist is permitted to sketch during the trial.

For major trials, with significant media interest Michael Jackson or the News International phone hacking case there might be a number of artists working in the same courtroom. Elizabeth Cook explained to me that they can work alongside the news journalists, who will prompt the artist to sketch a particular moment in a trial which they use to augment their words.

The appeal of the drawings extends beyond those watching or reading the news. The legal teams involved in the case or the celebrity in the dock will often acquire the artworks afterwards although, unsurprisingly, they tend to favour those cases that reflect best on them. In addition, institutional archives also procure artworks as a record of significant legal cases. Also, families of those in court sometimes acquire the works; for example Amy Winehouses mother bought Priscilla Colemans sketch of Amy, drawn during an assault trial where she was acquitted.

The artists have witnessed the full range of humanity in the courtroom, much of it grisly and unpleasant. The sketches I am most interested in are those of celebrities, both victorious and derided. The work of the artist can often be the key to how we end up seeing the celebrity after the trial.

In the following pages I have drawn on artworks from the US and UK, starting with Charles Manson in 1971. While Manson was not a widely known figure before his trial, the case was an early example of that heady brew of pop culture, celebrity and crime which has proved intoxicating ever since.

Interesting patterns emerge when looking at the range of celebrities and their court cases, with clear groups forming:

The Perennials Few would be in the least bit shocked to see Naomi Campbell, Courtney Love and Pete Doherty in court in the future.

The Predictables There are some people John Terry, Marilyn Manson and Snoop Dogg whose behaviour is so often chaotic that it is surprising that they had not been in court on occasions prior to when they actually did appear.

The Indignant Those defendants, including Paul Burrell and Jeffrey Archer, whose expressions in court imply that there has been some dreadful mistake and they should not actually be there.

The Reversal of Fortune In some trials, witnesses can enter court for one thing but find themselves under scrutiny for something completely different, as was the case with Nigella Lawson and Sienna Miller.

The Pivotal Cases There are some figures from the worlds of politics, media and celebrity who simply dont look the same at the conclusion of the trial as they had done at the beginning Tony Blair at the Hutton Enquiry, Rebekah Brooks at the phone hacking trail, and Max Clifford.

There is a view held that with the continued drive to use photography in trials, the role of the courtroom artist is under question and may die out in the near future. The artworks by the artists in this book highlight to me that, if this is the case, we would be missing out on a very distinctive and incisive gaze into celebrity culture at its moment of judgement.

Next page