The treasures of Rome and the Vatican, wonderful as they are, com prise only one small part of the riches of Italy. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that a visit to Venice and Florence is an essential experience for everyone hoping to experience Europes art.

With water everywhere, Venice offers a unique experience. Navigating canals to reach each church or gallery turns every visit into an adventure. Venice is also the one European city in which you can easily get lost without worry. No matter which tiny, unnamed passage way you follow, you will end up at a canal and find your way back to St. Marks Square.

Florence, Florence, you must visit Florence. It is a city of sculp ture Donatello, Michelangelo, Verrocchio, Ghiberti. It is a walking city, too touristy perhaps, but you must persevere. If you are careful to plan, and make reservations in advance, you will be able to avoid the horrendous lineups and spend your visit engrossed in your stunning surroundings.

57. Crucifixion

Tintoretto, Jacopo Robusti, 1565

Scuola Grande di S. Rocco, Venice

Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

Tintorettos Crucifixion in Venices Scuola Grande di S. Rocco is a circus of a painting with an evanescent Christ high up dominating workers, gawkers, potentates, hucksters, carpenters, crying women, and turbaned horsemen. Venetians in armour, Michelangeloesque workers are pulling, straining, and heaving, all in an eddy around Christ. Some viewers of wealth saddled on horses merely appraise, others gawk.

The Gospel of Matthew (27:3350) sets the scene:

And when they came to a place called Golgotha (which means place of a skull), they offered him wine to drink, mixed with gall; but when he tasted it, he would not drink it. And when they had crucified him, they divided his clothes among themselves by casting lots; then they sat down there and kept watch over him. Over his head they put the charge against him, which read, this is Jesus, the King of the Jews.

Then two bandits were crucified with him, one on his right and one on his left. Those who passed by derided him, shaking their heads and saying, If you are the son of God, come down from the cross. In the same way the chief priests also, along with the scribes and elders, were mocking him, saying, He saved others; he cannot save himself. He is the King of Israel; let him come down from the cross now, and we will believe in him.

From noon on, darkness came over the whole land until three in the afternoon. And about three oclock Jesus cried with a loud voice, Eli, Eli, lema sabach thani? that is, My God, my God, why have you for saken me? When some of the bystanders heard it, they said, This man is calling for Elijah. At once one of them ran and got a sponge, filled it with sour wine, put it on a stick, and gave it to him to drink. But the others said, Wait, let us see whether Elijah will come to save him. Then Jesus cried again with a loud voice and breathed his last.

The tumult of the crowd, the grief of the apostles, and the yearning of the penitent thief seem to come to a focus at Christs head. There is a sense of excitement. We see Roman soldiers, skittish horses, and workmen heaving the thieves up on either side. Christ appears high above the throng, lit before a darkening sky. It is all part of an inte grated scene a disciplined swirl of energy inhabits this very large canvas. There is tense anticipation, horses in a still quiver, all in separate flows of energy, yet joined by a grey lateral sky.

The underlying dark (the priming) dominates the picture, which looks as if the action was in the middle of a thunderstorm illuminated by sudden flashes of lightning, creating a rich darkness.

Ruskin accused Tintoretto of painting with a broom because of his brush strokes, known as prestezza, a series of rapid strokes that create an impression rather than detail. His contemporaries viewed this as deplorable hasty execution.

I suggest you take your binoculars and try to find the two men playing dice. Also find the ghostly silhouetted figures at the top right. See the anxious faces of the elderly in the left middle range. Who are the group in turbans on the left upper back? Note the workers, oblivious to all the opera about them, they are just concentrating on doing a heavy, sweaty job. The night, with its mixture of different groups, the sense of hustle, and the concentrated straining of the viewers make it a scene to remember.

By the fifteenth century it had become a convention to show the Virgin collapsed on the ground in a faint. The Council of Trent (154 5 63) issued a directive to artists that St. John (19:25) wrote, Near the cross stood his mother. Anyway, it suffered the fate of most civil servant directives it was ignored.

When I wrestled with this painting, I searched elsewhere in Venice for a better or easier Tintoretto crucifixion. There is one in the Church of San Cassiano. On the left wall of the choir is a composi tion of the crucifixion turned to the side so the congregation can see it. It haunts my mind, all grey clouds above crossed lances, the insignia of Christ being carried on the ladder above his head. Although surrounded by the other two and the insignia bearer, he is utterly alone. Perhaps it offers a more effective message.

58. The Baptism of Christ

Tintoretto, Jacopo Robusti, 157981

Scuola Grande di S. Rocco, Venice

Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

The Baptism of Christ in a translucent pool is framed by a lateral parade of distant observers all on a level a sort of chorus.

This work sends a shimmer of startling light piercing the crowds, rows of bending figures, ethereal compared to a muscular Christ bend ing under the water in the foreground. This special work mirrors a religious spirit.

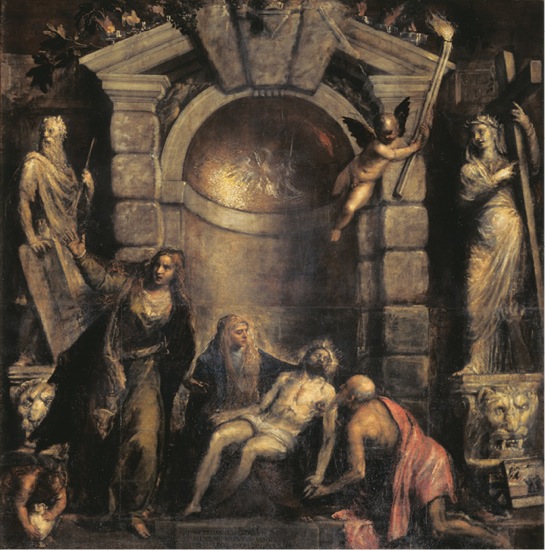

59. Piet

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), 1576

Accademia Art Gallery, Venice

Photo: Scala / Art Resource, New York

What strikes one immediately about this painting is its size. The paint ing is huge (353 x 348 centimetres). It is generally dark, making the strong red, blue, and green robes stand out. Titian is immersed in the painting, having used his fingers as well as the ends of paint brushes to apply paint, all to extraordinary effect. As a whole, the Piet is a viola chord of grief, pure, unadulterated, limitless grief.

Titian painted the Piet as the plague was gathering strength. Indeed, he himself was a victim of the plague and died before he was able to finish the work; the final touches were completed by Jacopo Palma.

In the painting, Christs chest is rent. One can see how Titians fingers kneaded the grey-white paint. Exhaustion and illness are rep resented, the moment of transition suggested. One can detect a hint of resurrection, dead yet not dead.

And Mary Magdalene so angry! Hers is the haunting power, the resonating figure that lingers in ones memory. Maybe Mary Magdalen e, with Moses and the Sibyl woman, holder of the cross, are all looking towards resurrection as predicted.

The square blocks made of hewn heavy stone that make up the huge nich e where this drama unfolds give it a blunt gravitas, evoking permanence.

In the painting, the half-naked old man called variously Nicodemus, Joseph of Arimathea, St. Jerome, or even Job, lies prostrate asking for intercession by God for the next life. Nicodemeus approaching the Piet is a self-portrait of Titian.