ALSO BY NICK M C DONELL

The Civilization of Perpetual Movement: Nomadism in the Modern World

Green on Blue

The End of Major Combat Operations

An Expensive Education

The Third Brother

Twelve

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Nick McDonell

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Portions of chapter 15, Record Keeping in the Emergency Room of the Baghdad Teaching Hospital, previously appeared in the London Review of Books 38, no. 9 (May 5, 2016).

All photographs are by the author unless noted otherwise. : Photographer unknown; photograph provided by Zabiullah Zarifi.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

Ebook ISBN 9780735211582

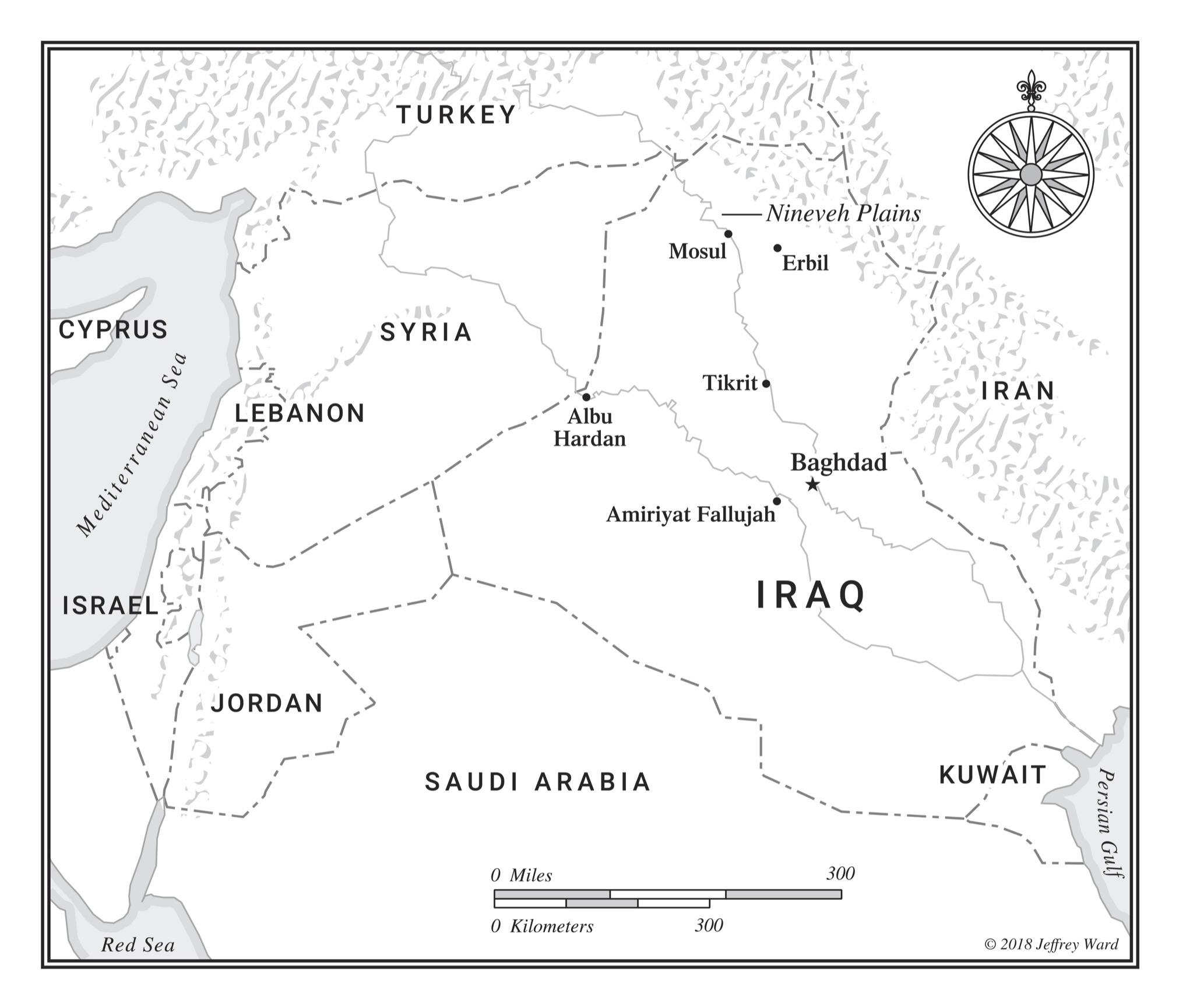

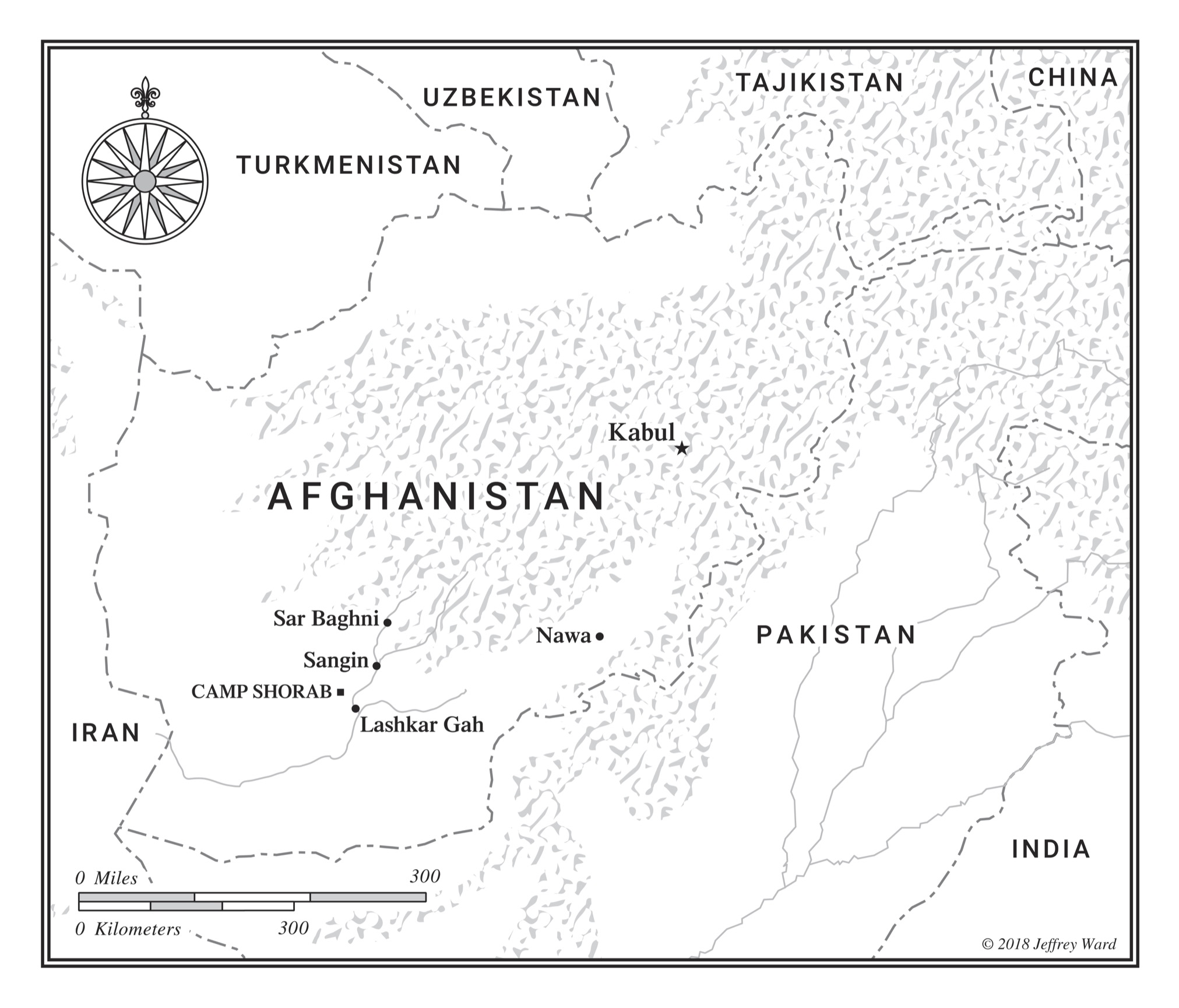

Maps by Jeffrey Ward

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity.

In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers;

however, the story, the experiences, and the words

are the authors alone.

Version_1

Contents

I didnt always think this way. Im an American born in 1984, and halfway through my life my country went to war abroad. For a combination of reasons not unusual among young men, I went too. After the initial bloom of romance around working in places where America was at war, hoping to get shot at without getting shot, I believed the best path was to channel local populations in writing and scrub my voice as much as possible from the pages. Ive attempted that a few times, tried also to launch projects that move resources faster than words on a screen. But life splinters plans, and ten years into visiting these places and thinking about my own country its clear to me that some other kind of reckoning is due.

Since autumn of 2001, after nineteen men hijacked and crashed passenger jets into skyscrapers in New York, a military headquarters in Washington, D.C., and an open field bordered by conifers in Pennsylvania, America has been killing civilians in Afghanistan. For nearly as long, and in earlier wars, it has been killing them in Iraq. No one disputes this. The dispute is only over how many, why, and whether the why justifies the killing. Some say America is benevolent, a force for good. Others say its a brutal empire. Many observe complexity, and many more are not interested in thinking about these questions at all.

Like prayer, Ill state here at the beginning that America, Iraq, Afghanistan, and all the others represent incomprehensible multitudes,

I began several trips like that in the tidy city of Erbil, Kurdistan, northern Iraq. Erbils not at all like the frantic Hollywood movies about the Middle East. The airport is better than John F. Kennedy International, New Yorks main airport. The streets are dusty but otherwise clean, people hang out in malls. For a while, most foreign reporters covering the war in Iraq were based in Erbil.

I stayed in the Classy Hotel. The name was funny in a way you never had to explain. There was a short pool in the basement in which I swam laps while a vastly obese Iraqi gentleman watched his son bob on inflatable water wings. The lobby was a popular meeting place for contractors, aid workers, and war profiteers, only a few hours drive from the fighting by a good road across the Nineveh Plains. The best-known American newspapers kept correspondents in residence. I stayed on a discount rate, courtesy of a friend, a bureau chief at the time.

I was grateful for the discount. Reporting was expensive and the economics of media were, and remain, uncertain. In fact, as I have been writing this book, the company that paid for itPenguin Random House, majority-owned by the multinational Bertelsmannhas closed down the imprint under whose aegis it was purchased. A lot of people at the Classy were likewise negotiating unstable industrieslooking for jobs, doing good work with barely a boss to pitch. A photographer whose business card read human; an ex-soldier trying to break into Hollywood; a graduate student trying to break into tenure. You would see them at breakfast, faces to their phones, perhaps a table over from the tattooed mercenaries pouring miniature bottles of whiskey into the mornings coffee. I had a lot of conversations with all of them. Mostly variations on the same conversation, revolving around a handful of questions.

What do you do?Who do you work for?

In my case, according to market research: 60 percent of American book buyers are women, 61 percent are college educated, and 63 percent earn an annual income of $50,000 or more. You could usefully pick a wider variety of numbers to address in this context, but the point, in the conversations, was that any reflection on audience, whatever the job, led to the question of intent, and in turn, resource allocation.

Why are you doing it?Is it effective?

At the time, at the Classy, I hadnt yet come to many conclusions. In anglophone war histories, memoirs, and close anthropologies, such questions are often left up to the reader, you, to decipherthough some clear answers have been articulated. In his famous essay Why I Write, George Orwell provides four: sheer egoism; aesthetic enthusiasm; historical impulse; political purpose. It can be seen, observes Orwell, how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. Orwell explicitly puts aside the question of income:

How do you pay for it?

The answer: one way or another, like everything else. When I signed the contract for this book I was paid $85,000; Im owed an additional $140,000, to be paid in pieceson delivery of the manuscript, on publication, and then on its first anniversary. I began the work in August 2015; publication is planned for September 2018. This divides out to $75,000 per year with which to live and cover expenses. Im fortunate to have this deal, and to have had money saved that I could spend along the way. Without the savings, the reporting would have been more time-consuming, less safe, perhaps impossible. This is part of why a disproportionate number of human rights and conflict researchers come from the middle classes and above. The implications are many. One is that information about innocent death in foreign wars is most accessible to Americas cosmopolitan wealthy, even though its mostly the working classes, domestically and abroad, who become casualties.