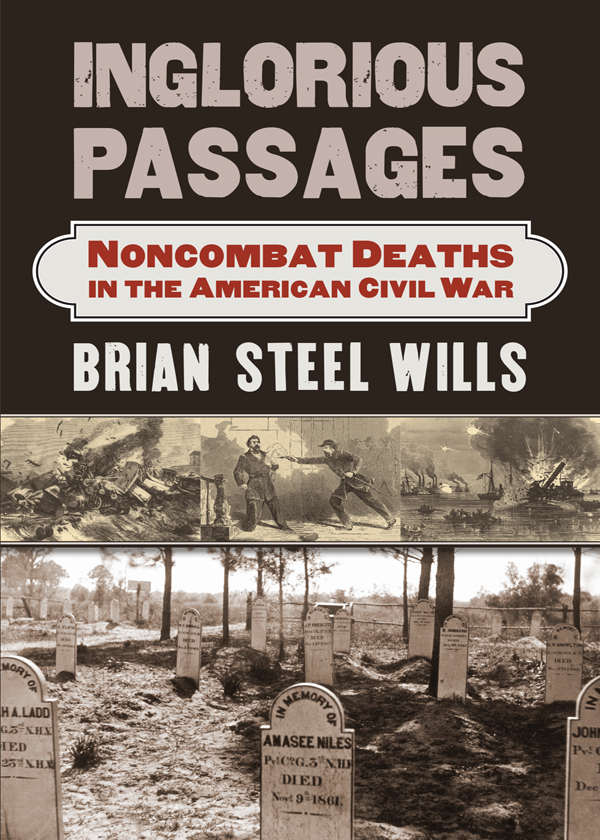

2017 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wills, Brian Steel, 1959 author.

Title: Inglorious passages : noncombat deaths in the American Civil War / Brian Steel Wills.

Description: Lawrence, Kansas : University Press of Kansas, 2017. | Series: Modern war studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017038280 | ISBN 9780700625086 (cloth: alk. paper) | ISBN 9780700625093 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: United States1History1Civil War, 1861118651Casualties. |United States1History1Civil War, 1861118651Social aspects. |Soldiers1United States1Death1History119th century. | War casualties1United States1History119th century.

Classification: LCC E468.9 .W58 2017 | DDC 973.7/1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017038280.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is recycled and contains 30 percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1992.

To all who served and sacrificed their last full measure,

And in memory of friends and historians

Wiley Sword, Mike Ballard, and Martin Ryle.

Leading military historian John Keegan examined the face of battle by focusing on the iconic European engagements of Agincourt (1415), Waterloo (1815), and the Somme (1916). He opened his study with an admission that although he had read and studied about the battlefield extensively, I have never been in a battle. And I grow increasingly convinced that I have very little idea of what a battle can be like.

That scholar and I share that history. Yet, clearly, Keegan wanted to come to understand better the experience of the battlefield and the degree to which that ordeal evolved over time. He also recognized that even in combat, death came from sources other than enemy weapons. Accident has always caused a portion of battles deaths and wounds, he observed. Whether the suffocation of soldiers beneath the press of bodies at Agincourt or the accidental discharge of weapons at Waterloo and the Somme, men died who might not otherwise have done so. He offered no statistic as foundation for the assertion, but his point remained clear. Men have perished in wartime outside of the context of hostile fire on the battlefield or under unexpected circumstances on it.

However, the British historians argument was not the reason I undertook this study. In The War Hits Home, published in 2001, I attempted to examine and assess the experience of warfare from 1861 to 1865 in the community in which I was reared: Suffolk, Virginia, in what was then Nansemond County, and the surrounding area. I found that there were powerful and often poignant stories of fatal accidents and encounters and collateral civilian deaths that occurred in that region during the Civil War. I wanted to allow such stories as those to be told and known, apart from the cold calculations of statistics, even when the causes of those ends reflected no sense of the sacrifices that could be expected from combat. In each case, they represented the harsh realities that the loved ones who had gone off to war were not going to be returning home to renew their lives and rejoin their families once the formal hostilities were ended.

Part of the motivation for this work also came from popular culture. As a young person, one of my most enduring family experiences was watching the motion picture Shenandoah, in which Jimmy Stewarts Charlie Anderson attempted desperately and ultimately unsuccessfully to avoid the war raging around him and prevent it from affecting adversely his tight-knit clan in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Although Anderson and his sons never enlisted for armed service, the conflict nevertheless impacted the family when circumstances led to the deaths of several of its memberstwo killed by roving soldier deserters and another by a startled youthful Confederate picket. After Anderson and his entourage of family members returned from an unsuccessful search for the missing youngest childthe Boythe empty chairs around the table in the Anderson household reflected these unintended and inglorious passages as the remaining members of the clan gathered for their meals.

The Charles Humphreys story that leads this work came later, but it seemed perfectly suited to putting into contemporary words what I wanted to say. The same sentiment was true for civilian victims of the conflict. Some of these individuals perished while caught up in battles that reached their homes or communities or in factories and under other circumstances associated with wartime production and supply. These final encounters happened for each of these people, often in situations they could not have imagined and with a cost that their loved ones were required to endure.

Many individuals and institutions have assisted with the research for this work. The efforts of many colleagues in the profession to edit and produce letters, diaries, and other memoirs have been essential to this project. Likewise, the Library of Congresss excellent website Chronicling America has proved indispensable for reaching newspaper sources. Individually, many people have offered assistance in various ways. Wayne Willingham graciously provided examples for use in the volume. Nick Picerno sent a volume of letters and several references for inclusion pertaining to Maine soldiers. Jim Ogden offered numerous examples. Ann Gunnin shared her volume, Letters to Virtue, on her kinsman Charles W. Sherman after a talk I presented at a meeting of the Clara Barton Tent in Georgia.

During my semester as Lewis P. Jones Professor of History at Wofford College in Spartanburg, South Carolina, my colleagues were not only extraordinarily gracious but also helpful in allowing me to make my public presentation on this topic and use the materials in the library and archives for research. Thanks especially to colleague and friend Tracy Revels and to Phil Stone in the library for their support.

My own Department of History and Philosophy and the Deans Office in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Kennesaw State University have been likewise supportive. As always, Randy Patton, my colleague, friend, and former officemate from graduate school at the University of Georgia, has been a bulwark. The Center for the Study of the Civil War Era, of which I have had the privilege of serving as director since 2010, has allowed me the freedom to engage in research and writing when I am not undertaking other activities to support the centers programming and operations.

University Press of Kansas

University Press of Kansas