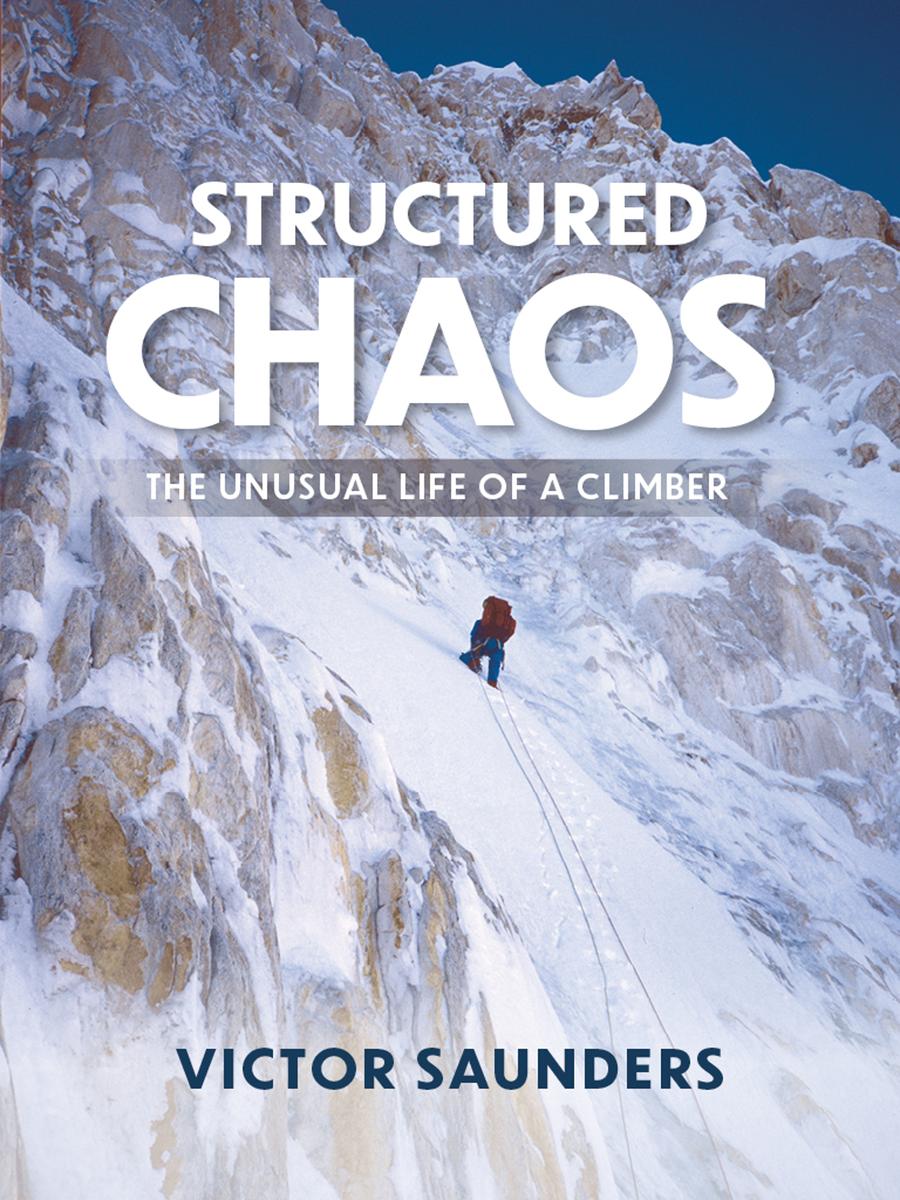

Victor Saunders is a remarkable man. Over his seventy years he must have accumulated the potential for a near-unlimited number of riveting real-life short stories. Structured chaos is the way he describes his life so far but it has been a wonderfully productive kind of chaos. Whether it be on extreme mountain adventures or in social situations, Victors writing brings out that he invariably leaves a deep impression on those that meet him. After our first meeting, in Chamonix high street, I was so bowled over by his irrepressible questioning about a route I had just climbed that I cheekily wrote that I found him an irritating little squirt. He responded by writing that he found me insufferably arrogant. And so started a deep friendship that has endured for over forty years. That ever-questioning side of his personality is still there, of course and it resonates strongly throughout this book. He moves in an ever-inquisitive manner from one adventure to the next; the reader will soon appreciate that he is a man of many talents and a master at self-deprecation. That chaos he refers to should not mask the intelligence and focus that has led to award-winning books, six ascents of Everest, the longest sea-cliff traverse in Britain, and a host of adventurous first ascents on rock, on ice and in the Himalaya.

But this book is not so much about achievements. It is about friendships, personalities, experiences and a journey through life. Whether viii it be harsh bullying at school, sweatshop labour in ships, saving lives, traversing mud cliffs or pushing boundaries in the Himalaya, his sharp prose weaves the different facets of his varied life into a vivid and immensely enjoyable read. Read on and be prepared to be left reeling at the breadth and number of intense experiences that he has squeezed in so far. And he is still going strong.

Mountains have given structure to my adult life. I suppose they have also given me purpose, though I still cant guess what that purpose might be. And although I have glimpsed the view from the mountaintop and I still have some memory of what direction life is meant to be going in, I usually lose sight of the wood for the trees. In other words, I, like most of us, have lived a life of structured chaos.

A mountaineers life is not without risk. Although thats rather obvious, isnt it? And anyway, all lives contain risk. As for managing those risks, we like to think thats all about making good decisions, in day-to-day life as well as in the mountains. Even though good decisions are based on experience, which in turn is gathered from the consequences of bad ones. Well, perhaps. We tell ourselves, this way lies truth and that way lies well, just that: lies. We try to look ahead, to envision the destination, as we stagger, sometimes knowingly, more often blindly, through the dark forest of decision trees that make up our existence.

On this confusing journey, this wandering through the woods, my best guides have been my unspeakable friends with their incomprehensible ideas and impossible beliefs. Decisions are made difficult because I believe, like most of my friends, in many contradictory things. x Heres an example: the Sybarites Creed and the Climbers Creed.

Sybarites Creed: Never bivouac if you can camp. Never camp if there is a hut. Never sleep in a hut if you can book a hotel.

Climbers Creed: If you were not cold, you had too many clothes. If you were not hungry, you carried too much food. If you were not frightened, you had too much equipment. If you got up the climb, well, it was too easy.

I believe in both creeds, wholeheartedly and without reservation.

I got to be this way not through design or planning, but through Brownian motion, following an erratic path, knocked this way and that by people, mostly those self-same unspeakable friends.

It has taken me a lifetime to realise that, all the while, it was people and not places I valued most. I have now been on more than ninety expeditions, accumulating seven years under canvas. I have climbed on all continents, many of the trips involving big adventures and occasional first ascents. And yet it is not the mountains that remain with me but the friendships. In 1940 Colin Kirkus said: going to the right place, at the right time, with the right people is all that really matters. What one does is purely incidental.

This book is about what really matters.

(19541961)

Each time Id woken during the journey, as the night bus from Singapore lurched from one pothole to the next, Id seen a strange, obsessed look on the drivers face. Sometimes he would gun the engine until the bus was taking corners on two wheels. I managed several times to get back to sleep, but dreamt only of news headlines:

BUS PLUNGE IN PAHANG!

Sixteen killed, including lone foreigner! The Kuantan News Agency reports that bodies were difficult to identify after the high-speed crash, probably the result of driver error. The Kuantan News Agency

Kuantan! Wake UP! This Kuantan. KUANTAN!

I rubbed my eyes and staggered off the bus. The driver really had been in a hurry; it was 4.30 a.m. and we werent due in for another two hours. Yet here we were: safe, alive and early in Kuantan, the main city on the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia. My next bus, to the small town of Pekan, left in an hour. At the station cafe, a group of road people, Malaysians and Thais and Cambodians, were having an early morning breakfast. I joined them. Roti chenai and tea made with condensed milk. The roti was a particularly skilful effort, the cook spinning out the dough into crpe-thin pancakes before folding them over into small buns, and serving them with coconut curry sauce. But I was still half asleep when the local bus arrived, the slow coach to Pekan, slow because it stopped every few minutes for schoolchildren and agricultural workers along the way. I began to think that reaching Pekan was analogous to a mountain climb, not least for the persistence in goal-seeking.

I had come here in the year 2000 looking for a connection with my childhood. Pekan is where I spent the first decade of my life, running around half naked in the tropical rain and sun with my younger brother, Christopher. We did not know it then, but in hindsight it was paradise. After growing up in the Elysian jungles of Malaysia, we returned to the British Isles, where Christopher and I were incarcerated in a miserable Scottish boarding school.

By then our parents had separated completely. Our father, George, ran a small import business in Gloucester. Our mother, Raiza, scraped together a paupers living in London. I remember how she had once visited us at school, taking the train to Aberdeen, missing the connection and, in order not to give up spending a few hours with us, taking a taxi to the school. This was in 1963, when a cab ride of that length was more than a weeks wages for most people; it must have taken my mother months to save for the journey. But her visit was the best gift of my childhood. This obsession with seeing journeys through, I inherited from her.

I had arrived in Singapore fresh from the Himalaya, although fresh isnt perhaps the right word. You dont arrive anywhere fresh from a Himalayan climb. I had arrived worn out from a spell of exploration and the first ascent of Khoz Sar, a 6,000-metre mountain near the PakistanChina border, climbing with Phil Bowker, a software engineer from Belfast. In Singapore, I had been the guest of the Singapore Mountaineering Association, which like its hometown was in the ascendance. In the 1990s its members had organised a series of bold expeditions with near-Teutonic planning, culminating in an ascent of Everest. My lecture was done, and now I had three days spare. Three days in which to rediscover my childhood home on the edge of the Malayan jungle. After that I would go home.