Table of Contents

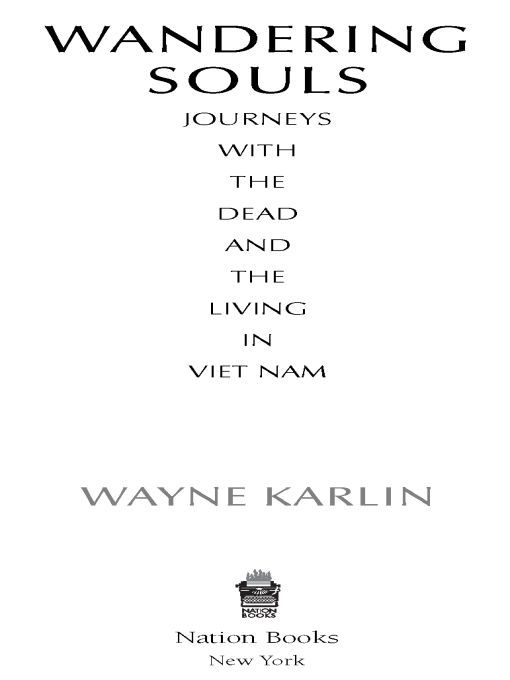

ALSO BY WAYNE KARLIN

NOVELS:

Crossover

Lost Armies

The Extras

Us

Prisoners

The Wished-For Country

Marble Mountain

NONFICTION:

Rumors and Stones: A Journey

War Movies: Scenes and Out-takes

AS COEDITOR/CONTRIBUTOR:

Free Fire Zone: Short Fiction by Vietnam Veterans,

with Basil T. Paquet and Larry Rottmann

The Other Side of Heaven: Postwar Fiction by Vietnamese and American Writers, with Le Minh Khue and Truong Vu

Truyen Ngan My Duong Dai (Contemporary American Short Stories), with Ho Anh Thai

Love After War: Contemporary Fiction from Vietnam, with Ho Anh Thai

To all the wandering souls, dead and living, from the Viet Nam War.

CHAPTER ONE

An Encounter in Pleiku

On March 19, 1969, First Lieutenant Homer Steedly Jr. turned a bend in a trail in Pleiku Province and came face-to-face with a North Vietnamese soldier, his weapon slung over his shoulder.

Homer stared in astonishment. At first it was almost surreal. I mean, were all in green fatigues, muddy and sweaty, and really looking like guys in the field. Here this guy comes around the corner, and hes got on a light khaki uniform, a clean light khaki pith helmet. Youve seen the red Pleiku mud. You cant stay clean up there. Youre tinted red. Your uniforms are red, your fingers are red, its justit gets everywhere. And heres this guy thats walking down the trail perfectly clean. Perfectlynot a wrinkle anywhere. I mean, not a hair out of place. I must be hallucinating, the heats gotten to me.

The soldier he was confronting was a twenty-five-year-old medic named Hoang Ngoc Dam, from the village of Thai Giang in Thai Binh Provincea fact the lieutenant would not discover for over three decades. There was no time then for more than a quick glimpse of each other. As soon as Dam saw Homer, he snatched his weapon off his shoulder and began to bring it around. Later, Homer would recall how he shouted, Chieu Hoi, the phrase he thought meant surrender.

For a time he stared at the body, dazed. He noticed more details. Not only was the young mans uniform starched, but the SKS rifle clutched in his hands still had the greasy cosmoline used as an antirust agent congealing on its bayonet hinge. Someone new to the war, Homer concluded, probably an officer; in his description of the incident in a letter home, he called the dead man a major. He was wrong on both counts. Dam, whose rank was sergeant, had already been in the war for over five years by that time; he had survived the Tet Offensive and many other major battles.

Homer bent down and went through the dead mans pockets, drawing out a notebook with a colorful picture on the front cover of a man and woman in what he took to be traditional or ancient Vietnamese dress, and on the back cover, a daily and monthly calendar grid, labeled with the English word schedule; a smaller black notebook; and a number of loose papersletters, ID cards, and some sort of certificates. The spine and corners of the first notebook had been neatly reinforced with black tape.

Thirty-six years later, when I first touched that notebook, I was struck by the care Dam had taken in binding it up. He was a soldier in an army where nothing could be thrown away, nothing wasted. I thought of what the appearance of that book must have meant to Homer as he looked through it on that dark trail. Raised on small, hardscrabble farms, Homer knew the precious-ness of things that could not be replaced. The way he had shot Dam was unusual: a gunfighter duel in a war in which more often than not the enemy remained faceless to the Americans, only sudden flashes of fire from the jungle, targets to be annihilated. That invisibility was frustrating to the GIs, but at least it allowed them the comfort of dehumanizing the enemy, making him into ghost, demon, target. Now to see not only the face of the man hed killed, but also the carefully re-bound covers, the force of will that the meticulous writing and drawings inside the book revealed, confronted Homer with a mirrored and valuable humanity. He tried not to think about it. There had been no time to think, anyway. His enemy had been armed and ready to shoot him. Homer had simply been quicker. It was what could be, and was, called a good kill.

Homer sent the documents to the rear area, where he knew theyd be assessed and then burned. But later that evening he changed his mind. He contacted a friend in S-2, intelligence, and asked him to bring everything back. Homer couldnt bear to have the documents, the last evidence of the life he had taken, be destroyed.

CHAPTER TWO

Eyes Like a Mean Animals

Had he and I but met

by some old ancient inn,

We should have sat us down to wet

Right many a nipperkin

But ranged as infantry,

And staring face to face,

I shot at him as he at me,

And killed him in his place.

I shot him dead because

Because he was my foe,

Just so: my foe of course he was;

Thats clear enough; although

He thought hed list, perhaps,

Off-hand-likejust as I

Was out of workhad sold his traps

No other reason why.Yes; quaint and curious war is!

You shoot a fellow down

Youd treat, if met where any bar is,

Or help to half-a-crown.

THE MAN HE KILLED by Thomas Hardy

Icant think of Homer and Dams fatal meeting without being reminded of that Thomas Hardy poemand of Tim OBriens update and personalization of it in The Man I Killed, a story chapter in The Things They Carried. Homers need to clutch some grief to himself by hanging onto Hoang Ngoc Dams documents can be seen in the thoughts and actions of Tima character subversively created and named after himself by OBrienwho has, like Homer and the persona in Hardys poem, just killed an enemy soldier and cannot stop staring at the body. The description of the dead mans face is repeated, over and over, so that we understand Tims inability to tear his eyes away, his shock and horror at what hes done. As he stares at the corpse, he creates a life story for the dead Viet Cong soldier spun from the mans frail, unsoldierly physique and the objects pulled from his body, including a photo of a young woman next to a motorcycle. He imagines the young Vietnamese as someone who loved mathematics, had gone to the university in Saigon, had fallen in love and married, had been reluctant to go to the war, but finally hadmainly because he feared disgracing his family and his village. Like Homer, who at first imagined Dam as a young officer like himself, Tima former university student whod been reluctant to be drafted and had only gone to war because he feared being ostracized by his family and communityhas projected his own life onto the life of the man he has killed. He has killed himself, and he refuses to stop staring at the mirror of his own corpse, to stop grieving for the loss of his own common humanity.