In memory of Kit

Virginia

In memory of Boyd

Janice

In 1998, Virginia Pawsey (ne Sinclair) organized a reunion of our small class of Seventh Formers from Gisborne Girls High School. We spent Waitangi Weekend in Gisborne reacquainting ourselves with classmates we hadnt seen since our last school assembly.

Gillian organized a picnic for us in Eastwoodhills Arboretum. It was hot. We sat around a picnic table and, while the almost-forgotten power of the Gizzy sun beat down, each of us told our life story. Virginia and I had led totally different lives. However, we had also both suffered tragic bereavements. And we both loved our gardens.

Before the weekend was over, we all did what Gisborne girls always did then and still do todaywe all went to the beach and threw ourselves in the surf. Then everyone scattered, back to their own worlds. The Wainui tide swirled in and pulled back out, and the sand was wiped clean.

Virginia and I started emailing each other. Weve never stopped emailing since. Common Ground is a selection of those emails.

Bunsen the dog, often referred to in the emails, died of old age before this book went to print.

He had spent a happy life in the garden, relishing its convenience the way we humans would a large top-opening freezer. He only had to dig down a bit to find stored food. I am still pulling those cannon bones out of the soil today. I put them under the compost bins. It helps with air flow. We try to ignore the fact the bins are getting taller and taller and looking more and more like Baba Yagas hut.

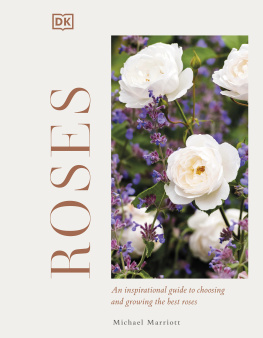

Bunsen is buried in his own special part of the garden. Six Hills Giant catmint flourishes above him. It might be inappropriate, but it looks beautiful.

Janice

Thanks, from both of us, for the terrifying tutelage of Miss Duff and Miss Bullen, Principal and Second in Command at Gisborne Girls High School, and to Miss Bagley, Miss Knaggs, Mr Simpson and Mr Cruttenden, who taught us not only that girls must wear their hats at all times and never ever face outwards from the hockey field to watch Gisborne Boys High boys biking past, but alsohow to write.

An acknowledgment is also due, painful as the recollection is, to The ABC of English Usage, a book we had to learn by heart.

My garden lies between Tinakori Hill and the Wellington motorway in an area of tiny lanes and old cottages. The house sits in the middle of the section. In front of the house is a parking area, and a carport which is almost completely covered by an Albany grapevine. The verandah has roses and wisteria hanging from the eaves, and bog sage, sweet peas and annuals in the beds in front of it.

My letters to you will be about the back garden, a hortus conclusus hiding behind a trellis gate that is itself hiding under a rhodo and a fuchsia. When you open the gate, theres a densely cultivated garth of vegetables, fruit trees, roses and flowers. Theres also a deck, and a black plastic paddling pool for the exclusive use of the houses large Labrador, Bunsen.

The garden square is 13 metres long and 8 metres wide. Two diagonal concrete paths divide the square into four triangle beds. On the deck are a table and chairs, pot plants, and a pile of bones. To the side of this rectangle, there used to be a small lawn, lovingly laid out by the son of the house. It was to be the deck chair area, a place from which to survey the garden through the gap in the feijoa hedge. As soon as the sprinkler was turned off and the grass established, however, this little lawn was claimed by Bunsen as his en suite.

We are sheltered. The garden is surrounded by corrugated-iron fences, and by the iron roofs of the neighbouring cottages. There are townhouses to the south, a neighbours tall trees to the north.

Dwarfing all this hangs the long green curtain that is Tinakori Hill to the west. When Parliament is welcoming overseas potentates with blasts on military trumpets, or when Wellington Cathedrals bells peal on Sunday mornings, the sounds reverberate from the hill all around the garden, reminding me of other peoples ideas of power and glory. I just go on digging.

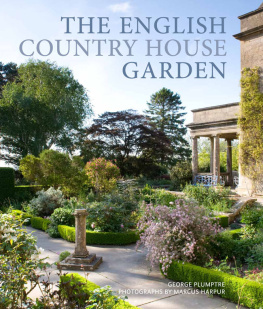

I feel at a tremendous advantage in this exchange for I have stood in your garden on a balmy summers morning in February, whereas you have not set foot in mine. Your garden, in my mind, will be forever a summer garden, festooned with rampant growth and vibrating with the chorus of the cicadas. You dared hiss at them to shut up.

There are no cicadas in my garden, a farm garden at Double Tops in the hills back of Hawarden in North Canterbury, elevation 500 metres. The summers are fickle, stalked by rogue frosts and harsh winds. Trees guard the garden from the worst ravages of the prevailing norwest wind: to the west, old man pine trees and Lombardy poplars; to the east, more poplars; and to the south, tall eucalyptus trees; only the north border is open, to admit the sun. We live inside the barricades in a white weatherboard farm house. The garden is a haphazard mix of shrubs, roses, perennial borders, flaxes, lawns and trees. My favourite, most loved, and most cared-for part of the garden is the vegetable garden where I grow all the vegetables we can eat. To the east of the vegetable garden, a sheltered paddock guards a raspberry frame and a hen house.

Beyond the sheltered paddock and through a little wooden gate, there is a pondKits pond. The pond is shadowed by flax, cabbage trees, ribbonwoods, lacebarks and kowhais. Mallard ducks and a pair of pukekos loiter at the waters edge. A large rock which we carried in from the hills sits amongst the flax and tussocks. A bronze plaque on the rock faces the sun; it commemorates the life of Kit and the thirteen who died with him at Cave Creek. I can look out my kitchen window, across a tangled bed of shasta daisies, fallen delphiniums and roses, to the rock and the brass plaque. The plaque reflects the light of the sun in the early morning and the pale glow of a full moon at night; I remember Kit as a small boy playing in the duck pond, looking for tadpoles with his dachshund Fritz.

My garden does not stop at the fences and gates that keep the cows and the sheep and the horses from the door; it reaches out to include the whole of Double Tops. I like to think the farm is a large and unruly extension of my garden. The rolling paddocks, the tussock hills and the rocky outcrops, the swampy gullies and the slow-flowing creeks, the remnants of sooty beech forest and the thorny matagouri, I know them and love them as I know and love the managed garden. But, and this is a deep secret, sometimes, when the wind is screaming and trying to suck the hair from my head and Im spattered with mud, when the cold is freezing my eyeballs and paralysing my hands I wish I lived in the city and drank lattes at brunch.

P.S. We have a house dog as well as our eleven working dogs. His name is Henry, a miniature dachshund. He sends kind regards to Bunsen and has no wish to wallow in the black plastic paddling pool. He has no regard for cats and would kill your cat Tenz if he could.

Dear Janice

There was a message on my answer phone at lunch time yesterday. It said, I can do tray of twelve, Mrs Pawsey. It was my friend, Pam. We call each other Mrs Pawsey and Mrs Ewart in March because we are both competing for the ribbon. The ribbon is the championship ribbon in the fruit and vegetable section of the Hawarden A&P show. It is awarded to the most outstanding entry and it is usually bestowed upon the collection of not more than twelve vegetables, although one year the ribbon was taken out by a lettuce.