Copyright 2003 by Joel Siegel.

Published in the United States by PublicAffairs,

a member of the Perseus Books Group.

All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address PublicAffairs, 250 West 57th Street, Suite 1321, New York NY 10107. PublicAffairs books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge MA 02142, or call (617) 252-5298.

Book design and composition by Mark McGarry, Texas Type & Book Works

Set in Fairfield

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data

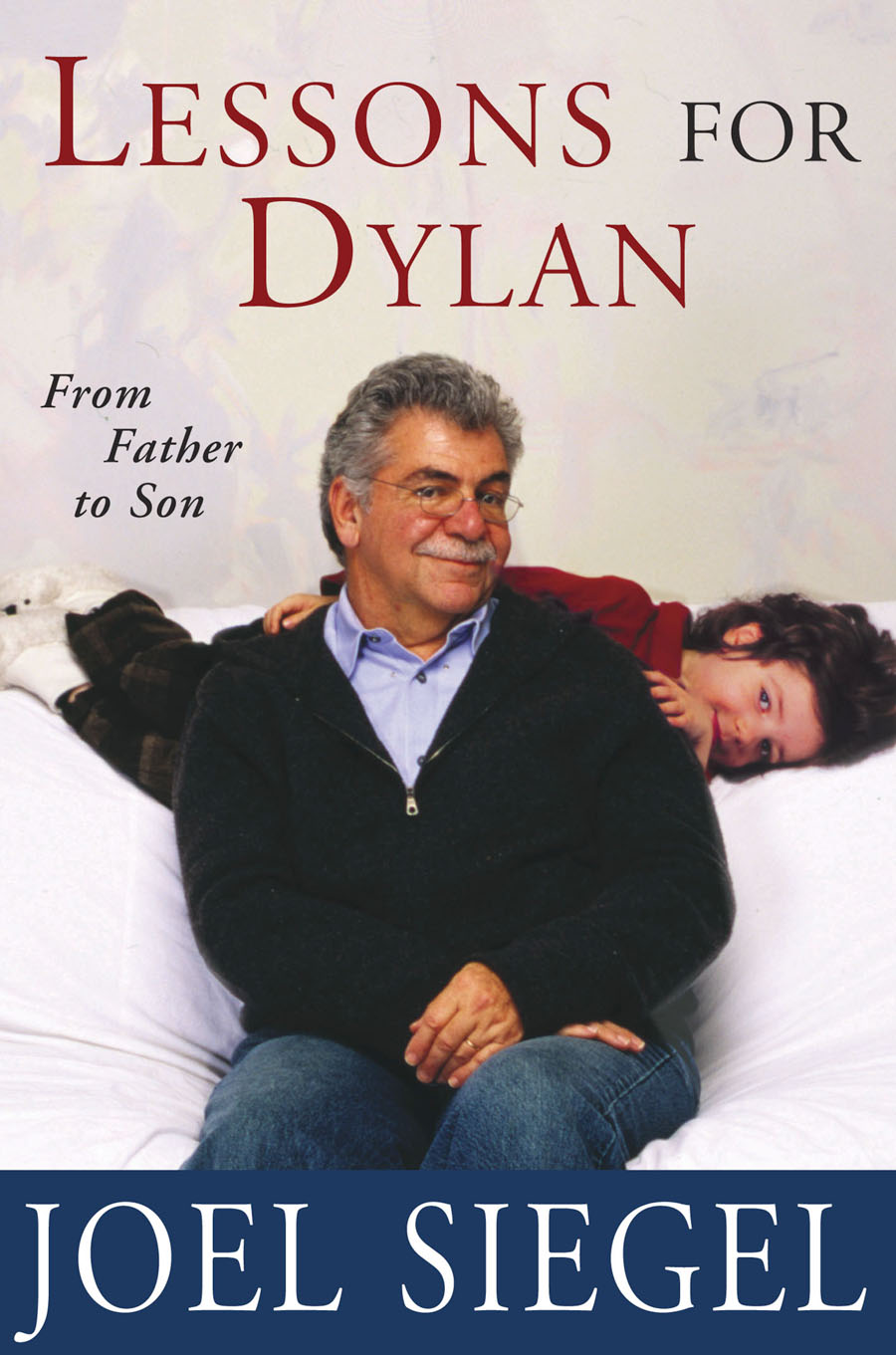

Siegel, Joel, 1943

Lessons for Dylan : from father to son / Joel Siegel.

p. cm. Includes index.

isbn: 978-0-7867-2369-0 (e-book)

1. Siegel, Joel, 1943 2. Film criticsUnited StatesBiography.

3. Conduct of life. I. Title.

pn1998.3.s495a3 2003 791.43092dc21

[b]

2003043168

to dylan

Of course

Contents

One morning while I was shaving, looking into the mirror, squinting through the soap and the steam, I thought about putting my glasses on, the better to see my face. Of course that is a dumb idea: Would I shave over or under the stems? And the steam that fogged the mirror would fog the lenses even worse. But I bet a couple of million guys have tried it. The thought made me smile. And, squinting the other way through the steam and the smoke, I saw my father smiling back. I knew it wasnt my memory of my father that was smiling back at meit was the part of my father that lives inside me.

My father has been gone for more than twenty years. I knew him pretty well; I was almost forty when he died. But my son, Dylan, may not get to know me. I was in my fifties when Dylan was born, so even in the best of times I couldnt expect more than a score or so of years with him. And it hasnt been the best of times, not with three cancer surgeries and chemo and CAT scans and six months of radiation in the past five years.

My doctors are optimistic, and, honestly, they have every reason to be. Not one of them has shown so much as a single symptom of anything even like cancer in the five years since my original diagnosis. I havent been that lucky. Thats why Im writing this book.

The book is not chronological. It begins with my fight against cancer because that is where my life with Dylan began. Dylan will have his own memories of some of those times; I want him to know mine.

In the book there are letters Ive written to Dylan, things Ive done I want to share with him, and a series of my side of the conversations Dylan and I might never get to have about things like college, drugs, baseball, even about his mom.

One of the unspeakable joys of watching your children grow up is watching them experience things for the first time. The first time we went to Disneyland, Dylan was three. His favorite thing about our trip was meeting Mickey Mouse. His second favorite was pulling leaves off a bush, dropping them, and watching them float to the ground. It was winter in New York, and when we left for Disneyland the trees there had been bare. A few months before, when there had been leaves on bushes and trees in New York, he hadnt been old enough, or his motor skills werent fine-tuned enough, or he couldnt reach high enough to accomplish this feat. He must have spent half an hour at the ice cream store on Main Street dropping leaves and watching them fall. He was more interested in the leaves than he was in the ice cream (this tendency must have been inherited from his moms side of the family). And I watched him discover that theyd float a little longer if he stood on his tiptoes and held his arm up as high as he could before he let the leaves go.

Ive written about some other things Id like to watch Dylan experience for the first time, some places I want to take him, some movies I want to watch him watch, some things I did with my dad that I want to do with him.

I know Dylan will take different things from these stories at different times in his life. Its taken me decades to understand the real meanings of things that have happened to me.

When I was about nine or ten and a smart-ass kid to boot, I asked my grandfather, my fathers father, why we Jews couldnt mix milk and meat.

Because it says in the Bible, Thou shalt not seethe a kid in its mothers milk, or something like that, was my grandfathers answer.

Now, I knew that answer. Id asked that question before, Id heard that answer before. But I didnt ask the question to learn the answer. The question was a trap. A setup. I told you I was a smart-ass kid.

OK, I pretended to puzzle out. But if its wrong to eat animals in their mothers milk, which does sound awfully cruel, why cant we eat chicken and milk? Chickens dont give milk.

My grandfather answered me the best way he knew how. He smacked me, hard, across the cheek with the back of his hand.

The lesson I learned that day was: Careful what you say to Grandpa, he might lose his temper and smack you across the head.

It took me forty years to figure out that the real lesson was: Never dis your grandfather by asking him a question he doesnt know the answer to.

I still havent figured out the answers to other questions life has forced me to ask myself. Like, why have I been married so many times?

Much of the time Dylan and I spend together we spend trying to make each other laugh. Playing hide-and-seek or being the monster or telling the most blatant, outrageous lies, especially about whether weve already eaten dessert, or sneaking up on me when Im reading the paperwhich, to Dylan, I must always seem to be doingand shooting it out of my hands with an explosive push and a huge, loud scream. Scares the hell out of me every time.

I asked Dylan if he could help come up with a title for this book. He thought for a second, then motioned me close with his finger.

I need to whisper it, he whispered.

I moved in to hear him and he shpritzed a Bronx cheer, a loud, wet PFFFFFFT! right into my ear, and laughed.

Hmm, I nodded, thoughtfully. Not bad, but how do you spell it?

He thought for a second and shpritzed me with four quicker, quieter Bronx cheers: Pfft, pfft, pfft, pfft. Not bad for four and a half years old. And I had no idea PFFFFFFT was a four-letter word.

I write about my triumphs so that Dylan will know the things I did well, and some flops so hell know the things I didnt do so well. And Ive tried to keep him laughing through both.

I dont think Dylan will mind my sharing our story with you. This is something I decided to do after we went public on Good Morning America and I received thousands of e-mails. Dylan and I arent the only parent and child who are afraid they may never get to know each other well enough, and my storytelling might help some of the others.

And, no, this isnt an autobiography; Ive left a lot out. It was never intended to be complete. After all, I have to save something for the sequel. What if I live?

Part 1

Dear Dylan,

They are words you dont easily forgetI dont have good news. Especially when theyre said by a doctor whos just finished giving you a colonoscopy.

It was the summer of 1997. One week before, wed had very good news. The in vitro had taken. Ena, your mother, my wife of one year, was now officially pregnant. The baby, thats you, Dylan, was due in February. The American Cancer Societys web site said that, all things considered, I had a 70 percent chance of being alive to witness the birth.