This edition is published by BORODINO BOOKS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books borodinobooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Borodino Books 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

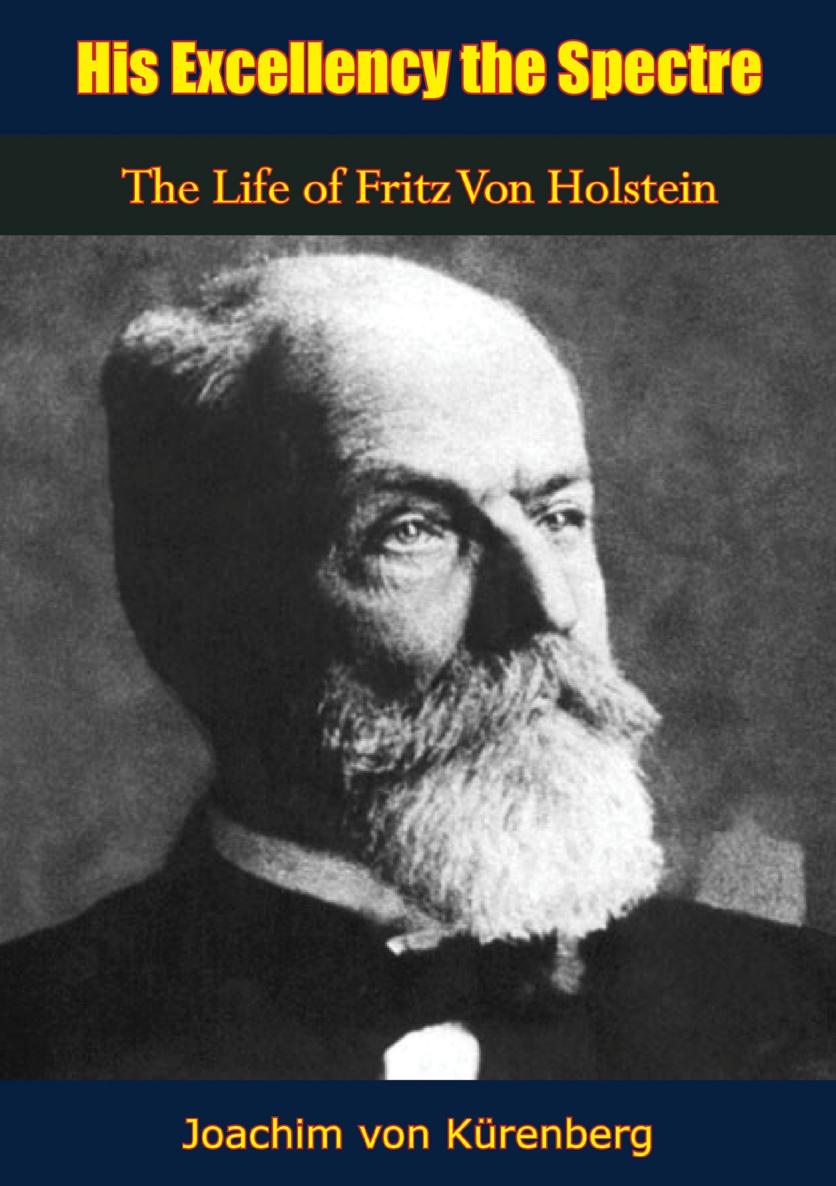

HIS EXCELLENCY THE SPECTRE

THE LIFE OF FRITZ VON HOLSTEIN

By

JOACHIM VON KRENBERG

Translated by E. O. LORIMER

With an Introduction by WICKHAM STEED

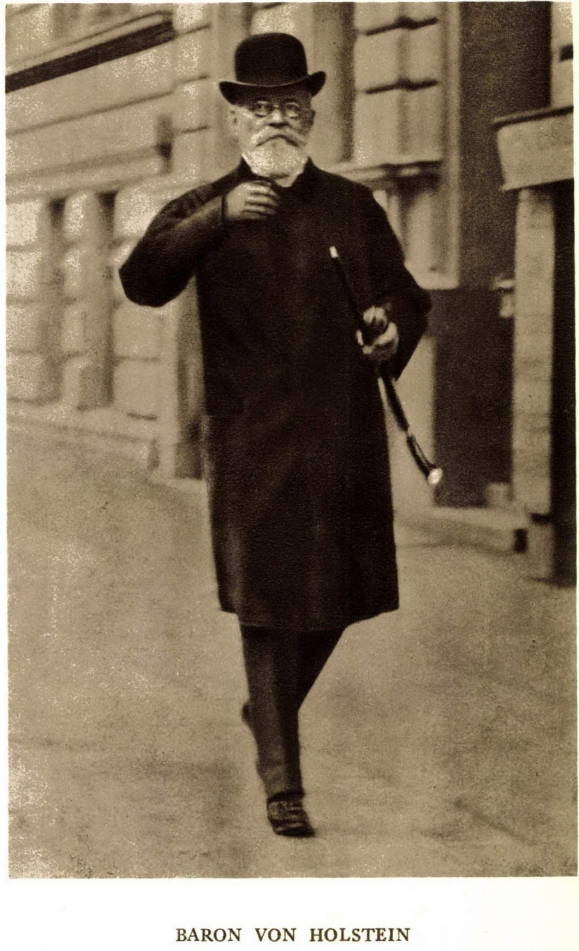

and a frontispiece in gravure

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PUBLICATION HISTORY

Joachim von Krenberg: Die Graue Eminenz

Der Lebensroman des Geheimrats Fritz von Holstein

Verlag fur Kulturpolitik G.m.B.H.

BERLIN, 1932.

Whoever first applied to Fritz von Holstein the nickname Die Graue Eminenz will certainly have had in mind the famous Capuchin friar, Pre Joseph, who was mentor, friend and me damne of Cardinal Richelieu, and was popularly known as Lminence Grise, in contradistinction to Lminence Rouge, his master. The parallel is not particularly fortunate, for Holstein owned no master save his own malevolent caprice and lust for power. It is hoped that the sinister suggestion which the German words convey, the hint of semi-invisibility and eerie menace, will equally be evoked by His Excellency the Spectre.

AUTHORS PREFACE

FOR close on forty years Baron Friedrich von Holstein exercised an immeasurable influence on Germanys foreign policy, but to the German people he was completely unknown. He lived the life of a hermit. He went nowhere. He took no public part in anything. He had no use for outward honours.

Bismarck, Caprivi, Hohenlohe, Blow, with one voice proclaimed him indispensable, yet he remains a legend to our generation. His contemporaries admired him, hated, feared him. They nicknamed him the Mole, Hyena-Eyes, His Excellency the Spectre. His policy may have been baleful, the means he used may not always have been fair according to our standards, yet no one can deny his great ability, his outstanding efficiency, his passionate love of country.

The Life Romance of Fritz von Holstein is based on historic events or episodes which took place in the circles surrounding the recluse, so selected as to throw his unique personality into relief.

Any attempt to record the whole course of the history that unrolled itself under Holsteins fingers would fill several bulky volumes and yet remain incomplete.

The authors aim has been, as far as possible, to bring the real man to life, to turn the spotlight on to Holsteins figure so that it may stand out against its background. He has therefore tried to render in seventy snapshots the kaleidoscopic play of historical events, and with the searchlight to illumine the darkness surrounding this best-hated figure of German foreign policy.

His history is the tragic story of a man condemned to work underground because he lacked self-confidence to face the light of day. Holstein remained averse from outward pomp, a lover of negation, a figure of night.

The words of the great Frederick, whose portrait stood ever on his desk, might have been written for him and may serve as his honourable epitaph:

Titles for fools, to decorate their fame:

A Great Man needs no title but his name.

INTRODUCTION

SOME ninety volumes, confidential talks with leading men of the Holstein era, and unpublished letters are cited as the sources of Joachim von Krenbergs work on the famous Eminence grise of the German Foreign Office. One hundred and ninety pages tell what the author calls the life-romance of Privy Councillor Fritz von Holstein. Many thick tomes, he says, could hardly record more than a fragment of German and international history as it was moulded by Holsteins hands. Therefore he has sought to sketch, in outline, seventy pictures to illustrate the life and work of this outstanding yet obscure servant of the German Empire who, time and again, governed it more truly than Bismarck, the Kaiser, Caprivi, Hohenlohe, or Blow.

If the method of picturing be open to question, its efficacy is beyond dispute. Holsteins figure stands out with a clearness which he might have been the first to deplore, for he lived and wrought in a penumbra, and was never more powerful or more dangerous than when wholly hidden from view. Has this clearness been attained at the cost of accuracy? Is the picture of Imperial Germany, which von Krenbergperhaps unwittinglypresents, true in substance? Are the sources, unspecified in detail though they be, trustworthy enough to warrant the conclusions he draws from them? Has he written history or merely a historical romance? For sundry episodes in his story no conscientious critic will go bail. They may be true, but they are not proven. Nor is it easy to verify all the alleged facts. Holstein dead is nearly as elusive as was Holstein living. I never met him, though I heard much of him from Sir Valentine Chirol and others who had known him. German diplomatists who worked under and feared him were apt to speak of him with bated breath. Maximilian Harden, who possessed his confidence and was used by him, could hardly be brought to mention him outside the pages of the redoubtable Zukunft . But, having read Die graue Eminenz with some care, I have sought corroboration for its assertions and suggestions in such of the sources as are within my reach. These researches incline me to look upon von Krenbergs pictures as truer to life than I expected to find them, and even to give him credit for truthfulness where proof or corroboration is lacking.

Here, in outline of an outline, is the Holstein story. A minor Prussian noble, born in an ancestral home in the Brandenburg Mark, Baron Friedrich von Holstein had, as a boy, seen his father trampled to death by sheep stampeding from a blazing barn. Later some mishap seems to have made him misanthropic and to have given his nature a womanish trend. Though not incapacitated for virile pursuits or lacking physical vigour, he never joined a students corps or held an officers commission. He was unmarried, and amorous adventures, if any, are unknown. Bismarck seems to have noticed him as a young, shy, awkward and secretive secretary of the St. Petersburg Embassy, and to have judged that he would be useful. Transferred to Paris, where Bismarcks opponent and potential rival, Count Harry von Arnim, was German Ambassador in the early seventies, Holstein was chosen by Bismarck to compass Arnims ruin. Telling Holstein that Arnim was subsidising an anti-Bismarckian journal in Berlin out of the secret service funds allotted to the Paris Embassy, Bismarck demanded that Holstein should get material proofs of Arnims misfeasance. In fact Bismarck ordered a subordinate to spy upon his immediate chief. In Bismarcks indictment there were four chief counts: (1) Arnims intrigues against Thiers and the French Republic; (2) his anti-Bismarckian view of the Old Catholic question; (3) his use of official information for financial speculation; and (4) his misappropriation of State funds to foster a newspaper campaign against Bismarck. Positive evidence in support of these counts was needed, and Holstein was told to get it by fair means or foul.