Praise

Within hours of the Twin Towers collapsing on 9/11, rookie news reporter Michael Petrou found himself launched on a decade-long journey through the conflicts of the Islamic World. Fresh from covering the rubble of New York, Petrou was to ride horseback into rugged Northern Afghanistan to cover the campaign against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in twenty-first centurys first new international war.

Few reporters make so abrupt a transfer from peace to war, and this was to be just the first of his many lone travels through conflicts of religion and ideology that now makes Is This Your First War? riveting and always insightful.

It is the remarkable personal story of a reporter who made the unlikely leap from being a newspaper intern to highly respected foreign correspondent within a few years due to sheer skill and willingness to take risks in the field. Along the way Michael Petrous keen ear for dialogue brings the stories of those trapped in a world of crisis richly alive for the reader.

BRIAN STEWART , VETERAN FOREIGN CORRESPONDENT AND DISTINGUISHED SENIOR FELLOW AT THE MUNK SCHOOL OF GLOBAL AFFAIRS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

Is This Your First War is a romp through time with a clever navigator at the information wheel. It takes the delightful roaming style of Rory Stewarts The Places in Between and travels from Tajiks and Ottawa editors to Chad, Iran, the West Bank and Afghanistan. The text is at times raw, making you feel like a voyeur who has slipped through the back door into a raging conflict. But the stories are witty and irreverent as well as deadly serious. If you want to know whats going on out there in the world and what its like to be a journalist on the front line of history, this is the book to read.

SALLY ARMSTRONG , AUTHOR OF BITTER ROOTS, TENDER SHOOTS: THE UNCERTAIN FATE OF AFGHANISTANS WOMEN

This book is a gritty, up close and personal chronicle of the great freedom struggle of our time. The world is rattling and humming from tremors that come from down deep, at the same tectonic level as the French Revolution. Is This Your First War? is a lively travelogue across a confounding terrain that goes by many names the War in Afghanistan, the Iranian uprising, the Arab Spring. When the world shakes like this, as it did during the Third World independence wars of the 1960s and 1970s, and during the collapse of the Soviet Empire, nobody knows what the landscape will end up looking like. But Petrou brings his readers deep into forbidding territory, across the front lines and back again, and journalism of the kind youll find in this book is indispensable to understanding the lay of the land. Besides, its a rollicking ride.

TERRY GLAVIN , AUTHOR OF COME FROM THE SHADOWS:

THE LONG AND LONELY STRUGGLE FOR PEACE IN AFGHANISTAN

IS THIS YOUR

FIRST WAR?

Travels Through the

Post-9/11 Islamic World

Michael Petrou

Prologue

T he first hint that B-52 bombers were circling overhead came from glints of sunlight. The lumbering planes were too high to be properly seen, but as they banked in their slow, graceful arcs, their silver wings caught the sun and sent it into our eyes as we sheltered in Northern Alliance trenches 10,000 metres below.

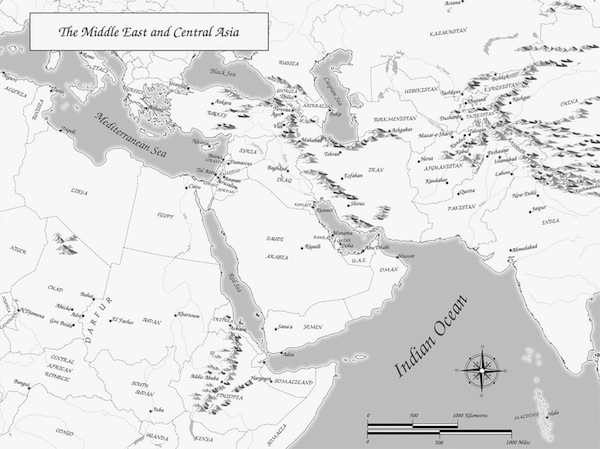

I had awoken that morning, in October 2001, on the ground inside a mud-walled compound run by the anti-Taliban Northern Alliance militia, who controlled a small corner of northeastern Afghanistan and whose fortunes were about to change because of those B-52s and the unseen Americans on the ground directing their bombs. Graham Uden, a British photographer with whom I was travelling, and I then hired a driver with access to one of the jeeps the Russians had left behind during an earlier war. We trundled westward out of Khodja Bahuddin, the small village where we slept, toward the front lines about 15 kilometres away. We passed below Ai-Khanoum, the ruins of a hilltop city once known as Alexandria on the Oxus, where Alexander the Great had established an outpost of his globe-spanning empire 2,300 years ago. Alexanders empire slowly disintegrated and his city on the Oxus was sacked, leaving pottery shards and marble column pediments scattered among the shell casings and gun emplacements of the Northern Alliance. When we reached the Kocha River, we left the jeep and hired horses from the wranglers who worked its banks. Their animals were skinny but strong, and while saddles could usually be found, none had stirrups, and my legs ached from hanging loosely against the horses flanks after a kilometre or two.

There were fewer and fewer people in the fields on either side of the dirt road on which we rode as we got closer to the front lines. Soon the cracks and sharp explosions of small arms could be heard, so different from the muffled rumble of airplane bombs that would occasionally reach us in Khodja Bahuddin. I stopped to talk to Abdul Haq, a lonely looking farmer, ethnically Uzbek, probably in his late teens, with a flat face and squished features. He wore one brown sock and one black and was hacking at the dirt below him with a hoe. He said that 300 people had left his village because of the fighting nearby. He left too but had nowhere else to go, so he returned with his mother. Then one morning as she dug at the very same dirt, she dropped dead, felled by a stray and almost spent bullet that came from so far away he couldnt see the shooter. A one-in-a-million chance. It is difficult to live here now, he said.

There was one more village before we reached the front lines, and this one really was deserted except for the holy warriors, as the local Northern Alliance commander said. They slept in the shells of buildings, the broken walls of which held belts of ammunition suspended from pegs and nails, and they had boiled tea over fires in houses with blown-off roofs. Enterprising boys from the village down the road brought bread. There were a few mortars set up among the ruins and a larger rocket battery behind the village. A hill rose above the buildings, treeless but with bits of green grass still clinging to its soil, and rolled toward the Taliban trenches visible on the horizon.

We climbed that hill, crouched over and bent at the waist, and then dropped into a trench as we neared its crest. The men and boys who manned that section of the front were happy to have company but warned us to keep our heads below the lip of the trench. Taliban snipers will get you, one said, and sure enough, when we did peek, tiny figures could be seen moving through their trenches about half a kilometre away. Until now the Taliban had been imagined more than seen, even when their bullets passed directly over our heads, and now there they were, just out of rifle range. Some were probably closer. I could have thrown a rock into the nearest Taliban trenches, but if they were occupied, the people in them were keeping their heads down, too.

The Northern Alliance fighters in the village below had fired off several mortars and a barrage of rockets as we arrived. Now the Taliban were shooting back. Their mortars were the most unnerving. There was a whooshing sound of rushing air as the small projectile shot in a high, looping arch toward us, and a second explosion when it hit. In between there was nothing to do but wait. I crouched lower in the trench and put my forearms on either side of my head. The Afghans said nothing until the impact bang sounded from a safe distance away and then passed around a bag of sunflower seeds.