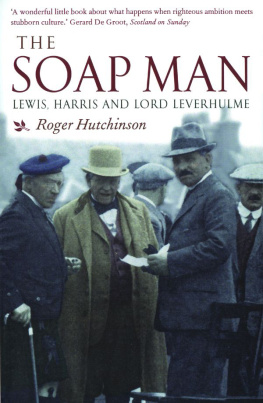

THE SOAP MAN

THE SOAP MAN

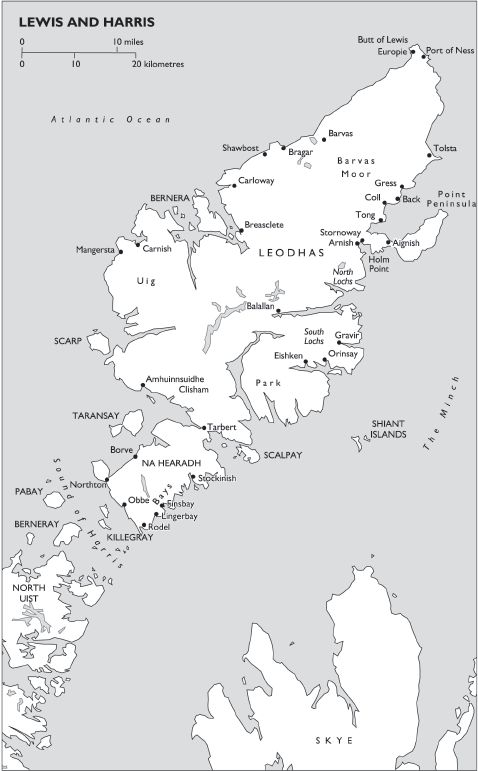

LEWIS, HARRIS AND

LORD LEVERHULME

Roger Hutchinson

This eBook edition published in 2011 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2003 by Birlinn Ltd

Copyright Roger Hutchinson 2003

The moral right of Roger Hutchinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-074-6

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

LIST OF PLATES

PREFACE

The Highlands and Islands of Scotland have seen a greater variety of landowning thugs, philanthropists, oafs and autocrats than any comparable region of the western world. Of them all, William, Viscount Leverhulme must be the most perplexing. He owned the largest single landmass in the Hebridean chain for less than a hundred months, yet in that short period he succeeded in dividing and confusing more intelligent people than seems possible.

To his family and his friends he was a good and simple soul brought low by Highland intransigence. To his acquaintances in Scottish government he became an irritant hardly to be borne. To the Gaelic Society of Inverness he was an English interloper trampling on a fragile heritage. To his fellow businessmen and directors of Lever Brothers he was an old but still formidable widower building castles in the sky. To the people of Lewis and Harris he was all of those things, occasionally at the same time, and ultimately another in a very long line of proprietors who could not bring themselves to understand the attachments and exigencies of their Hebridean lives.

Leverhulmes impact on Lewis and Harris in the first quarter of the twentieth century can still be felt today, and will resonate into the future. The period spent researching and writing this book coincided with the passage of a Land Reform Bill in Scotland. This piece of legislation offers to Highland crofters the right to purchase through their communities the land upon which they live and work.

For most Scottish crofters this represents an historical opportunity: their first chance to take control of their inherited home. Those in Lewis, however, might have enjoyed this privilege for more than eighty years, had their grandparents and their parents accepted an extraordinary offer made by Leverhulme during his brief period as their landlord. Some of them took advantage of this offer, and their democratically accountable landowning trust has subsequently stood for almost a century as a beacon on the bare northern hills. Others, for reasons which have previously been too often misrepresented, were obliged to decline. Only now are their descendants in western Lewis and in Harris able to reconsider the matter.

We may never understand the dead, but we can always try. The story of Lewis and Harris between between 1918 and 1925 was not only the story of a Lancashire industrialists twilight dream. It was also the legend of the men and women that he encountered at the end of the trail. Many people helped me towards a tentative comprehension of what happened in the northernmost Hebrides in those years, some without knowing it. I am indebted to them all, and especially to Joni Buchanan, Derek Cooper, Torcuil Crichton, James Hunter, Iain MacIver, Cailean Maclean, John MacLeod, Suisaidh MacNeill, Ian McCormack, John Murdo Morrison, Ishbel Murray, and Brian Wilson. All errors of fact and interpretation are, of course, mine.

It is the wish of every author of such a documentary as this to uncover an emblematic tale; one single anecdote as defined as a woodcut, that might stand forever as a metaphor of the whole tangled narrative. No such perfect item here exists, but one comes close. One of the medical officers for Lewis in Leverhulmes time, Dr Harley Williams, dined out for years on legends of the fall. He told a story which - unlike, I hope, most of what follows has been set in type at least twice before. Apocryphal or not, it bears a third rendering in the fresh light of what we now know of Viscount Leverhulmes character and motivations in the early 1920s, of the company he kept, and of the evidence before our eyes of the proud persistence of community life in the island of Lewis.

Leverhulme (said Williams) was one day visiting a rural village. An elderly woman standing at the door of her house noticed him, and wondered aloud: An e sin bodach an t-siabainn? Is that the old soap-man?

She is asking, explained the proprietors translator, Is that the Soap King?, my Lord.

Roger Hutchinson, Isle of Raasay, 2003

1

THE UNIVERSITY OF LIFE

Port Sunlight was the embodiment in bricks and mortar of the social and industrial philosophy of William Hesketh Lever. In 1887 it was an unpromising windswept area of marshland on the eastern coast of the Wirral peninsula, overlooking Liverpool and the broad Mersey estuary. In search of a new site for his expanding manufactory that year, Lever had boarded stopping trains up and down each bank of the Mersey from Warrington to the sea. He arrived at this reach of sodden fields and clutch of ramshackle shanties named Bromborough, turned to his companion and said: Here we are.

Thirty years later there were those who chuckled at Levers apparent naivety in buying for development 770 square miles of Hebridean bog and stone. They may not have been familiar with Bromborough in 1887. It was mostly, said one contemporary, but a few feet above high water level and liable at any time to be flooded by high tides and thus to become indistinguishable from the muddy foreshores of the Mersey. Moreover, an arm of Bromborough Pool spread in various directions through the village, filling the ravines with ooze and slime... it did not, at first sight, seem fitted for human settlement.

One year later, in 1888, William Levers wife Elizabeth cut the first wet sod out of the Bromborough turf, the shanties and cabins and the very placename itself were quietly removed, and Port Sunlight christened in honour of Levers celebrated brand of household soap slid optimistically onto the map. There were hard-headed business reasons for this relocation, insisted Lever characteristically at the banquet in Liverpool which followed the turf-cutting ceremony. Bromborough/Port Sunlight was beyond the grasp of Liverpools harbour dues, saving him four shillings and tenpence on every ton of tallow. The festering mire of Brom-borough Pool could be converted to an anchorage with straightforward access to the shoreside soapworks. And that very anchorage in the sheltered waters of the inner Mersey River would release Lever Brothers from their expensive dependence on rail haulage. He could export his cargo by ship to the grimy, soap-hungry hordes of late-Victorian London. That might teach the railways to become competitive, and William Lever was ever in favour of teaching others the necessity of competition.

What was more, Bromborough came cheap. Who else in their right mind would bid for such a waterlogged wasteland on the depressed southern outskirts of Birkenhead? He walked straight into a buyers market; into negotiations with local landowners who were delighted to exchange their unproductive swamp for a handsome handout from the

Next page