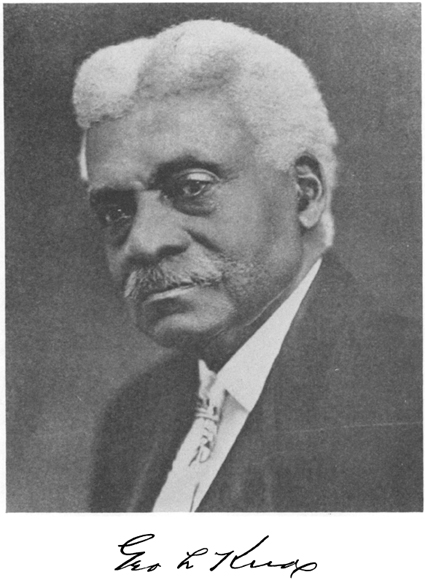

SLAVE AND FREEMAN

SLAVE AND FREEMAN

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

GEORGE L. KNOX

Edited with an Introduction by

WILLARD B. GATEWOOD, Jr.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Knox, George L 1841-1927.

Slave and freeman, the autobiography of George L. Knox.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Knox, George L., 1841-1927. 2. Afro-AmericansIndianaBiography. I. Gatewood, William B. II. Title.

F535.N4K557 977.200496073 [B] 78-21058

ISBN 978-0-8131-5222-6

Copyright 1979 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky,

Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Club,

Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society,

Kentucky State University, Morehead State University,

Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University,

Transylvania University, University of Kentucky,

University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40506

CONTENTS

From Slavery to Freedom:

Tennessee, 1841-1864

Citizen of Indiana:

Small-Town Barber and Politician, 1864-1884

Foremost Black Citizen of Indiana:

Indianapolis, 1884-1894

To

VICTORIA KNOX PORTER

granddaughter of George L. Knox

PREFACE

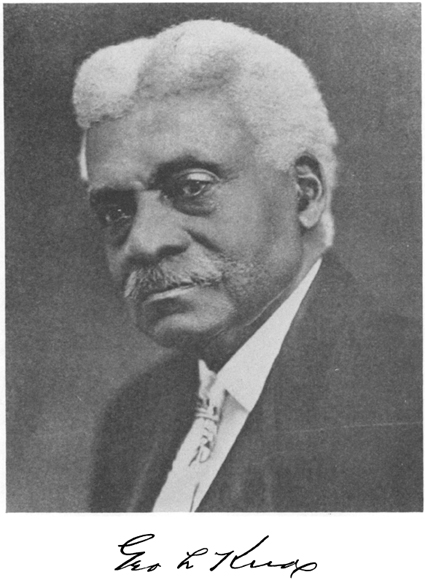

By the 1890s George L. Knox was generally recognized as the most prominent black citizen in Indiana. Born a slave in Tennessee, he migrated to Indiana shortly before the end of the Civil War and settled in Greenfield where he embarked upon a career as a barber. In time he expanded his barbershop, purchased real estate, participated in local politics, and acquired a wide circle of acquaintances, including the poet James Whitcomb Riley. After eighteen years in Greenfield, Knox moved to Indianapolis where he resided from 1884 until his death in 1927. In Indianapolis he operated a large and well-equipped barbershop in the heart of the city. A conspicuously successful black businessman closely identified with a variety of religious, civic, and racial organizations, he was best known, perhaps, as the owner and publisher of an influential black newspaper and as an active member of the state organization of the Republican party. Throughout his life Knox consistently maintained that only through work, thrift, personal morality, and self-help would black Americans succeed in their struggle for first-class citizenship. Convinced that his own career provided abundant evidence in support of the validity of such a formula, he decided to publish his autobiography in serialized form in the weekly editions of his newspaper.

Ultimately his success story appeared in fifty-four chapters, ranging in length from a few brief paragraphs to several columns set in small type. On occasion the availability of space in a particular edition of his paper obviously dictated chapter lengths. It also appears that each installment of the autobiography was published as soon as Knox had written it. As a result, in two instances when he later recalled experiences which he considered significant but which had been omitted from the narrative already published, he incorporated them into two chapters and allowed these chapters to appear out of chronological sequence. For the sake of clarity and continuity, the edited version of the autobiography has abandoned the numerous and often meaningless chapter divisions and instead has been divided into three sections, each of which encompasses an important segment of Knoxs career. The material contained in the two chapters which originally appeared out of sequence has been inserted at chronologically appropriate points in the narrative. Throughout, an effort has been made to identify individuals, incidents, and institutions mentioned in the text of the autobiography. The introduction, which attempts to place Knox in historical perspective, devotes especial attention to his career during the period after 1894 which is not covered in the autobiography.

Numerous individuals provided valuable assistance in the editing of this work. I am especially indebted to librarians and archivists at Indiana State Library, Ohio Historical Society, University of Arkansas, and Duke University. Various officials of Wilson County, Tennessee, made it possible for me to consult important records in the courthouse in Lebanon. Nan Woodruff of the Booker T. Washington Papers was extraordinarily helpful in ferreting out the Washington-Knox correspondence. Two of my colleagues, James S. Chase and Randall B. Woods, read the manuscript and gave me the benefit of their counsel. John Hope Franklin not only offered perceptive suggestions and criticisms regarding the manuscript but also located various members of the Knox family. My debt to him is immeasurable. Knoxs great-granddaughter, Sister Francesca Thompson, OSF, offered encouragement and graciously responded to my numerous inquiries. Barbara Lineberger, who typed and retyped the manuscript displayed extraordinary patience and an uncanny ability to decipher my copy. My wife, Lu Brown Gatewood, maintained a constant interest in this project and is in large measure responsible for its completion.

W. B. G.

INTRODUCTION

AT THE AGE OF FIFTY-FOUR GEORGE L. KNOX, THE PREEMinent black citizen of Indiana, decided to publish his autobiography. For a year beginning in December 1894, virtually every issue of his weekly newspaper, the Indianapolis Freeman, included one or more chapters of his Life as I Remember ItAs a Slave and Freeman. Although Knox indicated that the account of his life would appear in book form shortly after its serialization in the Freeman, no such volume was published. He may have been discouraged by the unflattering references to the account, which appeared in a few black journals, Again, for reasons unknown, an autobiographical volume failed to appear. Since Knox remained an active force in Afro-American life for more than three decades after the publication of his life story in the Freeman in 1894-1895, it is unfortunate that these decades are not covered in his extant writings. Clearly, however, that portion of his autobiography which does survive was written at a time when he had reached the pinnacle of his prestige and influence. Between 1888 and 1896 he acquired substantial wealth, purchased a newspaper, and served twice as a lay delegate to the General Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church and twice as an alternate delegate-at-large from Indiana to the Republican National Convention. Prominent in numerous civic and racial uplift organizations within the black community, he counted among his friends and acquaintances a host of famous Americans of both races, including businessmen, bishops, senators, poets, and a president of the United States.

On September 18, 1895, several months before the appearance of the last installment of Knoxs autobiography, Booker T. Washington delivered the famous address in Atlanta which thrust him and his formula for race relations into national prominence. Knoxs autobiography and Washingtons address had much in common. Although the two men differed in educational background, religious concerns, and techniques of political involvement, their ideological assumptions and outlook on racial matters were almost identical. Both exuded optimism even in the face of devastating adversity and persisted in the belief that self-help, personal morality, industry, the acquisition of property, and adjustment to a segregated society constituted the only feasible means for black Americans to advance. As former slaves whose successes were of the Horatio Alger variety, both found in their careers justification for their formulas of racial progress. That blacks could overcome the prejudice against their race through productive, upright lives was a theme that pervaded Knoxs autobiography as well as Washingtons Atlanta Address and his