Before first light, young Morris Kafitz hitched up the horse and wagon and set out along the lanes of Georgetown. The gas lamps were still lit, and the reflections flickered off the cobblestones. As he rode south along Twenty-seventh Street, beneath a canopy of trees, the clopping echoed between the facing rows of houses.

Morris was accustomed to the early hour. He had a sturdy build and a strong and stolid face, with dark hair and somber blue eyes that kept their own counsel. As the eldest of the three sons, he woke each morning at four thirty and made his way across the sleepy, shuffling city of Washington, in the District of Columbia, to buy fresh produce at the Center Market and sometimes to shop for fish down at the wharf. Only after hauling these provisions back to his fathers grocery store, at Twenty-seventh and O Streets, in the citys northwestern quadrant, would he rush the three and a half blocks to the Corcoran School, with its redbrick Romanesque tower.

Soon his schooling would end, after the 19012 school year, once he had finished the seventh grade at age fourteen. What Morris wanted for himself in this land of liberty was not found in books.

Surely there was no shame in living in unfashionable Georgetown, even in its shabbier eastern end. This was paradise compared to Lithuania. His family had fled the pogroms when he was eleven and by 1898 had wound up in Washington, where some cousins had settled. The seven of them, Nussen, Anna, and the five children, lived first in a shack twenty-some blocks north of the Capitol building, and then in an alleyway a dozen blocks closer.

Pierre LEnfants grandiose design for the nations capital, with its broad avenues and elongated blocks, had created a web of alleys, out of sight, where freed slaves lived after the Civil War. The Kafitzes were among the few white residents on Glick Alley, a dirty, overcrowded lane that stretched from S Street NW to Rhode Island Avenue, between Sixth and Seventh Streets. They occupied a two-story, four-room tin-roofed brick house, all of fourteen feet wide, dark and damp, without a basement. A spigot and a privy stood in the back.

Nussen was known as Nelson or Nathan in his new country. He was a small dapper man with a round fragile face and a trimmed beard. He had a sparkleinto his eighties he would chase his second wife around a tableand a sense of humor and no desire to speak or write in English. He opened a grocery on Glick Alley, in one of the ground-floor rooms. This was the most common business for the citys immigrant Jews, because it required little money or know-how.

Within a year the Kafitzes had left the alley and moved to Georgetown. They could afford to live away from the grocery, though the row house at 2706 N Street was even narrower than the house on Glick Alley and also lacked indoor plumbing, a hardship for the children on winter nights. Most of their neighbors were coloredteamsters, servants, a porter, a deliveryman, a dressmaker, a day laborer, a washer-woman, an ash man, a laborer for the federal Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Georgetown was a quilt of black and white, of the poor and the poorer.

Forty-nine years older than the city of Washington, Georgetown had been named not for that George (though he had slept there many a night, a half-days ride from Mount Vernon) but rather for Britains King George II, whose governor of the Virginia colony had dispatched that George as a young colonel out to Ohio, an excursion that touched off the French and Indian War. The village, near the head of the navigable Potomac River, had originally been a thriving port for Maryland tobacco and then a point of departure for trade with the Ohio River Valley. Even after the capital was founded, in 1800, the handsome brick town houses and bustling streets of Georgetown outshined the drab and sparsely settled city next door, as a residence for foreign diplomats and the more adventurous members of Congress. Georgetown had ceased being a separate municipality within D.C. in 1871, and its social standing had withered. A port once a forest of masts had become an industrial suburb for a city lacking much industry of its own. The riverbank now harbored iron foundries, lime kilns, a sheet metal works, a bottling company, a coal yard, an electric powerhouse, andworst of all, to the residentsan animal rendering plant, with its reek of decay. Only people who had few choices lived nearby.

Morris rode ahead toward M Street. On his left, past a prim Baptist church, an open field gave way to the ravine, dense with trees, that cradled Rock Creek. He turned left onto M Street, still known to many as Bridge Street for the iron-laced bridge that crossed the creek. He trotted above the mouth of the wide, rushing stream and into what had been properly known until recently as Washington City. Two quick turns put him on Pennsylvania Avenue, as broad a boulevard as any in the capital.

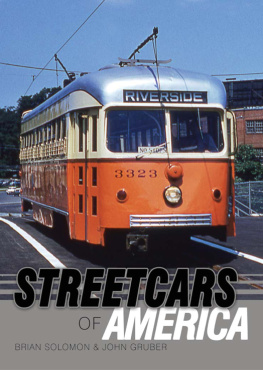

The scattered buildings stood low in the lightening sky. It was quiet here, and spacious. The paving of asphalt and coal tar climbed steadily before him, a godsend for the ever-more-popular safety bicycles. His horse sidestepped the slots for the streetcars. Morris liked to race the electrified streetcars, though once while doing so he had spilled a wagonful of groceriesoranges and everythingall over the road.

Washington was an unhurried city of barely a quarter-million inhabitants, ranked fifteenth in the nation, just behind Milwaukee. When they say noon in New York it generally means a little before; when they say noon in Washington it always means from one to four hours later, a longtime Washingtonian explained. It was a southern city, of azaleas and magnolias, where people used proper manners and spoke softly (reckonyou-all) in Tidewater accents. Most of the newcomers had moved there from Virginia or the Carolinas, accounting for the grits that people served with breakfast. The city moved at a leisurely pace. Men moved languorously on the streets, wearing broad-brimmed felt hats and Prince Albert coats. The vines, luxuriant in the steamy summertime, climbed any available wall. Washington was a green city, and a clean one, because of the sparse industry and the paucity of smoke.

Poplars lined Pennsylvania Avenue, as if guarding the clusters of row houses with elegantly rounded corners or elaborate cornices or half-moon windows and exuberantly pointed roofs that were only for show. Morris glimpsed a corner of the rambling red buildings belonging to the Columbia Hospital for Women and then passed Saint Anns Infant Asylum. Ahead was Washington Circle, where Pennsylvania Avenue crossed K and Twenty-third Streets. Inside the circle, gas lamps and benches on curving paths surrounded a statue of General Washington on horseback, triumphant at the Battle of Princeton.

The streets grew busier as Morris approached the capitals monumental core. At Twenty-second Street he passed the Six Buildings, century-old town houses in the unadorned Federal style where James Madison and later Sam Houston had lived, and three blocks farther, the Seven Buildings, the capitals original Diplomatic Rownot that Morris knew or cared. Three-or four-story row houses lined both sides of the avenue, many with shops on the ground floor. At Eighteenth Street, a coal yard stood across the avenue from a hardware store, a dairy, a steam laundry, and a bicycle repair shop.

At Seventeenth Street, to the right, rose the citys most fantastical building, housing the governments gravest responsibilities. Nine hundred columns, flamboyant chimneys, and mansard roofs of dramatic proportions lent the State, War, and Navy Building an unembarrassed ostentation, revered by many and reviled by more. (Its architect committed suicide two years after it was finished.) Just beyond it, set back from the avenue, behind an expanse of lawn, stood its antithesis, a marvel of unforced dignity. Only recently had the brash young Teddy Roosevelt, in one of his earliest acts after President William McKinleys assassination in Buffalo, officially named it the White House. There was talk of adding east and west wings to the Executive Mansion, so he might escape his six rambunctious children while attending to affairs of state, though he was thinking he would rather keep living at the White House but move his offices someplace else. As it was, an ordinary citizen could stroll unhindered through the open gates and leave a calling card on a silver tray for the president, who was no longer merely the leader of a provincial democracy but of an emerging world power.