Acknowledgments

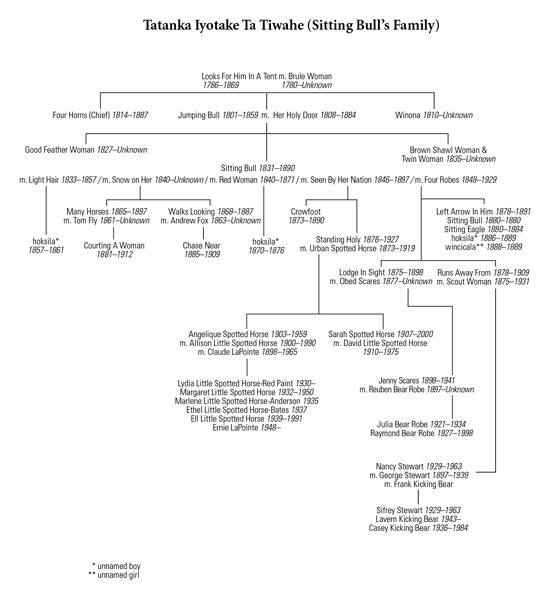

The following individuals and institutions were graciously kind and generous with their time and knowledge: My late mother Angelique Spotted Horse-LaPointe, my granduncles John Sitting Bull (Refuses Them) and Henry Little Soldier for their oral stories which I wrote down in this book; my sister Marlene Andersen for refreshing my memory; Serle Chapman, a great writer of the real West, who seeks the truth and who provided me with the original photographs; Lani Van Eck, my contributing editor, who persuaded me to put my oral history into book form; Bill Billeck of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who allowed me to publish parts of the report on the repatriation of the lock of hair and the leggings of my great-grandfather; Bill Matson, my friend the moviemaker, who stood behind me with his encouragement during the filming of our DVDs and through the writing times of this book; Bess Edwards, the grandniece of Annie Oakley (Little Sure Shot), who shared a story with me that I included in this book, and I cherish her friendship; Sion Hanson, the great-grandnephew of James Hanson, for sharing his story with me; Sharon Small, curator at the Little Bighorn Battlefield Museum; John Doerner, historian at the Little Bighorn Battlefield; Carol Bainbridge, director at the Fort St. Joseph Museum in Niles, Michigan; the Library of Congress; the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Canada; Ken Woody and Michael Bad Hand Terry, who introduced me to Gibbs Smith. A special thank you to Gibbs, for the royal treatment you gave me. To Michelle Branson, my editor, thanks for your patience. And a big thanks to all the staff at Gibbs Smith. Finally, to my wife Sonja, for creating the family tree, and finding all the documents, legal papers, and official letters to back up my oral story.

Pilamaya Yelo (thank you) to everyone who touched my life and gave me inspiration and direction.

Ernie LaPointe

Foreword

This is Ernies story of the life of his great-grandfather. He was initially hesitant about putting this oral history into written form. It was only after long consideration and much urging by a number of people (including me) that he agreed. The most convincing argument I could make was based on the durability of this medium. Books have been a continuous part of human life for thousands of years. Written records last.

In many ways, this is not a conventional biography. Instead, it is a written form of oral history, with all the advantages and difficulties that entails. Oral tradition operates within its own framework of conventions and rhythms, not all of which translate readily. A spoken narrative can make use of a number of dramatic devices that are not available in written form.

Speaking allows the narrator to set a pace, to develop a cadence that carries the listener forward into the action of the story. Altering the tempo subtly creates mood, quickening with excitement or slowing with comfort. Inflection expresses emotional content without the need for further explanation. Tonality trumpets defiance or whispers humility.

Body language comes into play as well. In the Lakota oral tradition, stories are told face to face. The narrator can focus attention on his words through his bodys stillness or, through his gestures, enhance and expand the scope of what is communicated. A master of the oral traditionand Ernie is such a masteris a true performance artist who holds his audience in thrall.

Oral tradition also differs from standard written biography in content. The conventional biography relies on a chronological unfolding of the major events within the lifetime of its subject. Considerable effort is expended in creating an overview and weaving the life of the chronicled individual into this context. Cause and effect, stimulus and response become criteria by which the main character is evaluated, explained, and ultimately judged.

In oral history, the intent is subtly different. Chronology is not as important a consideration, and little attention is devoted to detailing every moment. Instead, the narrative is episodic in its focus, and each episode has a point . There are morals to these stories. They are intensely value-laden. Ultimately, a standard biography may convey to its reader a carefully woven tapestry, where each thread is tightly and precisely placed to ensure its accuracy in the overall presentation of a factual picture. An oral history, on the other hand, is more analogous to a well-constructed quilt whose patches of vibrant color work together to create a warm impressionistic pattern.

One of the challenges in writing this book was to merge the two, confining the flow of the spoken narrative within the structure of the written form. Ernie was adamant that nothing be included in this book that is not absolutely and strictly the truth as he knows it and has personally experienced it. This raises the second major complication in creating this written narrative. The truth that Ernie seeks to impart in this work is a Lakota truth.

Ernie is a truly bilingual individual. However, there are still translation problems that arise between Lakota and English. The issue here is conceptual, a question of very different world views. The Lakota perspective on the universe and our human place in it is unlike the beliefs espoused by the surrounding culture of the United States. The distinctions are fundamental and mold the shape of the entire culture.

The understandings of the nature of our being and the purpose of our existence are deeply ingrained in all of us, taught to us from the beginning of our awareness. They form the focal point for our most basic assumptions about life and how we should interact with others. What are worthy goals, and how should we define success?

In the culture of the United States, we are taught to cherish our inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. These, however, are cultural values which, while critical to our society, may well be subordinate to other values in other cultures. As an example, I could not begin to enumerate the number of times I have heard Ernie stress the values of honor, respect, humbleness, and compassion. When you read this book, you will encounter these core values repeatedly. If you are also a member of the Lakota culture, these values have probably resonated for you at a deeply personal level.