Contents

Guide

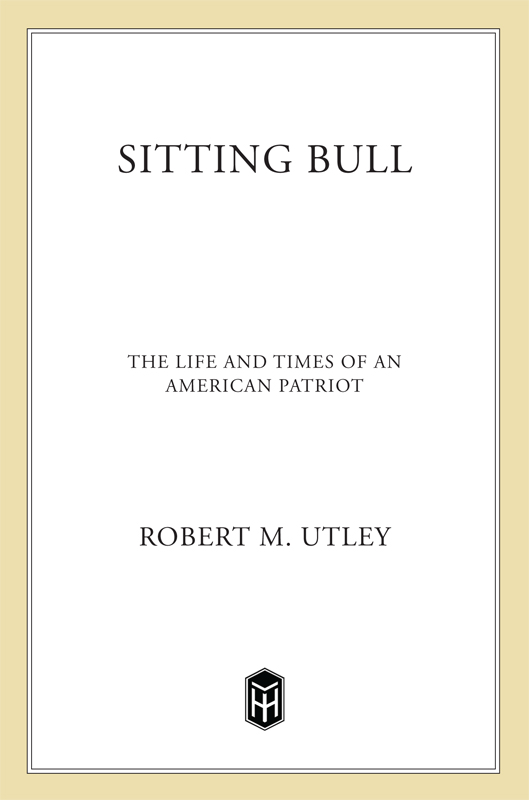

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

For sons Don and Phil

and daughter-in-law Susan

PREFACE

THE DEATH OF Sitting Bull, followed by the tragic clash at Wounded Knee Creek, was not, as the title of my first book (1963) declared, The Last Days of the Sioux Nation. On the contrary, after 1890 the Sioux went on adapting, doing what they had been for centuries. For example, the advent of the horse years earlier converted them from pedestrians into mounted nomads, with consequent cultural changes of huge magnitude.

Yet the killing of Sitting Bull, combined with Wounded Knee, symbolized the death of another concept, the one that had rationalized the westward movement of white Americans for more than half a century. Manifest Destiny, first articulated in 1845, held that the Christian God had commanded his people to overspread the earth and make it blossom. Heeding the providential destiny so clearly manifest, white Americans did just that, with varying degrees of success.

The travails that the patriot Sitting Bull and the statesman Red Cloud endured in the decade ending in 1890 stamped the Indian reservation system as a permanent fixture on the American landscape. On the continent at least, Manifest Destiny had triumphed. (It would once more find expression beyond the United States in the Spanish-American War at the turn of the century.) Indians had been effectively imprisoned on reservations or destroyed. Beyond the reservation boundaries, land once their homeland no longer belonged to them. By 1890, the U.S. superintendent of the census could no longer trace a frontier of settlement on the map of the American West, upon which historian Frederick Jackson Turner had built his thesis that the westward movement was the template that had molded the American character (it was a thesis that reigned in academic circles until rejected by modern historians).

After 1890, even as the remnant Indian tribes adapted, they lost none of their spiritual ties to the homeland of which they had recently been deprived. Even Indians who had left the reservation, many to find new lives in cities (and outwardly adopted forms of the dominant culture) retained spiritual bonds to homelands some may never have seen. Wherever they lived, resentment of the consequences imposed by United States policies, cloaked in the rhetoric of Manifest Destiny, persists to this day. For the Sioux, memory of the death of Sitting Bull and of Wounded Knee burns brightly and fuels their resentment. It even finds expression in todays controversies over the final resting place of Sitting Bulls bones and in annual ceremonies at Wounded Knee Creek.

To the Sioux, Sitting Bull is still the preeminent patriot who remained steadfastly wedded to the old ways and old homeland to his dying day. More than stoking resentment, more than a shining but doomed patriot, Sitting Bull symbolizes a treasured but lost way of life for all Indians, spiritually, politically, socially, and economically.

* * *

FOR MORE THAN a century, the standard biography was Stanley Vestals Sitting Bull, Champion of the Sioux. Other portraits have come and gone, but most have been superficial or worse.

Perhaps it seems in poor taste to use Vestals own research to challenge the domination of his biography. But my book and his are of very different characters.

In preparation for his book, Vestal conducted exhaustive interviews with elderly Indians on the Sioux reservations of North and South Dakota. His field trips occurred in the late 1920s and early 1930s, when the young men of Sitting Bulls time were in their seventies and eighties but still mentally alert. He won the confidence of Sitting Bulls family and associates while they could still recount their experiences and impressions. In particular, White Bull and One Bull, Sitting Bulls nephews, were indispensable. Vestals papers at the University of Oklahoma Library in Norman are invaluable, although recorded in an invented shorthand almost impossible to decipher without extensive background knowledge. Neither his book nor mine could have been written without them.

Vestals biography is another matter. His Sitting Bull and mine are essentially the same person. We reached our destination, however, by different routes. He built his character more by literary than historical method. Mine is built by historical method.

The Vestal genre is not unique. He was one of a trio of scholars who presented themselves as historians but viewed the Sioux mainly through literary lenses. The other two were Mari Sandoz, biographer of Crazy Horse, and John G. Neihardt, author of the classic Black Elk Speaks. Like Vestal, they achieved ultimate truth in works that are good literature but bad history.

Vestals interpretations of Sitting Bull came as a shock to many Indians and whites identified with his final years. They remembered him as a disgruntled troublemaker, obstinate, conceited, narrow-minded, obstructionist, a physical and moral coward, and pretender to high rank and power that had never existed. Some, such as missionary Thomas L. Riggs, complained that White Bull and One Bull, and others of Sitting Bulls clique, had duped Vestal by portraying a sainted but fictional forebear.

In fact, James McLaughlin, Sitting Bulls Indian agent during the reservation years, duped everyone, white and Indian alike. Finding Sitting Bull unpliable, too much the Indian of old to lend his influence to government programs for transforming his people into imitation whites, McLaughlin created the false portrait that dominated thoughts about Sitting Bull until Vestal reshaped it more truthfully. I have discovered enough persuasive evidence in other sources to corroborate the essence of the image recalled for Vestal by White Bull, One Bull, and other Indians of the 1920s.

It is exceedingly difficult to write the biography of a person of another culture, especially one that in its essentials no longer exists. I have tried to look at Sitting Bull in terms of his cultural norms, not mine. Where whites drew false conclusions because of ignorance of his culture, I have sought to stress his rational underlying motives. Where I could not fathom his motives, I have tried to avoid judgments according to my culture when his, if only better understood, might have supplied a logical explanation. Yet Sitting Bulls claim to significance beyond his own tribe rests on his role in the collision of two cultures, and I have therefore tried to view him from the white as well as the Indian perspective.

From both, he emerges as an enduring legend and a historical icon, but above all as a truly great human being.

Georgetown, Texas

August 2007

PROLOGUE

THE WHITE BUFFALO WOMAN gave the Lakotas the Sacred Calf Pipe and with it all that made life meaningful. The people had wandered the earth for countless generations, ever since emerging from the underworld in misty antiquity. Not until the wondrous appearance of the White Buffalo Woman, however, were they truly Lakotas. There was nothing sacred before the pipe came, explained Left Heron. There was no social organization and the people ran around the prairie like so many wild animals.