This edition is published by Muriwai Books www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books muriwaibooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1927 under the same title.

Muriwai Books 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

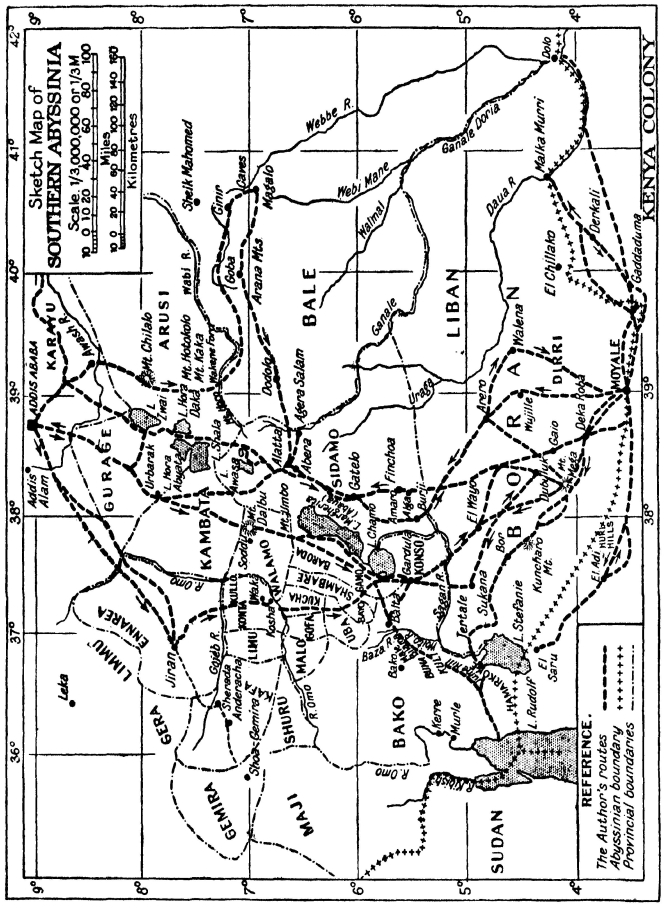

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

SEVEN YEARS IN SOUTHERN ABYSSINIA

BY

ARNOLD WIENHOLT HODSON

C.M.G., F.R.G.S., One of His Britannic Majestys Consuls for Ethiopia 1914-1927

Edited by C. LEONARD LEESE

CHAPTER IABYSSINIA AND ITS PEOPLE

Journey outAbyssinian seals and lettersimpressions of the capitalthe building of modern AbyssiniaTheodore and MenelikAbyssinian titlesracial, religious, and linguistic divisions.

JUST after the outbreak of war in 1914 when stationed with my regiment in Norfolk, I was appointed to the new post of British Consul for Southern Ethiopia. I applied for special permission to remain with my regiment but was refused. In consequence I sailed for East Africa via the Cape when the issue on the Marne was still hanging in the balance. The hopes and fears of all our ships company were fixed on Europe, and it was difficult even for a newly-fledged Consul to devote himself as much as he might have done to the acquiring of book-knowledge about the country for which he was bound. The inevitable crop of war rumours and the daily quarrels among the amateur strategists which these inspired relieved the tedium of the voyage. Mombassa, however, was reached without serious incident. Havingfortunatelyno reason for remaining on the coast, I proceeded at once by train to Nairobi, the capital of the East Africa Protectorate, or Kenya Colony, as it is now styled. A fortnight in this delightfully sociable town passed all too quickly. I received my instructions from the Governor, picked up from officials and others many and conflicting accounts of the kind of life that was in store for me, and at last on 4 th November set out on the final stage of my journey to Abyssinia.

My route from Nairobi lay northward to Archers Post and then down the Uaso Nyro River to the Lorian Swamp. From there the road ran to Wajir, and after that into the administrative area known as the Northern Frontier District. Owing to the War it was not an easy matter to arrange for the transport of my supplies. When I reached Archers Post, I received a letter from the officials stationed at Marsabit to the effect that they had only been able to get for me two police and three men, Somalis, to act as my guard to Moyale, and that these were probably bad characters, as they knew nothing about them. These men were to go right through with me, and in addition I was provided with carriers from post to post. When I left Archers Post, I must have had about a hundred carriers, fine men from Meru, and the journey went as smoothly as possible till we reached a place near the edge of the Lorian Swamp, called, I think, Arodima, where I had to turn off to go to Wajir. Here the Meru porters had to return, and henceforth I was dependent on camels. As I was left with only the few men referred to above, the various Somali headmen living at this place concluded that I was very small beer, and their attitude showed it. Numbers of them came with goats and sheep, which they offered as presents. I said I did not want them, as I knew they expected twice their value in return and it would have been cheaper to buy them. At last, however, as they insisted, I took two of the animals, put them in a kraal, thanked the donors profusely, and went away, giving nothing in return. The stream of people bringing presents at once ceased, the queue vanished, so also very shortly afterwards did the two presentation goats I had placed in the kraal.

Arodima was a desolate and depressing spot, and to my annoyance I had to wait here several days while camels were being procured. A plausible Somali with whom I got into conversation whetted my appetite for sport with a tale of a wonderful elephant carrying the biggest tusks known to man. The country all around consists of dense thorn bush, and into this country I went with the optimistic Somali and one of my servants. We toiled the whole of one day, slept the night in the bush, and then toiled back without seeing any sign whatever of big game.

Shortly after leaving Archers Post, when out-spanned at one of our camps, my only mule was grazing with one of its legs attached to a long rope tied to a tree. Now this mule had an innocent face, had behaved extremely well from Nairobi, and had given me the impression that if I let it loose for a short time it would play the gamehave a roll, enjoy the succulent grass at its leisure, and not run away. I had not then lived eight years with mules as I have since. The boys protested and said it was a mistake. I overruled their objections with harsh words, and the mule was released. I still believe it winked at me as it put up its tail and cantered away. I did not see that mule again for three years, and bitterly did I repent my folly as I tramped along day after day in the sun.

After a great deal of trouble, the necessary camels, twenty-five or thereabouts, were obtained, and one afternoon everything was at last loaded up and we started. Loading all these camels with the few men I had was a big undertaking, and it was therefore necessary to make as long treks as possible in order to minimise the delay and trouble caused by loading and unloading. I saw the caravan off, and told the men to go on while I waited behind till it got cooler. Late in the afternoon I set out with a light heart at the idea of quitting this most unattractive camping place. I had only gone a short distance when I found my whole caravan outspanned. It was one of those occasions when one feels so angry that words are inadequate. The men I had brought with me had evidently made some conquests in the village we had just left and were determined to spend the night there. I held a rapid inquiry and adjudged the ringleader to receive ten strokes. His comrade in wrongdoing who was ordered to administer the punishment made the position more ridiculous and me more angry (if that were possible) by proceeding to beat him as if he were a piece of Dresden china. I soon rectified this error by giving the punishment myself. I did not like the looks of the three Somalis, so before sitting down to drink some tea I took away their rifles and laid them against the table. In the middle of tea the three men came up to my table and said they wanted to speak to me. Then with a bound they rushed to the table, seized their rifles, and fled into the bush. I was never more taken by surprise in my life. I was now left with one cook and one personal servant to load all the camels. How long it took I should not like to say, but it was done at last and we continued on the road to Wajir.