Birdscapes

It would be interesting if some real authority investigated carefully the part which memory plays in painting. We look at the object with intent regard, then at the palette, and thirdly at the canvas. The canvas receives a message dispatched usually a few seconds before from the natural object. But it has come through a post office en route. It has been transmitted in code. It has been turned from light into paint. It reaches the canvas a cryptogram. Not until it has been placed in the correct relation to everything else that is on the canvas can it be deciphered, is its meaning apparent, is it translated once again from mere pigment into light. And the light this time is not of Nature but of Art.

Winston Churchill, amateur painter

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes but in having new eyes.

Marcel Proust

Birdscapes

Birds in Our

Imagination and Experience

Jeremy Mynott

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2009 by Jeremy Mynott

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton,

New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

All Rights Reserved

Mynott, Jeremy.

Birdscapes : birds in our imagination and experience / Jeremy Mynott.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13539-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Bird watching. 2. BirdsPsychological aspects. 3. Human-animal relationships. I. Title.

QL677.5.M96 2009

598dc22 2008036405

press.princeton.edu

eISBN: 978-1-400-83283-5

R0

Illustrations

Plates (between pp. 11415)

1 . (a) Swallows from the spring fresco, Thera; (b) yellow (flava) wagtails

2 . American spring warblers

3 . (a) Hoopoe; (b) roller; (c) barn owl in flight

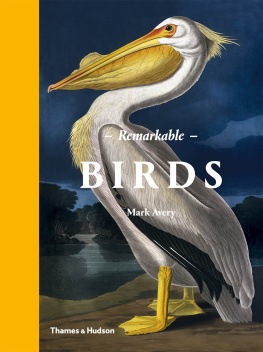

4 . Audubon paintings: (a) wild turkey; (b) golden eagle; (c) Leachs fork-tailed petrel

5 . (a) Liljefors, Golden Eagle and Hare; (b) sea eagle in flight; (c) Lear, Eagle Owl

6 . (a) Peacock; (b) the four blue macaws; (c) Australian fairy-wrens

7 . (a) World robins; (b) Christmas card robin; (c) Christmas biscuit tin

8 . (a) North American sports logos; (b) British stamps

Figures

Preface

I end at the beginning, like most authors. Just as well too. Strategic planswhether for books, businesses, wars, or livesalways look more convincing if they are written after the event rather than before it. This book, at any rate, has been in the nature of an exploration for me, a journey whose sights and sounds I did not fully foresee when I started and whose destination was unclear. I have, however, resisted the temptation to rewrite the beginning to plot the route in the full glare of hindsight, hoping thereby to involve the reader more fully in my own ruminations, surprises, and discoveries along the way. The journeys the thing, and the conclusions, such as they are, dont make any sense without it.

There is, however, a deliberate structure it may be useful to mention briefly. The first two chapters start to define the questions to be explored in the later, more substantive ones, which are on such things as rarity value, the physical qualities of birds, sound and song, landscape and season, bird names and symbols. These initial questions are developed, and I hope enriched, by the many examples and experiences (mine and other peoples) that I examine in the course of the enquiry, and the chapters tend to get longer and more detailed as the book goes on. Each chapter starts with a diary note of an actual encounter, and I try to use these anecdotes to show how the topics that chapter deals with can arise out of such experiences. The chapter then goes on to offer some analysis and muse on the results. I make a lot of use of quotation, some of it unconventional for a book about birds, both to vary the voices and to enlarge the frame of reference. There are notes of two kinds: footnotes (mainly for self-interruptions, titbits, and asides) and endnotes in the reference section (mainly for bibliographical sources and references). There are also four appendices for larger digressions. Certain themes recur throughout the bookthe snares of sentimentality, the pros and cons of anthropomorphism, the interplay between what we perceive in birds and what we project onto them, and the power of metaphors, names, and symbols to express or distort our vision. But that is already to make sound abstract and remote what is best understood through particular live examples, which is what I try to offer. Each chapter is self-contained, but there is a sort of spiral progression through these ideas, with many wanderings and wonderings, like revisiting a landscape (or indeed a bird) from different directions and at different times and seasons to gain a fuller picture. This is not a systematic treatise of any kind, rather a series of linked reflections. The mode is conversational, the mood enquiring and sometimes playful.

I wrote this book quite quickly, in exactly a year after signing a contract for it. I realised while doing so, however, that I had really been contemplating it for quite some time. It has been a way of making conscious the reasons that have sustained my interest in birds over so many years. I have many people to thank for their company in doing this. First, my brother, Simon, who got me into all this and in particular taught me birdsong at a very early agethe best present he ever gave me. Then other friends and familymy nephews Philip and Graham, my longtime companions Malcolm Gibbons and David Jennerwho have all loyally accompanied me on trips to remote places where our objectives must have sometimes seemed puzzling to them. After all, why would one sit on a cliff in an uninhabited island beyond the Outer Hebrides, at two in the morning in the rain, and declare oneself so happy to have heard (though not really to have seen) some small dark petrels flying in off the sea? Philip Allin also has made many memorable trips with me in Europe, and Steve Edwards has for many years been a most agreeable and knowledgeable companion for the Scilly season. I have enjoyed many relevant conversations with each of them, during both the birding and the aprs-birding, and both have read and commented in detail on my draft chapters. Tony Wilson has yet again amazed me with the acuity of his reading and has saved me from many errors, not for the first time in my career. Sarah Elliott has been a perceptive and entertaining guide over the years to all the inhabitants of Central Park, New York, and I have learned a lot from her about both birds and birders. Marek Borkowski shared both expertise and ideas with me on a memorable trip many years ago to the Polish marshes and forests, which I now realise got me thinking about some of these topics. Other experts have read parts of the text and made many detailed suggestions, as well as giving me important encouragement: Mark Cocker and Jonathan Elphick (several chapters), John Fanshawe (). Princeton University Presss two readers, Stephen Moss and Wally Goldfrank, have been a wonderful source of advice throughout the project: each has read the whole thing in draft and made many excellent suggestions, with Wally giving invaluable guidance on the North American and neotropical examples in particular. Caroline Dawnay and Ivon Asquith were also important advisors at the early stages, and Caroline has stayed loyally with the project and been a great friend to me and the book despite disruptions to her own professional life.