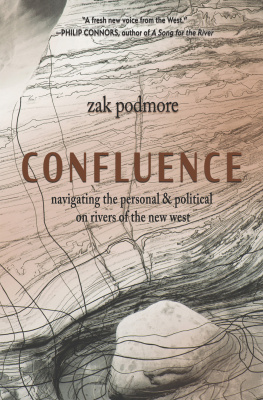

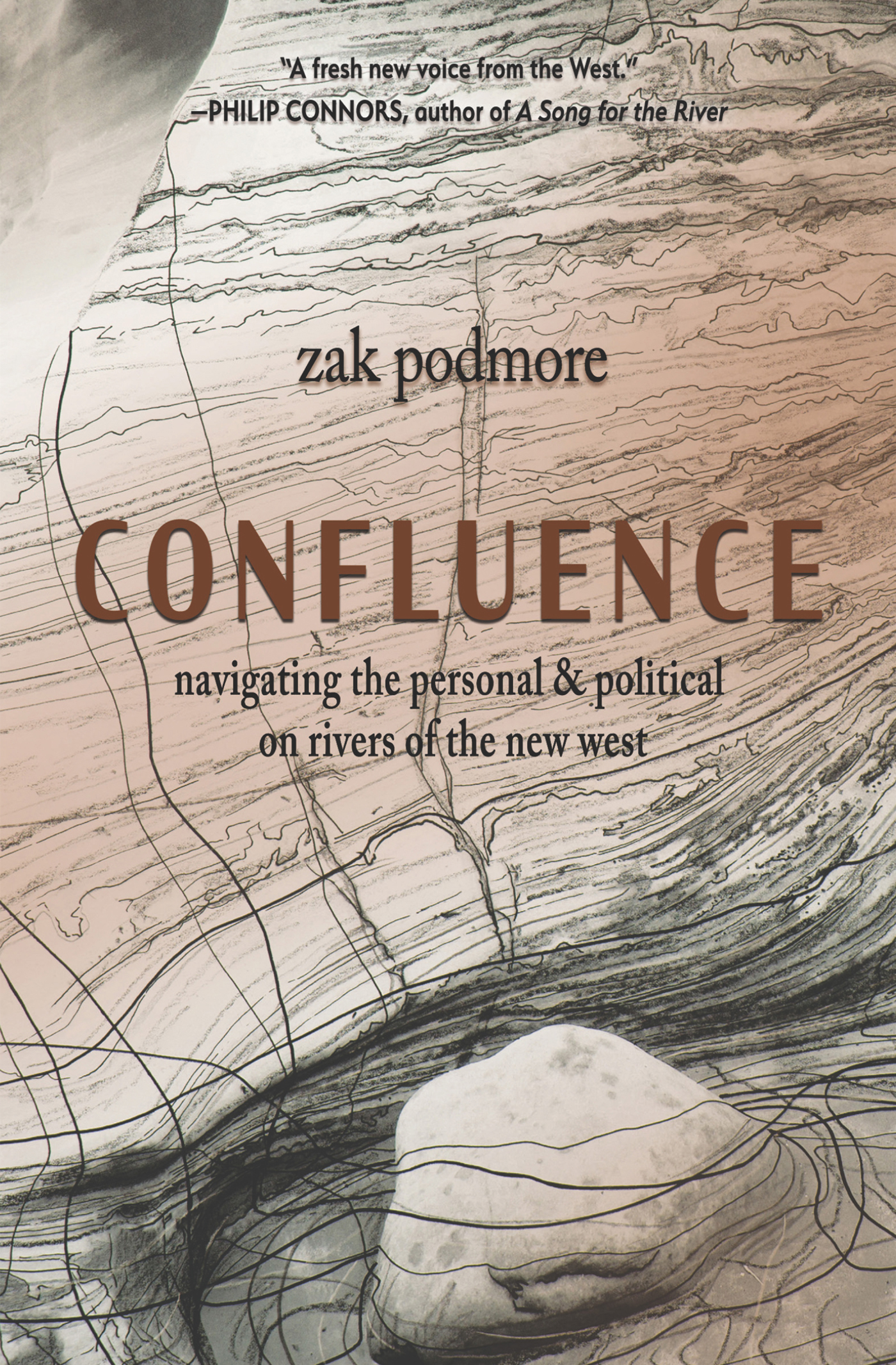

CONFLUENCE

CONFLUENCE

navigating the personal & political

on rivers of the new west

zak podmore

TORREY HOUSE PRESS

SALT LAKE CITY TORREY

First Torrey House Press Edition, October 2019

Copyright 2019 by Zak Podmore

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or retransmitted in any form or by any means without the written consent of the publisher.

Published by Torrey House Press

Salt Lake City, Utah

www.torreyhouse.org

International Standard Book Number: 978-1-948814-08-9

E-book ISBN: 978-1-948814-09-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932477

Cover art White Canyon by Julia Klema

Cover design by Kathleen Metcalf

Interior design by Rachel Davis

Distributed to the trade by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

For Ruth,

the mother who raised me in desert canyons

CONTENTS

Wherever the river flows, it will bring life.

Ezekiel 47:9

I ts early summer and the water is high. My mother grasps the handles of two wooden oars and feels the Colorado River surge through her arms. A gray ring of raft surrounds her, sixteen feet from bow to stern, and beyond it, the mud-red river roils. Near the bow, her friend and former college roommate sits on a cooler. Theyre raft guides out for a week in Utah canyons with no clients, and theyre nearing the crux of the trip: a feature known to river runners, in both fondness and fear, as Satans Gut. Directly downstream the Gut heaves in a gnashing pit of foam large enough to swallow a Winnebago. River and air are locked in combat. The water billows up in angry clouds that never manage to sail into the sky but are pulled under again and again. Other boats in their party have already disappeared beyond the maelstrom.

As the current gathers speed, the world tilts. The first waves at the top of the rapid crash over the gray tubes and the raft fills like a bathtub. That morning the boats load of army-surplus ammo canspacked with apples, peanut butter, and beerwere lashed to the metal frame under a net of faded webbing. Now they float beneath their restraints. The woman in the front of the raft stands knee-deep on the floor and bails with a five-gallon bucket twice before sitting back down and grabbing onto a strap.

Bracing her feet against a box, my mother pulls back on the Douglas fir oars so they bend against the water. Deep in the woodgrains, fibers creak and snap. But the rafts course cant bealtered. The front tubes cross the upstream edge of the hole and the boat tips smoothly into its mashing heart. A white wall of water rolls across the bow and smacks my mother square in her lifejacket. The boat, more ballast than flotation, barely slows as the oars are ripped from her hands.

The raft continues downstream. My mother does not.

She circles in the hole three times like a paper bag blowing through a culvert. As if compelled, she folds her knees to her chest and lets a deeper current pull her far below the roar. Ears pop as knees graze the limestone cobbles imbricated along the river bottom. All at once, it is quiet, dark, calmeven peaceful. She tumbles and does not know which way is up. Her lifejacket doesnt seem to, either.

She was twenty-five then, my sister and I still dreaming in the void of uncreation. When shed tell the story to me later, shed always gloss over her time underwater, but I could tell by her face that lifetimes were contained in the minute or two she spent beneath the Colorado River, that severed umbilical cord which once ran from the Rockies through the desert to the sea. I do not know what thoughts moved through her mind while she was submerged. I do not know what messages were pressed to her eardrums, what visions played through the pressure on her eyelids. But Im aware that such moments are rarely silent; there is an abyss between the surface realm of the rower and the underworld of the swimmer. Over a life of river running, Ive crossed that gap more than once. Time begins to stretch and bend below the surface. Unheard voices start to speak, even if their words cannot be repeated after breaking back through to the sanity of the day. As my mother sank all those years ago, I wonder what lights shone in the galaxies of her memories. Or was it all darknessa wash of panic? Its too late to ask her now.

She did tell me the storys conclusion, though. Just as her searing lungs felt they could take no more, the river released its grip. The current slackened into a calm pool beyond the rapid, and thefoam flotation around her chest began to propel her upward as if it were attached to the sky by a string. Her head broke through and dry air screamed into her lungs. Rescue ropes came slinging across the water from the half-circle of rafts around her.

There she was, located again, neck-deep in a river that carves through the bottom of the Colorado Plateau. The sun blazed on the broken stone blocks that spilled down from the canyon walls. The sediments in the river swirled like high country emissaries from the Never Summer Range, the Uintas, Abajos, La Sals, Wind Rivers, and San Juans. All around, dry washes tipped steeply toward the Colorado as if the arid landscape were bowing to the river, to the surging rapid, and to my mother, alive.

HOME SOMETIME TOMORROW

Spring 2017

T he world moves past at two miles per hour. Outside the van window, clusters of gray-green sagebrush fidget on roadside dunes as wind whistles through the door gaskets. My pen scratches across a notebook page while Ute Mountain Ute councilwoman Prisllena Rabbit speaks to me about her homeland, the traditional hunting grounds of her relatives not far from the road.

When the grandmotherswhen Thelmatells me I need to be somewhere, I listen, she says. Her hands are folded on her lap. An ink-drawn bear snarls from her T-shirt underneath the words White Mesa Says NO to Uranium. Prisllena is serving her second term on the tribal council in another reservation town, but Thelma, who is two rows ahead of us in the fifteen-passenger van, lives nearby. Shes a respected matriarch in the three-hundred-person village of White Mesa. Her short black hair and large turquoise earrings are visible above the seatback. Through the windshield, tufts of grass, already yellow in late spring, lay down in the gusts of wind.

The van creeps along at an idle, matching the pace of the ninety protesters spooled out before us on the highway shoulder. I dont need to ask any questions. Prisllena keeps on talking and she is not someone you interrupt. The Creator made us a unique kind of being, she tells me. Look at how long our lifespan is compared to other animals. That gift allows us to step onto the land and respect itand then leave it alone. We need natural elements to survivewood for cooking and medicine from plants. But we borrow with respect for our neighbors, the bear and other animals, and the water. How does a humanhow does anythingsurvive without water?

Next page