I stumble wildly through life and am only kept from falling on my face by the caring people who catch me and right me. I have a lot of people to thank.

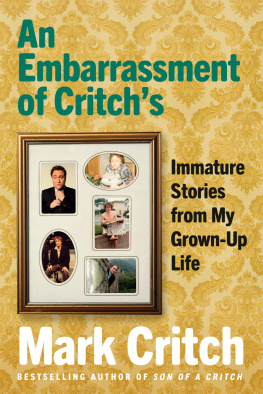

At Penguin Random House Canada, I would be lost without the leadership of Nicole Winstanley and Scott Sellers. Thanks to Beth Cockeram for her marketing genius and to my incredible publicist Dan French. Leah Springate and Terri Nimmo provided the lovely design and the cover that you probably judged this book by. And a huge thanks to my editor, Laura Dosky, for her guidance, patience and gentle nudging.

Thanks to my former literary agent, Madeline Wilson, for getting me to sea and my current agent, Michael Levine, and the team at Westwood Creative Artists for seeing me safely to shore.

I have to thank my sons, Jacob and Will, for their constant support and for making my heart burst with pride. Thank you to my brother Mike for always having my back and my soul brother Tristy Clark for being the best friend I could ever hope for.

Thank you to my wife, Melissa, for being the smartest person I know. I am delighted to be the worst decision you ever made. And to Cathie, Dave, Mike, Jess and Pop, thanks for dinner conversation that is much cheaper than therapy.

And to Donna Butt and the people of Trinity, thanks for giving me my start and for taking a prodigal son back home.

1

LEAVING HOME

What do you want to do when you grow up? my father asked me. I was taken aback. I was seventeen at the time. I thought I was a grown-up. I was too young to know I wasnt an adultold enough not to know better, but young enough not to know a damn thing. Ignorance is bliss and I was the happiest man on earth.

My father, on the other hand, was seventy-six. He was a retiree with a high school graduate on his hands. I was what my Catholic family would call a blessing but what most people would acknowledge as an accident, or at the very least the result of one too many beers at the office Christmas party. I was the hangover that just wouldnt go away.

I suppose Dad looked at my graduation day the way a warden might look at his last remaining prisoners parole date. A certain amount of freedom was on the horizon for both parties involved. You could get a trade, he suggested. We both knew that wasnt an option. I was a thin, asthmatic epileptic with weak ankles. I couldnt see myself taking a welding course any time soon. This conversation had been coming and we had both avoided it like a married couple pretending they hadnt already been divorced for years. The admission was simply a formality.

I want to be an actor, I said, aging my already grey-haired father another decade he couldnt afford to lose. Dad avoided my hopeful gaze. He looked down at his brown leather dress shoes. They were scuffed from years of work and worn into something comfortable yet still formal, much like he was.

I could get you a job researching deeds, he said, deflecting my truth like Wonder Woman blocking a bullet with her metal bracelets. My father came from a time when you took a job because you could get one, not because you chose it. His father had died of tuberculosis when my father was just five years old. His mother went in service, scrubbing the floors of wealthy St. Johns families while my dad roamed Water Street for odd jobs to help keep a roof over their heads. He would remind me that he had fought tooth and nail to crawl out of the grip of poverty. Now, I was trying to shake its hand.

Hed known this day was coming, though. There had been plenty of warning signs. I had been in school plays. Id formed a sketch comedy troupe. I spent every free moment writing. My room was filled with scripts and costumes. There was no escaping it. His son was an artist. I want to be an actor, I argued. Its who I am.

But you could still be yourself on the side, couldnt you? he countered. Good god. This is not the time to be clowning around with that foolishness. The arse is out of er.

The only job my father had left in life was to get me on a steady path, and his method was somewhere between a bird gently nudging its hatchling out of the nest and a man tossing a bag of garbage onto the curb without looking to see where it may fall. But he had a point. I was entering the job market just as thirty-five thousand other Newfoundlanders were put out of work overnight.

When John Cabot first discovered my homeland of Newfoundland in 1497 (much to the surprise of the native Beothuks who lived there), he wrote that you merely had to place a basket over the side of the ship and when you pulled it back up again it would be teeming with cod. You didnt even need a net.

By the time I graduated from high school in 1992, though, you couldnt find a cod if you drained the ocean. Decades of overfishing had depleted the cod stocks. In a desperate move, the federal minister of fisheries and oceans, John Crosbie, a Newfoundlander himself, shut down the northern cod fishery after five hundred years, ending the greatest fishery in the world with the swipe of a pen.

Crosbie was labelled a traitor. When a group of angry fishermen surrounded him on a wharf, he stood tall and told them that he didnt take the fish out of the goddamn water. If it hadnt been true, they might have killed him. The moratorium was meant to give the species time to rebuild but they still havent come back. Maybe, like many other Newfoundlanders, the cod had simply moved to Alberta to work in the oil sands. Nobody knows.

I had wanted to become an actor in a part of Canada where, months earlier, it was much more realistic to become a fisherman. But in 1992 that situation changed, and my chances of making it as a comedian were suddenly just as feasible as a life at sea. There was no future in either.

None of the sudden economic disaster affected my family, though. My father was a newsman. He worked in AM radio, and bad news was good news for the Critches. I grew up right next door to his radio station in the capital city of St. Johns. My bedroom view was of satellite dishes and radio towers, not waves and lighthouses.

I didnt know any fishermen. I hadnt even been outside of the city in my life. The Critches were not nomadic people. I would watch in wide-eyed wonder as the richest kids in my class showed me the pictures of their family vacations. Florida! New York! Moncton! Our family never went anywhere. We only took one trip a year and it was not to Disneyland or MarineLand. It was to Newfoundland.

We would pack our bags and take the bus to the park that lay eight kilometres away. The old man acted as if that eleven-minute drive was akin to Lindberghs hop across the Atlantic. A lunch was packed, watches were synchronized, and the night before was a restless one.

Mary, my father would shout to my mother, having shot upright in his bed, do you have the bus schedule? Whens the last bus? Good god! We dont want to miss that! Well be stranded. Well have to sleep on the street.

Nobody enjoyed the trip to the park more than my father, and he hated it. Dad never changed out of his suit. He would watch me splashing in the pool like he was paying by the water drop. Isnt that long enough? he would ask, staring at his watch. Youre plenty wet now. He wouldnt calm down until we were sitting on the bench at the bus stop, a full three hours early. Id stare out the window on the ride home, dripping onto the faded vinyl seat. I was fascinated by the strange neighbourhoods that whizzed past me. I wished that I could spend some time exploring that world. I wanted that almost as much as I wished I had been allowed to change out of my wet trunks before we boarded the bus.