Albany, NY. 12203

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the author.

Excerpt from White Apples from White Apples and the Taste of Stone: Selected Poems, 1946-2006 by Donald Hall. Copyright 2006 by Donald Hall. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

This book is not intended as a substitute for the medical advice of physicians. The reader should regularly consult a physician in matters relating to his/her health and particularly with respect to any symptoms that may require diagnosis or medical attention.

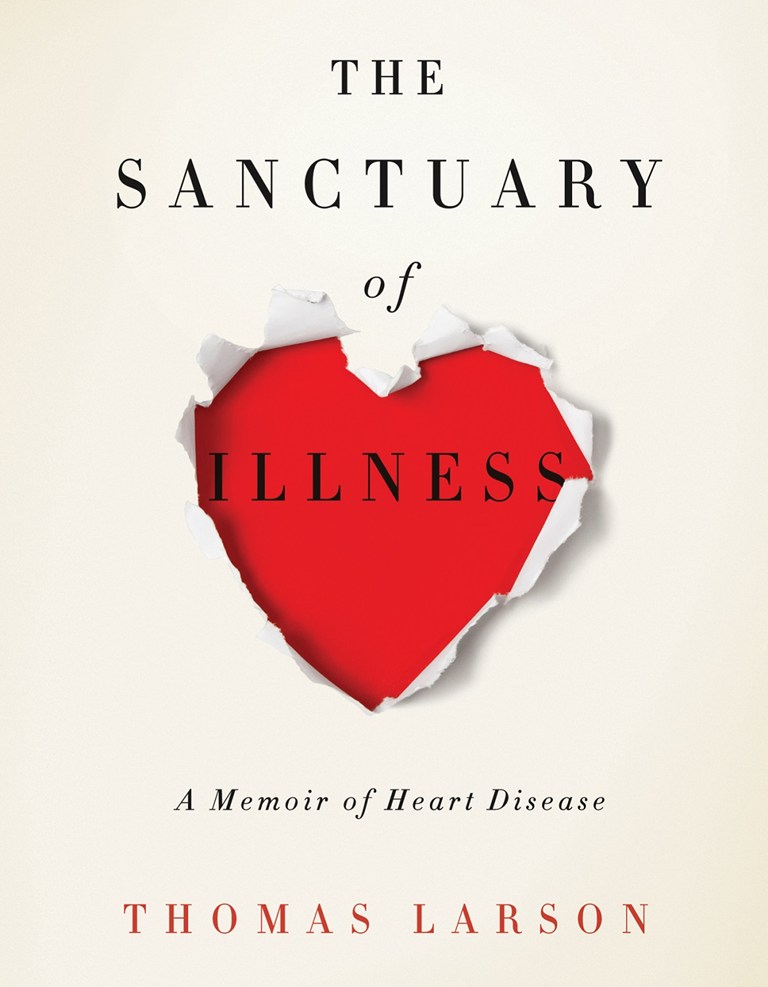

Cover design by Philip E. Pascuzzo

To my father, who died of heart disease at sixty-one.

To my older brother, Steve, who died of the same at forty-two.

To my younger brother, Jeff, who, fearing cardiovascular illness, lost seventy-five pounds before his sixtieth birthday.

As long as humans feel threatened and helpless, they will seek the sanctuary that illness provides.

Dr. Robert R. Rynearson

ONE

... this monster, the body, this miracle, its pain...

Virginia Woolf, On Being Ill

Christ, Not Now Its March, Im at home in San Diego and getting ready to teach my Monday evening class. Its strange: in the hour prior, Im hot, sweaty. Constipated. Confused. Breathless, having just lumbered up the stairs to Suzannas and my bedroom. The second storyhow many times have I done that? I tell myself its work, its stress, nothing else. Im out of shape, easily winded. Indeed, for months, Ive been trudging on the treadmill, a lot slower than usual. But Im not sick. Im older. What age? I have to remember. Fifty-six. Driving to class, Im heating up, rolling down the window for a breeze. At class, Im no better. I give my flock a writing assignment, which I check, moving from student to student. Ten minutes pass this way. Then I excuse myselfa quick bathroom stint, I think, should dispel this acidic burn in my throat. I lean into the toilet, try to vomit. Nothing. I crap, blow-it-out like bird shit. Thats got it. I rush back to class, wondering whats happening? I dont know. I do know I dont want to suffer in the way Im suffering right now. How will I make it through the next three hours? Ive never left in the middle of a class, and only twice in fifteen years have I canceledthe day my mother died and the day one of my twin sons left home, leaving a cryptic note that terrified Suzanna and me. I rationalize ittonights lesson needs completing. Its amateurish to postpone the work. Maybe I can do ten minutes on each essay weve read and let them go. From my notes, I outline on the board the writing strategies in each piece. And here it gets strange. The taste of reflux soils my mouth. I feel as though Ive just plunged off a cliff and halted midair. Afloat, I sense there is no future: however many years are telescoped into these few minutes. Years into minutes . A spiral appears, widens, pinwheels, and sucks me in. I recall how Ive told students its a copout to say, It felt like an eternity or Time dragged on or Hours rushed by. Clichs, Ive called them. How do you capture trauma, intensity, in words? Theres no other side to this thought. I discuss one essay in two minutes, the next in a minute, the next, in thirty seconds. My words are boggy, slow. Then I hear myself speakas though Ive been called onIm afraid Im not feeling well. I have to leave. In my bag, I stuff books and papers. My hands sweat. My legs quake. For next week, I sayand stop. Everyone is looking at me. I have to leave. Im running.

Clothes Off A nurse takes me to an emergency room bay. Symptoms? she asks. I think Im having a heart attack, I say again. She tells me to get undressed. Im sitting on the bed, and begin taking my clothes off peeling , thats the word. Theyve been stuck on me like a soiled diaper for half an hour. My body is leaking its insides. Its not the soul coming out, wet and furious. Its my skin, like packaging, trying to strip itself of the invader. These goddamn clothes nag because they curtain my fat, a lifelong source of shame. For several years Ive gained weight (again)in the 1980s, a runner, I was svelte; in the 1990s, I got so sedentary and lazy teaching full-time I put the pounds back on; now, in the 2000s, a full-time writer/journalist, and I procrastinate getting back in shape, my belly jellying, a midlife bulge pushing me to 220. I hate the weight. I hate unbuttoning the faded pink travel shirt Ive worn for years. I hate unclasping the stretchy waistband pants, size 40, all this so pungent, so whinyI dont want to see the tumescence over my too-tight underwear: how often I hide behind a T-shirt prior to sex with Suzanna (What sex? Its been months). Why dont I stop worrying? Stay here, the nurse says, Im coming right back. As if Im going anywhere.

Where is the drug to curb/redirect this avalanche?

Where are my saviors?

I put on the gown. To hell with the ties. I get back on the long plastic mat.

An orderly enters, wires me up to the ECG machine, prints out a graph-paper page on which I espy its Himalayan-like peaks and valleys. He hustles out. He returns. With a well-groomed pro, the Doc, in crisply tailored whites, who tells me what Ive known now for an hour: Youre right, Mr. Larson. Youre having a heart attack.

Im Sorry Is it then that the nurse asks the mandatory questionsmy name, my address, my date of birth, my cardiac history (do I say, father, brother, both dead: of heart attacks , or the less volatile, heart disease ), my symptoms (Im dizzy, Im hot, my chest aches): Have you ever had angina before, a sudden name for the pain that keeps washing through me? Does she lean over next and smirk a tad wickedly and say, Please try and relax, and I laugh? Does it happen a minute later that she rifles a medical bag for aspirin and a sublingual nitroglycerin tablet, and asks, almost like an afterthought, who to phone, and I say, Suzanna ? While I wait, harried and calmed by the theatrical flurry, the pinging machines, the seismic readouts, you appear, curtain-parting and padding your way up to the bed where I lie and where on your face I see two women, you who are unafraid to approach me, indeed, desire my trouble, and you who are shocked to come any closer

To both of you I say, Im sorry.

Dont be, you reply.

But I am.

What for?

Good question.

Im sorry that this dread wants you , as well as me, to bear it.

Dont Drive Yourself But I did. My last act of volition. Isnt that why Im alive and being helped? I got here lickety-split. For which I think I should receive some credit. Ah, were dialoguing. Im out of danger. Indeed, Im purring and holding onto Suzanna, who smiles at the busy, fraught nurseSuzanna, a psychotherapist, whom Ive been with for seventeen years (our home offices adjoin), who is beside me, which means I will make it. I love her for magically appearing: our eyes (hers, herb-garden hazel; mine, sky blue) lock and promise well work the shock outand what it means for uslater. She and the nurse are iterating how right it was I came in. Though I could have called an ambulance, you know. But I was just a mile away, I say. I dont mention that I knew where the emergency room was because six weeks earlier I had rushed to this hospital, Scripps Green, a half mile from the beach at La Jolla, when I was half-panicked, a chunk of silicone that I had buried in my ear canal for silence while sleeping was stuck. Id had underwater hearing and couldnt think straight. The shock of the $350 bill came later, but the good doc tweezered the greasy lump out, then told me never to do such a dumb thing again. I also dont say that an hour earlier while hustling to my car I thought to drive home, a jet-fast three miles to get Suzanna and, with her, figure out what was wrong. This nurse would have admonished, Had you done that, you probably wouldnt be alive.