Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lehto, Steve.

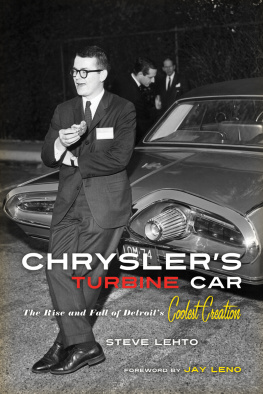

Chryslers turbine car : the rise and fall of Detroits coolest creation / Steve Lehto.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-56976-549-4

1. Chrysler automobileHistory20th century. 2. Experimental automobilesHistory20th century. 3. Automobiles, Gas-turbineHistory20th century. I. Title.

TL215.C55L47 2010

629.222dc22

2010023636

Interior design: Sarah Olson

2010 by Steve Lehto

Foreword 2010 by Jay Leno

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-56976-549-4

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Jennifer,

and my brothers:

Ken, Bruce, Dave, Rick, and Tim

Contents

Foreword BY JAY LENO

In 1964, when I was fourteen years old, my family visited the Worlds Fair in New York. I wasnt old enough to drive yet, but I already loved cars, and I had heard about two that were going to be on display there. One was the new Ford Mustang, which, quite frankly, was the worst-kept secret in Detroitthere were plenty of pictures of that around. The second was the Chrysler Turbine Car, which was far more interesting. It had a totally new and different powerplant that had never been put in an automobile before: a jet engine. To be honest, I dont remember all that much about the Mustang from the Worlds Fair. But I remember everything about the Chrysler Turbine Car.

Chrysler had a huge display at the Fair, and the centerpiece was a small track where they were giving rides in the car. The lines to ride in the car were long, so I simply walked over to the edge of the area and looked at the car. Everything about the car was memorable. It had the lines of a space age carnot like the silly fins of cars from the 1950sand even its turbine-bronze paint was unique. When the car started up and drove around the track, the sound it made was unlike anything Id ever heard before. I watched it and was in awe. Would they be building and selling these cars by the time I got my drivers license? I hoped so.

Every magazine from Popular Mechanics to Hot Rod had articles about this car. Will the Piston Engine Be Obsolete in Ten Years? Is This the Automobile of the Future? At a time when the rest of the world was just getting piston-engine cars, America was moving on to jet-powered automobiles! Then, suddenly, the whole thing disappeared. Within a brief span of two or three years, all talk of turbine cars was gone. What happened? Where did they go? As the years passed, I learned that most had been destroyed by Chrysler. Why?

I finally achieved my dream of owning one of these cars in 2009. I found it to be a practical, quiet, and nice running automobile that could run on a number of different fuels. Tequila, diesel, perfumeanything that would burn with oxygen could fuel this car. What happened to this amazing automobile? In this book, Steve Lehto gives the most detailed and in-depth analysis of the engineers behind this program and their amazing auto. Here is the story of what happened to their dream of building a gas-turbine car.

Introduction

On a blustery December day in 1953, George Huebner Jr. and his fellow engineers at Chrysler rolled a top-secret car out of a garage in Highland Park, Michigan. No one outside Chrysler knew the car existed. In fact, it was hardly known within Chrysler. The 1954 Plymouth Belvedere didnt appear special until it was started. First a high-pitched whine, then a whooshing roar, split the cold air. It sounded like a jet. Powered by a jet turbine engine, the car roared without vibration.

Over the next two decades, Huebner and his engineers from the Chrysler Turbine Lab would build more than seventy jet cars, including a fleet of fifty that would be lent to the public in an unprecedented publicity campaign. The plan worked to perfection as the cars logged over a million trouble-free miles on five different continents.

The turbine engines required some unusual manufacturing processes, but the team hoped those issues, which would be quite expensive to resolve, could be addressed after they had proved the viability of the turbine cars. The cars also offered a solution to a problem that even Huebner and his colleagues could not have foreseen: the cars ran on any flammable liquid. Not just gasoline but diesel, kerosene, jet fuel, peanut oil, alcohol, tequila, perfume, and many other substances fueled Huebners turbine cars at one time or another. Because this was pre-OPECand no one could have guessed that gasoline would ever cost more than a fraction of a dollar a gallonthe cars ability to burn a wide range of fuels was largely overlooked.

How different would America be now if we all drove turbine-powered cars? It could have happened. But government interference, shortsighted regulators, and indifferent corporate leaders each played a role in the demise of a program that could have lessened U.S. dependence on Middle East oil.

The Promise of the Jet Age

In the decades following World War II, the jet engine symbolized new technology that would propel the average American into the life of the future. After all, the cartoon stone age family was the Flintstones; the space age family was the Jetsons. Cars wore jetlike tailfins and other design touches to make them look as if they were designed by NASA and might wander off the planet one day. In 1962, John F. Kennedy announced to the world that America would lead the space race by sending a man to the moon and back. Science and technology were making promises that attracted attention and sparked imaginations. Soon, it seemed, we could all travel by rockets and jets.

The jet turbine, in its most basic form, is a relatively simple concept. Imagine a tube with a fan at the frontthe compressor rotorand a fan at the backthe turbine rotor. Run a shaft through them both, spray fuel between the rotors, inside the tube, and ignite it. When the air and fuel ignite, the combustion gives off hot gases, which expand and force their way past the turbine rotor. This causes the shaft connecting the rotors to turn, spinning the compressor at the front end of the tube. The compressor rotor will draw in fresh air and, as the blades gain speed, push more air into the combustion chamber. As more air gets forced into the chamber, the reaction becomes increasingly stronger; the rotors reach amazing speeds if everything is set up right. The exhaust from this contraption can put out enough thrust to push something as large as an airplane. Direct the exhaust at another set of fan blades that turn a gear set and the turbine can run a variety of devices: boats, trains, generatorseven automobiles.

The jet turbine developed rapidly during World War II, largely driven by British and German research. Each country claimed an inventor with a patent on a jet turbine engine. Britains Frank Whittle patented his design in 1930, while Germanys Hans von Ohain registered his with the German patent office in 1936. Both countries rushed to develop a turbine engine that could create enough thrust to power an airplane just as they went to war against each other. The later patent date of the German engine didnt reflect who flew first; the Luftwaffe put a jet aircraft into flight in 1939 and was using operational fighter jets in 1943. The British got theirs off the ground a couple of years after the Germans, and the jet race was on. Soon, inspired by the successes of the British and Germans, engineers around the globe were developing turbine technology.

Next page