The Author

Peter Townsend was born in Rangoon, Burma in 1914. He trained at the Royal Air Force College Cranwell from 1933 to 1935. He served with No 1 and No 43 Squadron and in May 1940 took command of No 85 Squadron leading it into the Battle of Britain with outstanding skill and determination. Townsend enjoyed an equally distinguished peacetime career, serving as Equerry to King George VI, from 1944 until his death in 1952. Following his ill-fated relationship with Princess Margaret, Townsend began a new life in France where he turned to writing and settled happily with his family until 1995 when he died at the age of 80.

DUEL OF EAGLES

Peter Townsend

SILVERTAIL BOOKS London

Dedication

For Marie-Luce

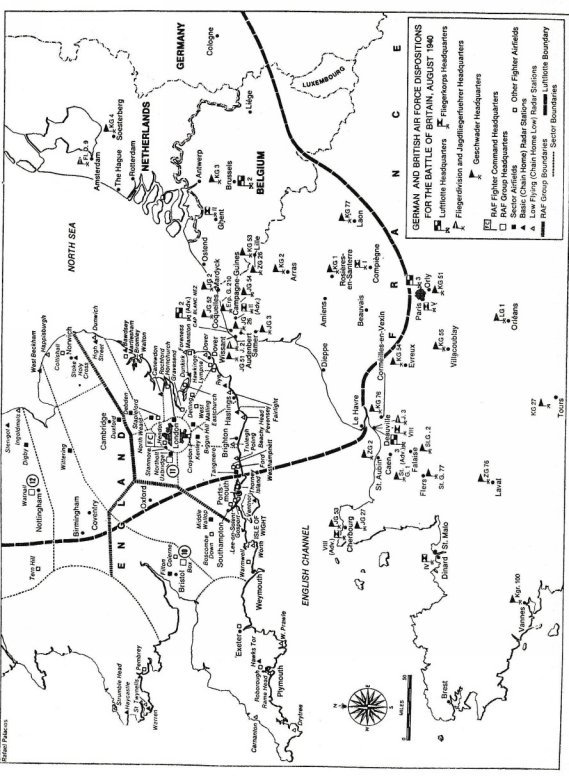

MAP OF GERMAN AND BRITISH DISPOSITIONS FOR THE BATTLE OF BRITAIN, AUGUST 1940

Prologue

3 February 1940

Standby, standby, standby... The steady voice of the girl duty operator at Danby Beacon Radar Station on the Yorkshire coast, was heard two hundred miles away by another girl at Fighter Command Headquarters.

At that moment, 9.03 a.m. on 3 February 1940, Heinkel 111 No. 3232 of the Lion Kampfgeschwader was approaching the English coast. Hostile 2 now at thirty-five miles, Charlie 2710. Height one thousand, said the quiet voice from Danby Beacon. Fighter Command flashed the information to 13 Group Headquarters at Newcastle.

A few miles up the coast, at Royal Air Force Acklington, the telephone rang in 43 Squadron Pilots room. Blue section scramble, and a few minutes later three Hurricane fighters rose into the chilly morning air.

I was in the lead, Folkes and Hallowes following close in my wake. Vector 180, Bandit off Whitby, Angels one. We raced south at full throttle, a few feet above the waves, to have the best chance of seeing the enemy first.

Achtung, Jger ! Suddenly Peter Leushake, the Heinkels observer, saw three fighters curving up steeply from below. The words were hardly past his lips when bullets ripped into the Heinkel and killed him. At the same instant, in the lower gun position, Johann Meyer, the flight engineer, was badly wounded. Only Unteroffizier Karl Missy, in the top rear gun position, remained to defend the stricken aircraft. He aimed carefully and fired at the leading Hurricane. His single MG15 machine-gun was a feeble answer to the eight .303 Brownings of the British fighter, which was firing again. Missy never moved from his swivel seat at the gun position. He knew the fighters second volley had hit him, but how badly he could not tell.

Hermann Wilms, the pilot, pulled the Heinkel up into the cloudlayer just above, but the speed dropped off sharply until the bomber sagged in his hands and he knew the engines were hit. It was a mile or two to the coast, but somehow Wilms made it, gliding low over Whitby Town.

At that moment the Castle Park bus had just stopped on the Parade, and a woman who got off had the fright of her life when she saw the Heinkel loom just overhead, so low that she caught sight of Wilms through the cabin window and the black swastika on the Heinkels tail. To her and to hundreds who were now watching with her the swastika meant one thing only: a Nazi. This was one of Hitlers bombers and it had brought the war to Whitby.

Unteroffizier Missy was in a serious condition when I visited him in Whitby hospital next day. I brought him a tin of Players cigarettes, small compensation for what I had done to him and his comrades. I was sorry for him, not for my actions. Afterwards I often thought of the mute, pathetic look he gave me and the way he clasped my hand, but never that I should see him again.

Twenty-eight years later in Rheydt, Missy opened the door for me of the home where he was born and where he now lives. In the hours that followed he told me how he came to join the Luftwaffe and to be in Heinkel 3232 that day.

We and a few hundred others on both the German and British sides were of the second generation of airmen, born when the aeroplane, too, was in its infancy. My story tells how some of us came to fight each other to the death over England in the summer of 1940.

Missys Heinkel made the news next day. It was the first enemy plane to crash on English soil in this war, the RAFs previous success having been in Scotland, announced the Whitby Gazette with a nice touch of north-country pride.

On 3 February 1940 a tall, straight man with a voice of thunder was celebrating his birthday. In his own service and no one more than he could call it his own, for he had built it everybody called him Boom. Marshal of the RAF, Lord Trenchard, was sixty-seven that day. It was a trivial, but perhaps not entirely irrelevant coincidence.

Part One

THE FLEDGLING YEARS

Chapter 1

On 18 May 1918, General Trenchard had arrived at Nancy, France, to take command of a small fleet of bombers about one hundred in all. His mission was to pay back in kind the bombs which the Germans had been raining down on England during the last three years. The very next night forty-three Gotha bombers of the Imperial German Air Service set out for London. Six crashed, one in Kent at Harrietsham. Although the British did not know it at the time, that Gotha was to be the last German plane to crash on English soil until Missys Heinkel slid to a standstill outside Bannial Flat Farm on 3 February 1940...

Kaiser William himself had given the green light for the German air offensive against England in January 1915. He had strong popular support. Full of enthusiasm for the graceful, gigantic Zeppelin airships, the German people and press were at one with the German High Command in believing that the Zeppelins would break the will of the English: they had visions of London in flames. Under cover of darkness, these giant dirigible airships roamed at will, scattering their bombs over south-east England and the fringes of London. At first they caused negligible damage and killed relatively few people, but they were a nuisance, and the public indignation they provoked made the British government uneasy. Then on the night of 8 September 1915, Kapitnleutnant Heinrich Mathy, the commander of naval Zeppelin L13, cruised majestically and unimpeded over London to drop half a ton of bombs into its heart. The toll in property and lives was heavy. That night Germany took the first significant step towards a new kind of warfare: strategic bombing. The objective of Mathys mission was of course ostensibly military: but as most targets were situated in residential areas, defenceless citizens of all ages and both sexes were bound to be killed.

Strategic bombing or, more realistically, total air warfare, is a German invention, though in their turn the English later directed it against Germany. Both sides soon realized that if indiscriminate slaughter of civilians from the air had a desirable effect on the enemys morale then civilians were as natural a strategic target as munitions factories. If civilian morale was the easiest target to hit, it was also the hardest to destroy. The sole redeeming feature of this barbarous new form of warfare was to be that it fired the courage of ordinary people.

Trenchard had been appointed General Officer Commanding the Royal Flying Corps (the British Army air service) on 19 August 1915. The new C-in-C had the stature, the heart, and the voice of a giant. His aide-de-camp, Maurice Baring, wrote of him at this time that he was tall, straight as a ramrod, covering the ground quickly with huge strides and forcing his shorter aide to move in a quaint kind of turkey-trot at his side, trying to keep up with him.

Next page