Previous works by Tim Gallagher

Falcon Fever: A Falconer in the Twenty-first Century

The Grail Bird: Hot on the Trail of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker

Parts Unknown: A Naturalists Journey in Search of Birds and Wild Places

Wild Bird Photography

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

PART I

TREASURES AND TRAGEDIES OF THE SIERRA MADRE

PART II

THE FINAL EXPEDITIONS

FOR MY SON,

JACK OBANNON GALLAGHER

19942012

NOTE TO READERS:

Names of some of the people portrayed in this book have been changed.

The beauty and genius of a work of art may be reconceived, though its first material expression be destroyed; a vanished harmony may yet again inspire the composer, but when the last individual of a race of living things breathes no more, another heaven and another earth must pass before such a one can be again.

WILLIAM BEEBE

INTRODUCTION

DOWN MEXICO WAY

IN THE HIGH MOUNTAINS of Mexicos rugged Sierra Madre Occidental there once lived a woodpecker unlike any othera giant, largest of its clan in the world, whose pounding drumbeat echoed through the primeval forests as it bored into massive pines, hammering on them powerfully for weeks at a time until they groaned, shuddered, and finally toppled with an impact that shook the ground. Victorian explorers dubbed the bird Campephilus imperialis the imperial woodpecker. But it had already been named long before. To the Aztecs, it was cuauhtotomomi in Nahuatl; to the Tarahumaras, cumeccari ; to the Tepehuanes, uagam ; and to the Spanish speakers, the pitoreal .

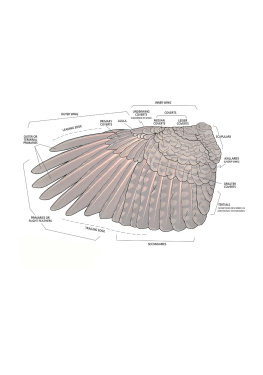

Two feet in length from beak to tail, the imperial woodpecker stood out. It had deep black plumage, except for a white shield on its lower back formed by brilliant snow-white flight feathers, and a big crest (red on the males, black on the females) that curled forward to a shaggy point. Its eyes glowed golden yellow; its long, chisellike bill shone white as polished ivory. And it was noisy, blaring a loud trumpetlike toot as it hitched up a pine trunk, foraging for beetle grubs as big as a mans thumb. Its showy splendor was its undoingthat and the fact that it stayed in tight family groups, often hanging around when one of its group was wounded or killed.

The Huichol, who believe they made the sun themselves, say that the only animals who protected the sun during his first journey across the sky were the gray squirrel and the giant woodpecker. Because of this, the giant woodpecker carries the color of the sun on his scarlet crest.

Norwegian explorer Carl Lumholtz, who spent eight years traveling on muleback down the 900-mile length of the Sierra Madre Occidental in the 1890s, declared that the birds would soon be exterminated. Indigenous people relished the birds taste and believed their feathers and bills held curative powers; curious shooters killed them as a novelty; insatiable loggers moved into their vast forest empire and felled most of the great trees across their range. All played a role in decimating the birds population. By 1956, when amateur ornithologist William L. Rhein from Pennsylvania filmed a lone female imperial woodpecker near a logging camp in the mountains of Durango, the birds were already dangling over the abyss. That single pitoreal was the last of its kind ever documented by a birder, naturalist, or scientist.

Yet its difficult to say for certain that the imperial woodpecker is extinct. Many biologists have already written the birds epitaph, a sad tale of massive habitat destruction and wanton killing. But among the mountain villagers, stories persist of lone pitoreales still flying over the most remote pine forests of the Sierra Madre. Perhaps a handful of the birds do exist and the species could still be savedif someone would just travel through the mountains of northwestern Mexico and talk to people, follow up on leads, and locate a pair of imperial woodpeckers.

Spurring me on my quest was my inheritance of a treasure mapnot for gold or a lost Dutchmans mine, but a cherished topographical map handed to me by a dying man, a noted photographer and naturalist who had himself been given it and had not been able to return to Mexico to explore the areas marked in red on the chart. Carefully preserved for nearly forty years, it showed where imperial woodpeckers had nested in the Sierra Madre as recently as the early 1970s.

The more I thought about this potential discovery, the more I saw myself in the role of the birds tracker. Rediscovering a lost bird as magnificent as the imperial woodpecker, I hoped, would rally scientists, birders, and nature enthusiasts around the world to save this unique species and the habitat it needs to survive. I postponed my search for several years on the advice of Mexican friends, who cautioned, Its far too dangerous now because of all the drug growing and violence in the mountains; better wait till next year. But each year the situation only got worse, and we did not have the luxury of waiting years for things to simmer down. By 2008, I had an overwhelming belief that the imperial woodpecker could be savedbut only if we acted immediately.

The Sierra Madre has always been wild, from the time of the Aztecs to the rule of the Spanish to present-day Mexico. It has always been impossible to govern. Although the mountain range starts less than a hundred miles south of the United States border, it seems worlds away, locked in a distant time. Rugged, remote, and dangerous, it is haunted by the ghosts of martyrs and outlaws, ancient and modern, by legends of lost treasuresand by the imminent loss of its natural treasures, found nowhere else.

The mountains are high, nearly ten thousand feet above sea level along much of their length with even higher peaks, and cut through with deep barrancas , or canyons, one of which is deeper than the Grand Canyon. There the Tarahumara (or Rarmuri)those magnificent long-distance runners who think nothing of racing 150 miles or more nonstop through the mountainsresisted all efforts to colonize them and maintained their stone-age existence well into the twentieth century. And there the last free Apaches (who had fled to the Sierra Madre after Geronimo surrendered to US Brigadier General Nelson A. Miles in 1886) held on into the 1930s, in roving bands, attacking settlers who encroached on their land. And there legendary Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa fled after his daring 1916 raid into New Mexico, successfully evading capture by ten thousand US troops sent on a punitive mission by President Woodrow Wilson. No doubt Villa and his men saw the dust of the American cavalry billowing up from fifty miles away, like a dirty cumulus cloud, into the dry, clear air of the high-mountain plateaus, giving the rebels plenty of time to disappear without a trace into the deep barrancas of the Sierra Madre.

Next page