Jonathan Smith was educated at Christ College, Brecon and St Johns College, Cambridge, where he read English. Since then he has been a full-time schoolmaster, teaching in Scotland, in Australia and at Tonbridge, where he is now Head of Humanities.

His first novel, Wilfred and Eileen , was made into a BBC TV serial. He has written four more novels, a cricket book and a television play. Over the last fifteen years he has also established a reputation as one of the most distinguished contemporary radio dramatists.

Wilfred and EileenThe English LoverIn FlightCome Back

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-1-4055-1999-1

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright Jonathan Smith 1995

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

www.hachette.co.uk

for David Evans

&

the Evans family

Contents

That morning, sitting in his spacious study in Castle House, Dedham, Sir Alfred Munnings opened a letter. It was from his old friend, Dame Laura Knight.

16, Langford Place,

St Johns Wood,

London

27th April 1949

Dear A.J.,So youre really really going to do it tomorrow? Is it wise? Is it for the best? And why at the banquet? Wont it open up old wounds?Whatever, Ill be listening.With love,Laura.

It was time for the Presidents big speech. The tapping, the call to order, was pretty close to his right ear so he had no problem hearing it, and it was clear and crisp enough for everyone sitting at the top table. But then those about to speak in public as youll know if youve ever done it are always on the edge of their seats, waiting for the moment to arrive, picking at their food, wanting the lavatory, as dry-mouthed as jockeys lining up for the start at Newmarket, all tensed up and ready for the off, and conscious that the eyes of the world are about to be on them.

And, in the Presidents case, thousands of ears.

Not that he was nervous. Not a bit of it. If he had been nervous he would have written the whole speech out, wouldnt he, instead of just jotting down a couple of phrases on the back of his menu while enjoying his dinner to the full. Food and drink, the President always maintained, were there to be enjoyed, and the truth was he was looking forward to this speech, to his swansong: he knew what needed to be said to the assembled company and, by God, he was going to say it.

He was under starters orders.

But!

But, the table-tapping, while loud enough for him, was little match for that large gallery full of all-male banter, and no match at all for the distant, well-oiled laughter which rose to the ceiling with the cigar smoke. The younger academicians on the far tables, who had half heard the toastmaster tapping, pretended, in the time-honoured way, that they had not; and when he was sitting in their place many years ago, the President used to do the same thing, employ the same delaying tactics, only a damn sight worse. So, seeing the distant diners were not going to shut up for that genteel top table tapping, he turned round and told the toastmaster to try again, only this time to put a bit of beef into it. And the toastmaster, a man of solid muscle and bone, took the President at his word and fairly hammered the gavel. He hammered it slowly and loudly, with more than a bit of come-on-gentle-men-now-please.

And that, the extra volume plus the emphatic pauses, did the trick. Even the rowdiest table fell silent; and once the lull was established, the toastmaster, resplendent in red, puffed out his barrel chest and projected his voice full blast over everyones heads, past the paintings hanging two or three deep on the walls, through the mahogany doors and out into Piccadilly itself.

Your Royal Highness, he intoned and that word Highness helped to do the trick, bringing a respectful hush Your Excellencies, Your Graces, My Lords and Gentlemen Pray Silence for the President of the Royal Academy, Sir Alfred Munnings.

Yes, thats him!

Pray Silence for the second son of a Suffolk miller, a son of the soil, but then Constable, the great Constable, was the son of a Suffolk miller too, and who wouldnt be as proud as Punch to follow in his footsteps?

There was, too, something about the toastmasters style that the President liked. Good toastmastering, he always maintained, was like gunnery practice: you cleaned the barrels, you slammed in the shells, you got the trajectory right, and then you discharged a deafening salvo at the enemy. Take aim, fire! and the enemy were brought down. Enemy? At a banquet in Burlington House?

What enemy?

But the enemy were there all right, and in numbers.

As the toastmaster intoned his phrases, the President savoured each and every word. He enjoyed each e-nun-ci-ated syllable. Now that , he said to himself, is how to introduce a chap, straight from the shoulder, no mumbling, no beating about the bush.

Your Royal Highness and there indeed was the Duke of Gloucester on his right, more or less upright if rather the worse for wear

Your Excellencies and there were ambassadors from God knows which country at every table, including some Turk or other, Mr Aki-Cacky, on Top Table

Your Graces yes, including the Archbishop of Canterbury himself whod just been up on his feet wittering away mixed up with the odd Admiral and Field Marshal, he could see old Monty at the end of the table. Not to mention loads of lords and plenty of gents, plenty of boiled shirts and stuffed shirts, plus a sprinkling of pansies who couldnt tell a decent painting from a pool of horse piss.

No, steady on now, Alfred, he said to himself, careful, old boy, youre not in The Coach and Horses now, youre in civilised company, surrounded by The Great and The Good, and theyre here for a slap-up do and theyre also here, Alfred, to hear your Retiring Presidents speech and, by God, theyre going to get it!

On the toastmasters final words Sir Alfred Munnings there was some kind of welcoming applause, mostly from Winston and those close by on top table, but enough in all conscience to suggest some kind of recognition of all he had done as President. As the applause died down, Sir Alfred took one more gulp of wine, a bloody good claret hed selected himself, and checked his flies. All secure there, he stood up.

The banquet was in Gallery Three, Burlington House, Piccadilly, and the place was jam-packed with one hundred and eighty diners. The President ran his eye around the candle-lit tables, then placed both his fists, knuckles down, on the white tablecloth. It was a position he liked to adopt when speaking. Not only did it take some weight off his dicky leg, but the stance also (he felt) suited his attacking style.

So, here he was.

And there they were.

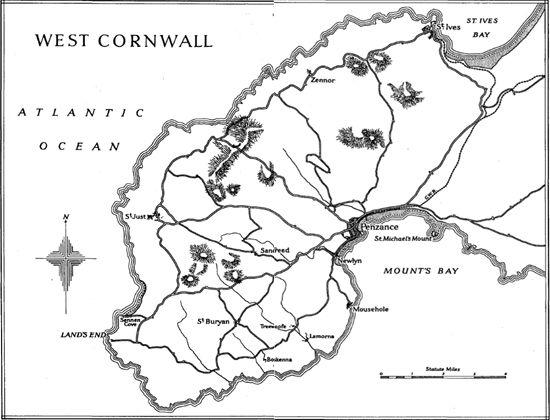

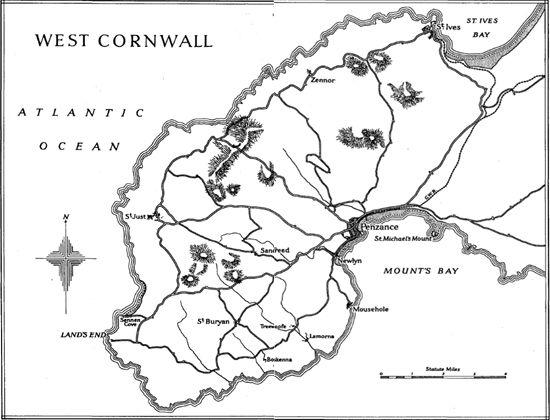

The President faced the Academy; he would not be presumptuous enough to say his Academy. And he faced them with the nation listening on the wireless, thousands of good people from John OGroats to Lands End had turned on their sets, ordinary folk who liked to hear the simple truth spoken in simple plain English.

So, the truth it was to be.

Your Royal Highness, he began slowly, My Lords and Gentlemen. As was his wont, he took his time over each syllable. After a good evening he always maintained it was only sensible to take your time; it was always best to walk your horse home nice and slowly through the lanes. Hurry along, as hed found to his cost, and you could go arse over tip. The trouble was, though, not only was he slow, he was too slow, and without meaning to, his voice caught some of the toastmasters tone.

Next page