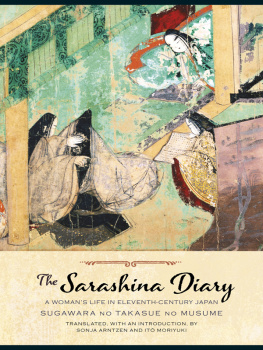

The Sarashina Diary

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

TRANSLATIONS FROM THE ASIAN CLASSICS

Editorial Board

Wm. Theodore de Bary, Chair

Paul Anderer

Donald Keene

George A. Saliba

Haruo Shirane

Burton Watson

Wei Shang

The Sarashina Diary

A WOMANS LIFE IN ELEVENTH-CENTURY JAPAN

SUGAWARA NO TAKASUE NO MUSUME

TRANSLATED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY

SONJA ARNTZEN AND IT MORIYUKI

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53745-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, 1008 author.

[Sarashina nikki. English]

The Sarashina Diary : a Womans Life in Eleventh-Century Japan / Sugawara no Takasue no Musume; translated, with an introduction, by Sonja Arntzen and It Moriyuki.

pages cm. (Translations from the Asian Classics)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16718-5 (cloth : acid-free paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53745-2 (e-book)

1. Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, 1008Diaries.

2. Authors, JapaneseHeian period, 7941185Diaries.

I. Arntzen, Sonja, 1945 translator. II. Moriyuki, It, translator.

III. Title.

PL789.S8Z4713 2014

741.5973dc23

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Columbia University Press wishes to express

its appreciation for assistance given by the Japan Foundation

toward the cost of publishing this book.

Columbia University Press wishes to express

its appreciation for assistance given by the Pushkin Fund

toward the cost of publishing this book.

COVER IMAGE: Detail from Azumaya I, in The Tale of Genji Scroll.

( Tokugawa Art Museum Archive/DNP Art Communications)

COVER AND BOOK DESIGN: Lisa Hamm

CONTENTS

SONJA ARNTZEN

SONJA ARNTZEN

SONJA ARNTZEN AND IT MORIYUKI

IT MORIYUKI

SONJA ARNTZEN

T he Sarashina Diary (Sarashina nikki, ca. 1060) records the life of a Japanese woman from the age of thirteen to sometime in her mid-fifties. Rather than a daily account of events in the writers life (as the term diary might suggest), it focuses on moments of personal meaning, often centered on the composition of a thirty-one-syllable waka poem. The author, Sugawara no Takasue no Musume, was a direct descendant of Sugawara no Michizane (845903), one of the most distinguished literary figures in Japanese history. The Sarashina Diary has a long history of appreciation in Japan, with the first annotated text appearing in the thirteenth century. In the modern period, it was accorded the status of a classicthat is, one of the works representing the golden era of Japanese classical literature, the mid-Heian period (early tenth to eleventh century). During this period, women writers had the domain of prose writing almost to themselves, and they produced numerous works of sophisticated self-writing as well as fiction. Indeed, the surviving works by women in the mid-Heian period comprise the earliest substantial body of womens writing in the world. The Sarashina Diary was written after the other major autobiographical works by women, and it displays a subtle awareness of its predecessors.

It is unusual among native Japanese scholars of classical Japanese literature for the attention he has given to English-language scholarship on classical texts in general and the Sarashina Diary in particular. Moreover, he has made an effort to write papers in English on these texts and to present them at conferences in North America. We met at just such conference in 1998. Then, about nine years ago, It proposed that he and I do a new translation of the Sarashina Diary. He was keen to see a new translation of the work in English and to share his perception of the text with an English-reading public.

Just a few years earlier, I had completed the translation and study of another mid-Heian womans autobiographical text, the Kager Diary, and thus felt prepared for the task. The animated conversations that It and I had had at conferences in the past indicated that we had compatible views of Heian womens literature, enough alike for easy understanding and enough different to be stimulating. Another inspiration for my participation in the project was my fresh view of the text from Edith Sarras study of Heian diaries, Fictions of Femininity: Literary Inventions of Gender in Japanese Court Womens Memoirs. In this work, Sarra devotes a lot of attention to the Sarashina Diary, and her translations of excerpts for analysis reveal an utterly different text from the one I knew only from previous translations. Her work made me want to study the original for myself, so It and I began.

This project has been a mutual collaboration from start to finish. We did most of the work during brief periods every year when we could get together, either in Japan or on Gabriola Island, Canada, where I now live. My responsibility was creating the English rendering of the original text, and Its was explaining the problems of the text and guiding our interpretation. In our original plan, It was going to write the introduction, which I would translate. But because our understanding of the work evolved in conversation with each other, in the end it seemed appropriate to compose the introduction together. Although the foundation of the introduction rests on Its lifetime of research on the text, the articulation of our interpretation of the text has been significantly inflected by me.

Our approach focuses on the diary as a literary creation rather than an unmediated record of the authors life, yet at the same time we are deeply interested in the author herself. Most of all, we see her as an artist who creates different personae in this work to capture the full complexity of her life. Our translation and the accompanying introduction also pay close attention to the thirty-one-syllable poems (waka), which add depth and color to the text. In particular, we are interested in the role of poetry in the orchestration of the texts structure.

It has used the metaphor of a crystal for his overarching view of the diary as a complex and multifaceted work of art. Although the diarys text may appear transparent superficially, it is not a simple transparency. Like the facets of a crystal that reveal different colors, each facet of the text offers different perspectives of meaning, depending on the angle from which it is viewed. Our analyses of specific passages show how they enable diverse readings and how opposite meanings are woven into the text by means of its structure. After years of reading the text together, It and I came up with a second metaphor, that of musical counterpoint, to convey how the patterning of contrasting motifs and intertextual references in the text brings its meta-meanings into play. We hope that together the introduction and the translation help readers, figuratively, see the color and hear the music in Takasue no Musumes remarkable work.