This book is dedicated to J. G. Sherman and Peter Collias

Simon & Schuster Paperbacks

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 1998 by James Chace

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Simon & Schuster Paperbacks Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020

First Simon & Schuster trade paperback edition December 2007

SIMON & SCHUSTER PAPERBACKS and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

Designed by Sam Potts

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Control No.: 98003801

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-4865-2

ISBN-10:1-4165-4865-3

eISBN: 978-0-684-86482-2

P HOTO C REDITS

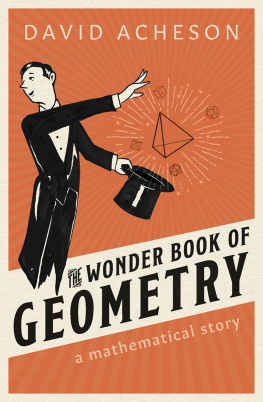

Courtesy David Acheson 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 16, 17, 24

Courtsey Mary A. Bundy 7, 10, 12, 13, 14, 32

George Tames, NYT Permissions 15

AP/Wide World Photos 18, 21, 26, 29

UPI/Corbis-Bettmann 19, 20, 22, 23, 25, 27

Yoichi R. Okamoto, LBJ Library Collection 28

deKun, Inc., courtsey Mary A. Bundy 30

Jill Krementz, courtsey of the photographer 31

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution 33

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE THE CUSTOM OF THE COUNTRY

THE CUSTOM OF THE COUNTRY P RESIDENT H ARRY S. T RUMAN knew he was a discredited man. On the day after the congressional elections of 1946, his party suffered its worst defeat since 1928, losing both the House and Senate to Republicans. Under his leadership, Democrats lost badly in New York, California, Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Illinois and did poorly in the border states. The New Deal coalition that FDR had put together appeared shattered. Arriving from Kansas City at Washingtons Union Station on a depressingly gray November morning, Truman walked off the train, silent but smiling, and found no one there to greet him.

Politics is an unsentimental business, and the president understood that politicians could not afford to be tainted by too close proximity to failures. It was therefore with some astonishment that he saw there was, after all, someone standing on the platform to meet him. In his elegantly tailored topcoat and homburg was his under secretary of state, Dean Gooderham Acheson. The president was absolutely delighted to see him and asked him back to the White House for a drink.

Dean Acheson, on the other hand, was perplexed and deeply distressed at the absence of any high official from the government save himself. As he later recalled, It had for years been a Cabinet custom to meet President Roosevelts private car on his return from happier elections and escort him to the White House. It never occurred to me that after defeat the President would be left to creep unnoticed back to the capital. So I met his train. To my surprise and horror, I was alone on the platform where his car was brought in, except for the stationmaster and a reporter or two.

For Truman, the greatest political value was loyalty. Achesons uncomplicated display of fealty to his chief was a loyalty as much to the office of the presidency as to the man. But it helped to forge an iron bond between the two men over the next seven years that led to the creation of new institutions so powerful that they came to definefor Americans at home, for allies and adversaries, for good and for illan American international order.

Both men were products of small-town life, both were men of action, filled with vitality and endowed with a strong sense of humor, and both were without guile or self-importance. Harry Truman, self-educated, devoted to his wife and daughter, easy with his poker-playing cronies, never really had a close male friend, until, toward the end of his life, he found one in Dean Acheson, who on the surface seemed the most unlikely of choices.

Improbable friends, Truman the bookworm and Acheson the rebel. For Acheson was rarely at peace with the world: he was quick, often impatient, too much at odds with superficial codes of conduct. Tall, slim, dashing, and seemingly remote, the personification of the American notion of a British diplomat, Acheson was, in fact, a gregarious and outspoken man who could easily wound those who he felt were inauthentic. He was said not to suffer fools gladly; in fact, he suffered them scarcely at all.

Like Truman, Acheson believed that most problems could be solved with a little ingenuity and without inconvenience to the folks at large.

When Acheson accompanied the president back to the White House, he seemed to bring a change to the Truman presidency. In a sense he came to the White House to stay. That very afternoon he met with members of Trumans personal staff and urged them not to let the president call a special session of Congress in order to confirm petty political appointments before the new Congress could take over.

The incorruptible figure of Acheson in some sense symbolized the transition from the first phase of the Truman presidency, with all its parochialism and tacking, to the second, more heroic period.

It was Acheson, first as under secretary, then as secretary of state, who was a prime architect of the Marshall Plan to restore economic health to Western Europe, who refashioned a peacetime alliance of nations under the rubric of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, who crafted the Truman Doctrine to contain any Soviet advance into the Middle East and the Mediterranean. It was Acheson who had already been instrumental in creating the international financial institutions at Bretton Woods that helped ensure global American economic predominance. And it was Acheson who stood by Truman in deciding that the United States must respond to the North Korean invasion of South Korea, who urged the firing of General Douglas MacArthur for insubordination, and who stood up to the vilifications of Senator Joseph McCarthy.

Above all else, it was Acheson who created the intellectual concepts that undergirded Trumans decisions, who had the clearest view of the role America might play in the postwar world, and who possessed the willpower to accomplish these ends. Not long after Acheson joined Truman at the White House on that bleak November day in 1946, the administration finally found its footing in the international arena. With Acheson at or near the helm, its policies started to show a breadth of conception, a buoyancy, and a boldness of action that had not been seen in foreign affairs in peacetime in this century.

Although Acheson was a convinced anti-Communist, he rejected extremes and was far from being a Cold Warrior at the end of World War II. On the contrary, he sought cooperative agreements with the Soviet Union as a great power that had shared in the victory over the Axis with the United States and Great Britain.

But when he determined that it was imperative to contain an expansionist Soviet Union, he was prone at times to employ a rhetoric of anticommunism that, in his own words, made his arguments clearer than truth in order to get them accepted by the Congress. These were Faustian bargains, however, and during his last years in office Acheson would be savagely attacked by the conservatives as an appeaser of an ideologically threatening Soviet Union.

Next page