For Josh, because words dont ever fit

even what they are trying to say at

THRILL PARTIES EVERY NIGHT over on Hussel Street. That tiny house, why, its 600 square feet of percolating, Wurlitzering sin. Those girls with their young skin, tight and glamorous, their rimy lungs and scratchy voices, one cheek flush and cmon boys and the other, so accommodating, even with lil wrists and ankles stripped to pearly bone by sickness. They lay there on their daybed, men all standing over round, fingering pocket chains and hands curled about gin bottle necks. The girls lay there on plump pillows piled high with soft fringes twirling between delicate fingers, their lips wet with syrups, tonics, sticky with balms, their faces freshly powdered, arching up, waiting to be attended to by men, our men, the citys men. What do you do about girls like that?

OCTOBER 1930

He was a kind husband. You couldnt say he wasnt kind.

He found her a rooming house and paid up three months, all he could manage and still make his passage to Mazatln, where he would take up a steady post, his first in three years, with the Ogden-Nequam Mining Company, for whom he would drain fluid thick, yellow as pale honey from miners lungs.

He purchased for her, on credit (who wouldnt give credit to a doctor, even one in a suit shiny from wear), a tea set and a small Philco radio for her long evenings, sitting in the worn rose chair writing letters to him, missing him so.

He purchased for her a pair of kidskin gloves and tie shoes and a soft cloche hat the deep green of pine needles.

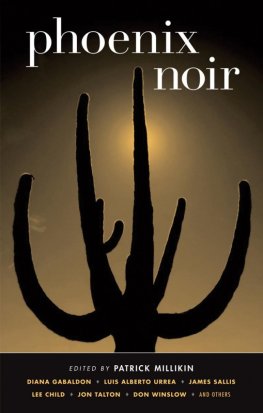

He took her on strolls around the neighborhood so they might look for the one hundred varieties of cactus promised in the pamphlet given to them at the Autopia Motor Court, where theyd spent their first two nights after the long drive from California. He found the cholla and the saguaro and the bisnaga, which had saved the life of many a thirsty traveler who, beaten down by the sun, cut off the spiky top and mashed the pulp within.

He helped her fill out all the papers to begin her new job, which he had found for her. She would start Monday as a filing clerk and stenographer at the Werden Clinic. She passed the typing test and the dictation test and Dr. Milroy, the director, who was very tall and wore tinted spectacles and smelled sweetly of aniseeds, hired her right then and there, taking her small hand between his palms deep as serving dishes, as softly worn as the leather pew Bibles passed through three generations hands in the First Methodist Church of Grand Rapids, and said, My dear Mrs. Seeley, welcome to our little desert hideaway. We are so glad you will be joining us. I have assured your husband you will be happy here. The entire Werden community welcomes you to its bosom.

On Sunday night, late, he packed his suitcase for his long trip, first to Nogales, then Estacin Dimas, then ninety miles on muleback to Tayoltita. The mining company didnt care about revoked medical licenses. They were eager to have him. But, with her, he had always been clear: where he was going was no place for a woman. He would have to go alone.

When he was finished packing, he sat her down on the bed and spoke softly to her for some time, spoke softly of his grief in leaving her but with solemn, gravely worded promises that he would return in the spring, would return by Easter, arms filled with lilies, and with all past troubles behind them.

And on Monday morning at seven oclock her husband, having made all these arrangements, walked her to the trolley and kissed her discreetly on the cheek, his chin crushing her new hat, and headed himself to the train depot, one battered suitcase in hand. As she watched him through the trolley window, as she watched him, slope-shouldered in that ancient brown suit, hat too tight, gait slow and lurching, she thought, Who is that poor man, walking so beaten, face gray, eyes struck blank? Who is that sad fellow? My goodness, what a life must he lead to be so broken and alone!

THE DOCTORS AT THE CLINIC were all kind as could be, and all seemed concerned that she felt comfortable and safe in her rooming house. They left a cactus blossom on her desk as a welcome gift and offered her a tour of the State Capitol, pointing proudly to its copper dome, which could be viewed from the clinics third-floor windows. Right away, Dr. Milroy and his wife began inviting her to Sunday dinner and she heard again about the one hundred varieties of cactus she might see around town and she heard that no other place in the world is blessed with so many days of sunshine and she heard how, as she must know, the desert is Gods great health-giving laboratory. Then, at the end of the evening, Mrs. Milroy always sent her home with a dish steaming over with creamed corn casserole, a knot of pork, sweet carrots in honey glaze.

Youre nothing but a whisper of a girl. But youll need something on your bones for when you start your family. When Dr. Seeley comes back, you know hell be ready for a son. Am I right?

She smiled, she always smiled. Dr. Seeley hadnt talked of sons, of children since before the first monthlong stretch at St. Bartholomews narcotics ward. Theyd never talked much of babies, even as she was sure when she married three years, seven months back that shed be near the third time large with child by now, like all the girls she knew.

IT WAS FRIDAY, her fifth day at the clinic, and she had seen Nurse Louise stalking the halls more than once, stalking them, a lioness. A long-limbed girl with a thick brush of dark red hair crowning a pale, pie face, painted-on brows thin as kidsilk and a tilting Scotch nose. When she walked, her hips slung and her chest bobbed up round apples and the men on the ward took noticemy, how could they not? She was not beautiful, but she had a bristling, crackling energy about her and it was like she was always winking at you and nodding her head as if saying, always, even when stacking X-rays, Cmon, sweet face, cmon.

And now here was Nurse Louise dropping herself, hard, in the chair across from Marion in the luncheon room. She smelled like licorice and talcum powder.

Thats for beans, kid, she said, jabbing her thumb dismissively at Marions jelly sandwich. Have a hunk of my brown bread. Ginnythats my roommateswabbed it up good with plum butter. Tell me that aint the stuff.

And Marion took the wedge offered her and it smelled like Mothers kitchen even if Mother never made any bread but white or sometimes milk-and-water bread. And the plum butter, well, that stung sweet in her mouth since she hadnt had much but bean soup since Dr. Seeley left her, left her all alone five days past.

Whats your name, answer me now with your cakehole plug full, she said, laughing. Im Louise Mercer. Ive been here going on a year now, so I guess theres not much I dont know. Im happy to show you all the dials and knobs and pulleys, if you like. So nothing crashes down on that slippery blond head of yours.

Well, Im Marion. Marion Seeley, she finally got out, eyeing a dab of butter still smeared on her thumb.

Go on, Marion. Louise smiled, nodding toward the pearly butter. We dont believe, none of us, in wasting fine things.

SUDDENLY, she was under Louises red-tipped wing and everything became easier. She learned the best place to hang her hat and coat so they didnt smell of disinfectant, the trolley route thatd get her home seven minutes faster and two blocks closer to boot and that you should punch the clock before you even set your purse down each morning.