The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

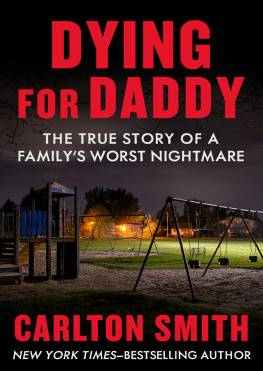

This book is dedicated to the residents of Union, South Carolina, who came together in tragedy and, by their unbending love and faith, showed the nation the true meaning of community. In their hearts, Michael and Alex Smith will live on always.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My thanks to People Managing Editor Landon Y. Jones, my editors, Roger Wolmuth, Joe Treen and Jack Friedman, and People correspondents Don Sider and Gail Wescott. I also want to express my sincere gratitude to People Senior Writer Cynthia Sanz for editing this book and for all of her support.

The headlights on the burgundy Mazda Protege cast an eerie glow on the dark waters of John D. Long Lake. Just before nine P.M. the lake was deserted. Those who fished catfish from the basins murky depths had left hours earlier, piloting their johnboats to the shore as darkness fell. Now, the only noise was the hum of the Mazda as it paused atop a seventy-five-foot-long boat ramp. Moments later, the gravel beneath the Mazdas wheels would crunch as the car slowly began its descent.

It was October 25, 1994, a mild night in Union, South Carolina. In the summer months, the lake was a popular gathering place for the townspeople. Just after daybreak and right before dusk, its banks were dotted with fitness walkers marching along the side of the woods near the lake, nodding and calling out greetings to each other.

During the afternoons, teenagers and couples, and most of all, families with young children covered its shores. But as temperatures dropped and the bland fall breezes turned chilly, the crowds began to thin. Even when the sun shone brightly, there was school and homework, so many more commitments as winter approached.

And so the steady tide of cars continued along Highway 49, connecting Union and Lockhart, with fewer and fewer making the turn and passing the green sign that welcomed guests to John D. Long Lake. Most evenings, once darkness enveloped the lake there would be no visitors at all, no sounds again until daybreak.

Yet that night in Union, South Carolina, at John D. Long Lake, a visitor named Susan Smith fractured the quiet.

It was about 8:45 P.M. and Susan sat motionless in the Mazda, her hands clutching the steering wheel. She could hear the rhythmic breathing of her two children asleep in the back seat, their energy finally drained. Michaels third birthday had been just two weeks earlier, and Alex, fourteen months, had recently taken his first steps alone. How they laughed and tumbled through each day, learning and exploring together.

But now, there was only sleep, the deep, tranquil kind a parent expects in a warm, moving car at night. Indeed, it had taken only a few minutes after Susan buckled them into their car seats, before they had both settled down and drifted off.

Susan Smith, twenty-three, shifted the Mazda into neutral and the car slowly began to roll down the ramp. She stepped on the brake. Then, she pulled the emergency brake up with a swift tug. She stepped outside and stood on the banks of the John D. Long Lake.

She had a decision to make.

It didnt matter how long she stood therethe children were asleep and no one was waiting at home for Susan. She and her husband, David, were amid divorce proceedings. Married at nineteen, they had thought their marriage would last a lifetime but it hadnt worked out that way. In August, David moved out of their small redbrick ranch.

Susans boyfriend, Tom Findlay, wasnt waiting either. After a brief courtship he had decided that Susan was a little too needy for him, and that he was not ready for a commitment, especially not to a woman with two young children. Hed ended their relationship one week earlier.

On the way to the lake that night, Susan had driven by the Winn-Dixie, the local supermarket, where David worked as an assistant manager. She passed the road that led to Judy and Carol Cathcarts day-care center, where Michael and Alexander played on swing sets and gazed out at the cows grazing in the nearby field. She went by Veterans Park, where she occasionally took her sons to feed breadcrumbs to the ducks in the pond. She drove by Conso, the decorative trimmings factory where she worked as a secretary. She wasnt far from the homes of her mother and stepfather, Linda and Bev, and her brother, Scotty and his wife, Wendy.

They were places and people she once cared about, but now there was nothing, only emptiness and pain. The losses in her life had finally numbered too many; shed felt the sting of rejection from too many men. The responsibilities of motherhood overwhelmed her.

She wondered if death would relieve the ache inside her.

Susan Smith looked out at the blackness of the lake and it was a blackness that consumed her. She wanted relief, a respite from the misery, the loneliness.

She would take them with her, those sweet little ones in the back seat. They would suffer less with her, she believed, than left on their own in a compassionless world without her.

But something inside her prevented Susan from surrendering herself to the blackness. Standing at the lake that night she discovered she didnt want to die: all she wanted was to break from the heavy burden she felt so overwhelmed her. For a moment, nothing else matterednot even the love Susan had for her children.

In that instant, Susan Leigh Vaughan Smith, whom everyone would later recall as a pretty, intelligent, popular, churchgoing young lady, made the decision that would catapult her into a worldwide spotlight, an odious decision that she would relive again and again.

All the innocence of childhood ended in a moment. Susan reached inside the car and somehow resisted the soft, guileless faces of her little boys.

She alone knows if she said good-bye.

What she did next is what will never be forgotten, or understood. Susan Smith pressed the head of the Mazdas emergency brake and gently lowered the handle down. As the car began to roll, Susan gave the door a push. It slammed shut, sealing the Protege and the fate of Michael and Alexander Smith with a hollow thud.

If Susan Smith stood at the shore of the lake and watched, she likely saw the car drift into John D. Long Lake. Because it entered the dark waters slowly, it didnt submerge immediately. For a few minutes it seemed as if it would just remain there, bobbing endlessly, peacefully. But of course it could not. And as the burgundy Mazda gradually filled with the water from John D. Long Lake, the trust of a mothers heart drowned.

But now, it was too late for regrets. Standing on the banks of the lake Susan Smith made her next tortured choice: self-preservation. She turned her back on the sinking car and began to run up the road, screaming. The lights of a small house flickered in front of her.

The story she was about to tell would kindle the sympathy of a nation. It would raise doubts in some and bruise a community that prided itself on racial harmony. And it would introduce to the world the faces of two little boys and mobilize a vigorous search to bring them safely home.

When the truth was at last revealed, the world would imagine what happened the night Susan Smith took the lives of her children, replaying the scene at the lake in Union, South Carolina in their minds again and again. Worst of all, both those who knew Michael and Alexander Smith and those who had never met them would hear the sounds inside the Mazda Protege resounding in their hearts for a long time to come.