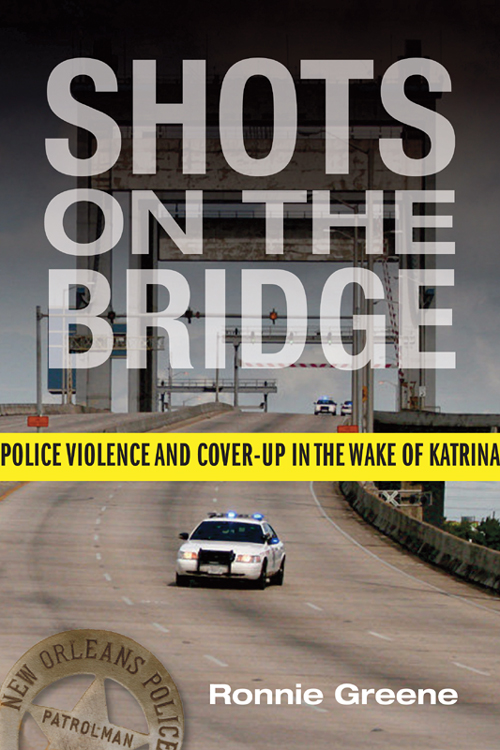

To the families who suffered unspeakable loss atop the Danziger Bridge, September 4, 2005, and in honor of their quest for justice

And to Abby and Emma and Beth, my sun and my moon and my soul

PROLOGUE

ON THE BRIDGE

IT IS 9:00 A.M. ON THE FIRST Sunday after Hurricane Katrina, September 4, 2005, and azure skies greet a city buried in water, panic, and death. New Orleans Police Department officers are gathered at their makeshift nerve center, the Crystal Palace banquet hall at Chef Menteur Highway and Read Boulevard, fueled up on Vienna sausages and bracing for another day of hell. The Crystal Palace CP insignia is scripted in cursive atop the building faade, an elegant touch capping a structure that rises on a crest set back from the highway, apart from used auto-parts stores, fast-food chicken drive-thrus, and quick cash payout hubs. The Palace features winding staircases, crystal chandeliers, a streaming water fountain, and a ballroom grand enough to hold seven hundred people. Its romantic atmosphere is perfect, its proprietors say, for the loveliest of weddings. Now it is ground zero for law enforcement in a swath of eastern New Orleans flooded in despair.

Six days earlier, Hurricane Katrina thrashed lower Louisiana in the eerie early hours of Monday morning August 29, an onslaught that began with menacing winds that held the citys inhabitants in lockdown, and then biblical floods. Fifty minutes after Katrinas landfall southeast of New Orleans, a levee collapse at the Industrial Canal sent oceans of water pouring into neighborhoods through a breach two football fields in width. In twenty-three minutes, water rose to fourteen feet in height. City 911 dispatchers, fielding six-hundred emergency pleas for help in those initial twenty-three minutes, began sobbing between calls, helpless to aid the voices on the other end of the line. Adults floated toddlers in plastic buckets, searching for safe harbor. Personal boats piled up against bridges like toys flung against a wall. Survivors climbed to the top of minivans and rode where the waters took them as frantic hangers-on raced to grab a piece of the roof as a post-hurricane lifeline. A police car was buried by the waters, the red lights on its roof barely visible. This whole place is going under water! a storm chaser uttered as he contrived to navigate his way out of New Orleans and its failed levees.

New Orleans was profoundly unprepared for Katrina. The city had no plan in place to aid the one hundred thousand souls who stayed behind as the hurricane advanced, and as the storm swallowed homes and buried victims, the police chain of command collapsed. There were no rules in place other than Wait it out and, when the winds wind down, begin your patrols, said Eric Hessler, a former narcotics officer who returned days later to help search for bodies. Basically they gave you nothing. You might see a case of bottled water. Other than that, you were on your own.

Each day after Katrinas landfall, the officers of the New Orleans Police Department ventured into the citys streets with two core missions: To save the residents who, by poor judgment or misfortune, made the choice to stay in their homes as the mayor practically begged his constituents to flee Hurricane Katrinas approach. And, to accost the opportunists and window smashers who turned the hurricanes misery into a wheel-of-fortune grab from stores stocked with goods on their shelves but no one at the cash register. Officers headed into New Orleanss streets prepared for combat, occasionally passing dead bodies floating face down, and on high alert for the desperate or the deranged. Some officers toted their own AK-47s, keeping their assault rifles wedged in the front seat beside them as they navigated the streets in vast rental trucks commandeered after Katrina. Like the rest of New Orleans, many officers were prisoners of the hurricanes wakebarely connected to the outside world, sustained by shared rations, and searching for sleep in the pitch-dark nights.

In this new world, the Crystal Palace became the departments command center for a pocket of east New Orleans that instantly felt like a war zone. The Palace stood on the highest ground in that section of the city, making it a home port for police. Officers slept on its carpeted and gleaming floors, on chairs, on any space they could find each night. In the morning, they gathered underneath the chandeliers and staircases to plot their days patrols.

This Sunday morning, the sun announcing itself overhead, the officers await their command.

One, Robert Faulcon Jr., at forty-one, is older than most, and a black former military man and son of a minister who sent his pregnant fiance away to higher ground as he stayed behind to report for duty. Before this day, he had never fired his police firearm while on patrol. Another officer, pale skinned, black haired, had beat back a second degree murder charge three years earlier in the shooting death of a black manand then, like his father before him, Sergeant Kenneth Bowen was a police officer by day and law school student at night. Another young white officer sent his wife and four children to Houston before Katrinas arrival, and then headed into the New Orleans streets each day with his thirty-inch personal assault rifle tucked between the two front seats. Discharged early from the marines, Officer Michael Hunter had twice been suspended by a New Orleans police force noted for leniency when investigating its own.

Over the years, the NOPD had generated a lengthy rap sheet. In the 1990s, one burly black officer, Len Davis, nicknamed Robocop in the housing projects, ran a business protecting cocaine dealers while donning the badge. He also amassed a log of abuse complaints so thick local attorneys likened it to a phone book. Most times, the department and district attorney turned the other wayuntil Robocop, enraged that a young black mother filed an abuse complaint against him, ordered a hit man to kill her. Robocop was a symbol of the NOPD at its most severe, but the departments wayward ways were not limited to one outlaw with a badge.

In 1995 a black female officer and her teenage accomplice took three lives in an armed holdup at a Vietnamese restaurant where she had worked security, killing a white off-duty officer and two children of the proprietors of the Kim Anh restaurant. After the melee, the officer dropped her partner off, heard the 911 call about the shooting, and returned to Kim Anh in uniform. A restaurant worker, cowering for safety in a walk-in cooler during the bloodshed, pointed at Antoinette Frank, the twenty-three-year-old officer. Hired at the NOPD despite scoring low on her psychological exam, Frank today sits on death row.

Fifteen years earlier police found one of their own, a young white officer, dead aside a ditch in the city neighborhood of Algiers, a bullet in his neck. Soon, scores of young black men were whisked into police headquarters, some at gunpoint, where they suffered strong-arm interrogation until police got what they sought: names. Within five days, four black residents were killed by police fire, including a twenty-six-year-old woman, riddled with bullets as she lay naked in her bathtub. The force said it fought fire with fire, killing those responsible for the officers death. Then a black officer turned and unmasked the lies. The victims were unarmed. Activists launched marches at city hall, yet convicting police in their hometown of New Orleans would be no easy task. A state grand jury refused to indict officers in the so-called Algiers 7 case. A federal grand jury did return an indictment: not for the deaths but for the roughhouse treatment of witnesses that violated their civil rights. When officers were finally put on trial, it was in Dallas, not New Orleans. Three white officers went to prison.