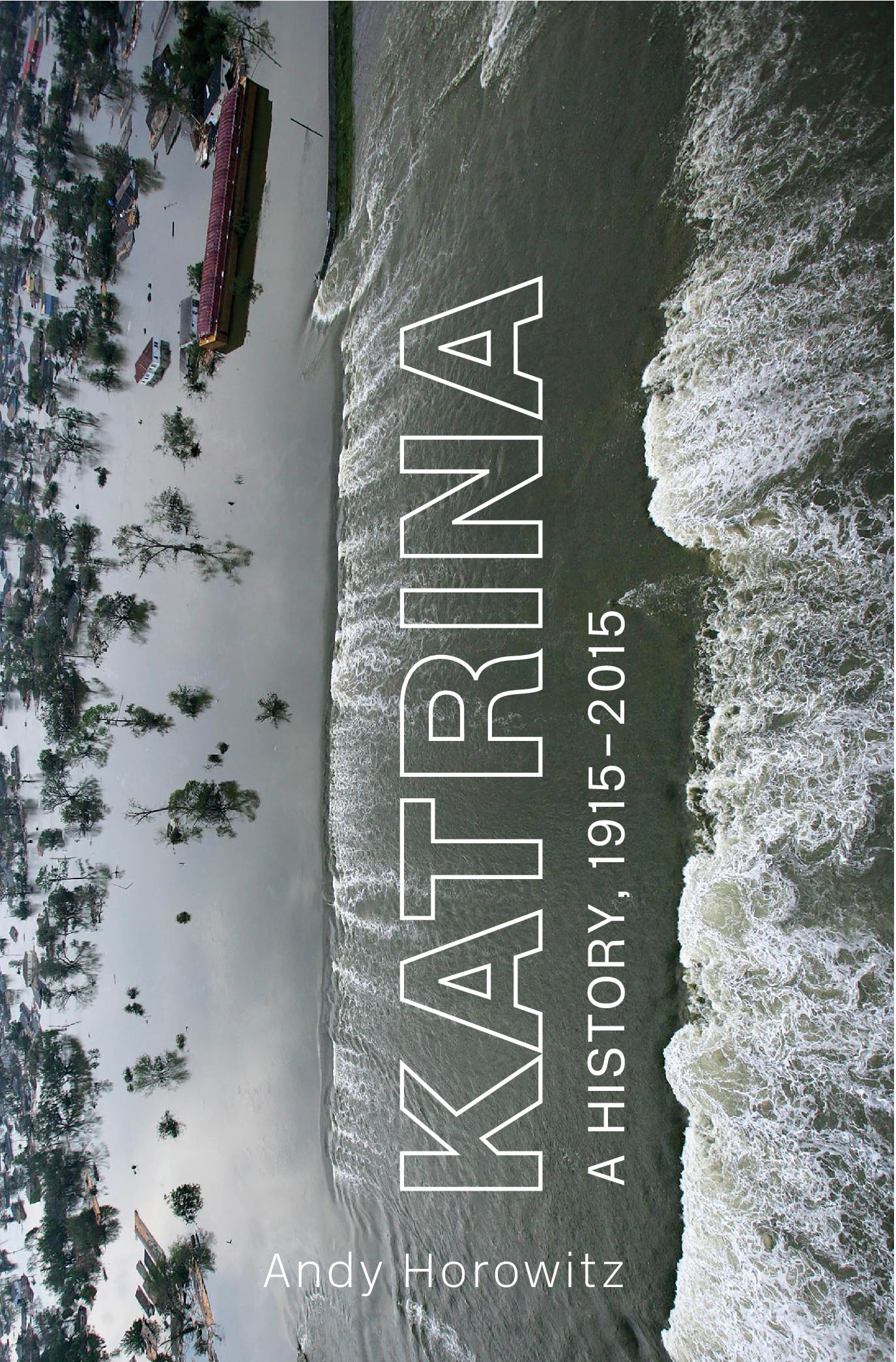

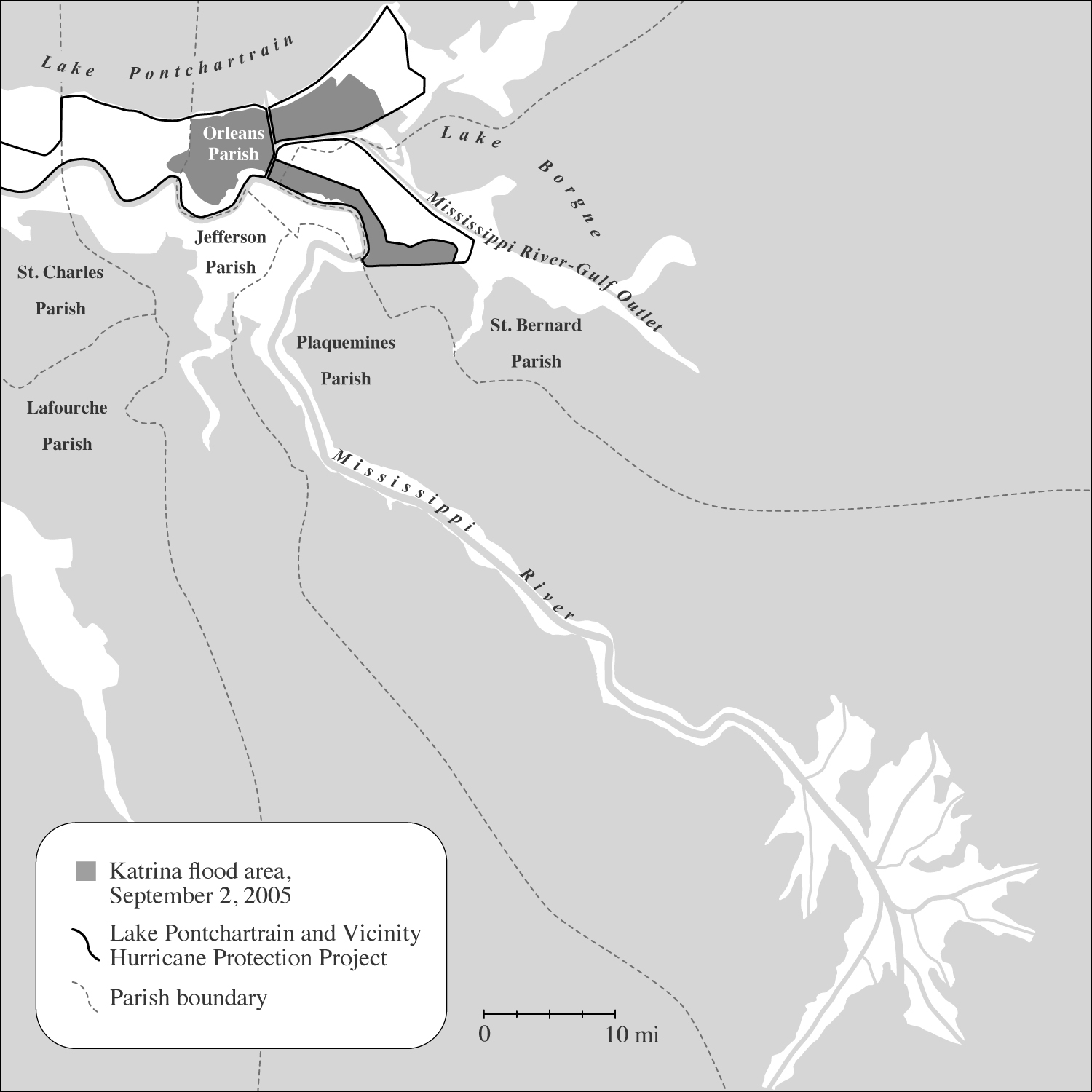

Katrina flood area, September 2, 2005.

Katrina flood depth, September 2, 2005.

On September 29, 1915, at the muddy end of the Mississippis farthest reach into the Gulf of Mexico, one hundred miles downriver from New Orleans, an unnamed hurricane made landfall. An anemometer recorded wind gusts of 140 miles per hour there, at the town of Burrwood, Louisiana, where on easier days several hundred members of the Army Corps of Engineers lived in orderly cottages and worked to keep the shipping canal at the rivers mouth clear of sediment.

But meteorology is not meaning. On their own, these data reveal little about how the storm might have mattered to people, or how they might have responded to it. These precise metrics of wind speed, rainfall, and barometric pressure do not trace the shape of life in places that seem, repeatedly, to come under assault from the forces of nature. We need different tools to gauge those times when coincidences of earth, wind, and water upset the course of human events in ways so overwhelming that we name them with a word whose basic meaning suggests that the entire universe is out of joint: disaster.

Consider that during the 1915 hurricane, across the state of Louisiana, 275 people died. Property damage estimates ran to $12 million ($280 million in 2015 dollars). Upriver from Burrwood, only four houses remained standing in the town called Empire. East of New Orleans, in St. Bernard Parish, the settlement of Saint Malo was washed from the map entirely. That village bore the name of Jean Saint Malo, who in the 1780s had led a group of Africans trying to escape from slavery. Eventually captured by Spanish authorities, Saint Malo was executed in 1784 in front of the Cabildo, in the historic center square of New Orleanswhere the hurricane winds had sent pieces of slate flying from the steeple of Saint Louis Cathedral. A foot of water remained in parts of the city for five days. Nonetheless, once the storm passed, many New Orleanians celebrated.

Storm proof! The Record Shows Orleans, the newspaper proclaimed after the hurricane. The mayor quickly rejected outside offers of aid. Surveying the event a month later, the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board, the agency charged with protecting the city from floods, concluded that its new drainage system had passed a defining test. It is safe to say, its report asserted, that no city anywhere in the world could have withstood these conditions with less damage and less inconvenience than has New Orleans. Marshaling statistics from meteorologists like Isaac Cline, the report reasoned that the recent extreme occurrence of wind and rain renders more remote the probability of a repetition of any of these things in the early future.

It was a curious logic in a city that had seen ninety-two hurricanes or tropical storms since its European colonial founding in 1718.

The city they created became one of the most celebrated places in the world. Aint no city like the one Im from! the women in the Original Pinettes Brass Band sang a century later. With its jazz, Mardi Gras, and other iconic contributions to world culture, more than any other place in America, New Orleans called to mind creativity, cosmopolitanism, and love of life.

But today, New Orleans also calls to mind catastrophe. The city drowned when its levee system collapsed on August 29, 2005, killing hundreds of people, destroying thousands of homes, and precipitating not only one of the most horrific moments in modern American history, but offering an emblem for the idea of disaster itself: Katrina. The response to the 1915 storm thus cast a century-long shadow, because the new neighborhoods developed after that storm experienced the worst flooding in 2005.

Usually, we imagine disasters as exceptions. We describe them as external attacks, ahistorical acts of God, blows from without. That is why most accounts of Katrina begin when the levees broke and conclude not long after. But these stories offer a denuded sense of what happened, why, or what might have prevented the catastrophe. Somebody had to build the levees before they could break.

I begin the story of Katrina in 1915 in order to pursue a different idea: that disasters come from within. Disasters are less discrete events than they are contingent processes. Seemingly acute incidents, like the largely forgotten 1915 hurricane, live on as the lessons they teach, the decisions they prompt, and the accommodations they oblige. Their causes and consequences stretch across much longer periods of time and space than we commonly imagine. Seeing disasters in history, and as history, demonstrates that the places we live, and the disasters that imperil them, are at once artifacts of state policy, cultural imagination, economic order, and environmental possibility.

Katrinas causes and consequences reach across a century. The 1915 Sewerage and Water Board report shaped the rationale for developing the neighborhoods that flooded in 2005. Wrangling over fur trapping rights in the 1920s in St. Bernard Parish shaped the legal struggle for offshore oil in the 1940s, which shaped Louisianas economy in the 1950s, the states coastline in the 1970s, and the states Coastal Master Plan to confront land loss in the 2010s. When the Industrial Canal, dredged for shipping interests in 1918, flooded the homes of veterans during Hurricane Betsy in 1965, the memory of sharecropping shaped how African Americans interpreted the Small Business Administration loans they were offered as disaster relief. The memory of Hurricane Betsy shaped how New Orleanians responded when the Industrial Canal broke again under the weight of Hurricane Katrinas storm surge in 2005. The promise of the federal Housing Act of 1937 shaped the claims that residents made for a right of return to public housing in 2007. The Louisiana state engineers dynamited a levee in St. Bernard Parish in 1927, which shaped fears in 1965 and 2005 that politicians had lit another fuse. The mutual benefit associations African Americans developed during Reconstruction to provide burial insurance shaped the Social Aid and Pleasure Clubs that offered Louisiana its most popular metaphor for recovery: the jazz funeral. When Jesse Jackson declared in 2005 that, filled with stranded African American Katrina victims, New Orleanss Convention Center looked like the hull of a slave ship, he was admonishing all who heard him that disasters offer no escape from the past.