A Strange Business

ALSO BY JAMES HAMILTON

Turner: A life

Faraday: The life

Turner and the Scientists

Turners Britain

Turner: The late seascapes

Turner and Italy

Fields of Influence: Conjunctions of artists and scientists, 18151860 (editor)

London Lights: The minds that moved the city that shook the world

Volcano: Nature and culture

Arthur Rackham: A life with illustration

William Heath Robinson

Wood Engraving and the Woodcut in Britain, c.18901990

The Sculpture of Austin Wright

Hughie ODonoghue: Painting, memory, myth

Louis Le Brocquy: Homage to his masters

The Paintings of Ben McLaughlin

Making Painting: Helen Frankenthaler and J. M. W. Turner

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright James Hamilton, 2014

The moral right of James Hamilton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-84887-9-249

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-78239-4-310

Paperback: 978-1-84887-9-256

Printed in Great Britain.

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

This book is for Kate

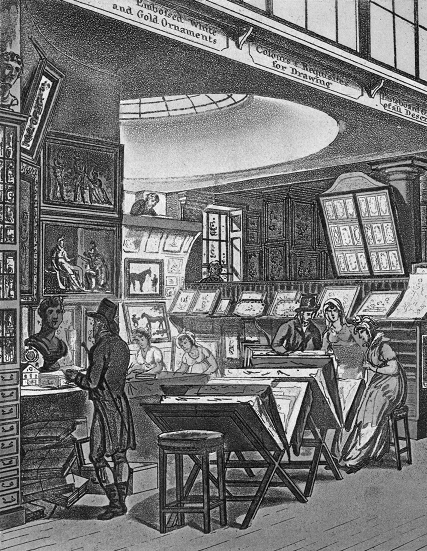

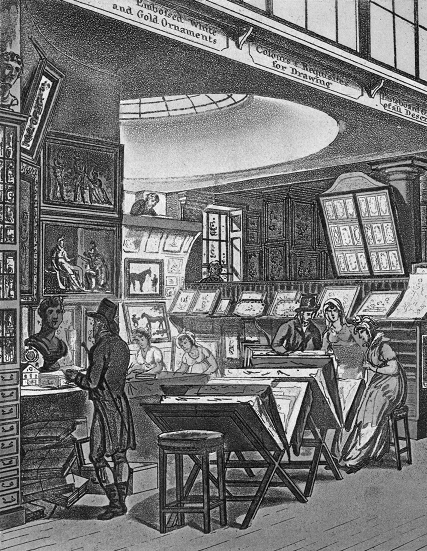

Rudolf Ackermanns premises, The Repository of Arts, in the Strand, London. Etching with aquatint by A. C. Pugin, published by Rudolf Ackermann, 1809.

Detail. (British Library / Robana via Getty Images)

CONTENTS

Painting is a strange business

J. M. W. Turner

FOREWORD AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A Strange Business is the last in an evolving quartet of books that began with my Turner: A Life (1997), continued with Faraday: The Life (2002) and looked more widely at the social background of art and science in the nineteenth century in London Lights: The Minds that Moved the City that Shook the World (2007).

J. M. W. Turner, Mr Turner as he has been known in our house for twenty years, is the thin red line that runs through all four books. He is an occasional presence in Faraday: The Life; he hovers about London Lights; and in A Strange Business he is a constant undercurrent, churning here, surfacing there. Beyond, around and reflected by Turner, the nineteenth is a rich and extraordinary century, a gleaming, oil-streaked, sun-drenched pool. The only way that seemed appropriate for me to approach it was with a running jump and something of a splash.

Those listed here all helped usefully and critically in bringing this book to fruition, and I thank them all warmly: Lucy Blaxland, Felicity Bryan, Julius Bryant, Claire Burnand, Neil Chambers, Robert Chenciner, James Collett-White, Nicholas Donaldson, Zach Downey, Tracey Earl, David K. Frasier, Colin Harris, Colin Harrison, Kurt G. F. Helfrich, Rosemary Hill, Jeannie Hobhouse, Frank James, Andrew Kernot, Stephen Lloyd, David McClay, John Maddicott, Martin Maw, James Miller, Sebastian Mitchell, Clare Mullett, John and Virginia Murray, Oswyn Murray, Mark Norman, Jan Piggott, Froukje Pitstra, Jonathan Reinarz, Gabrielle Rendell, Eric Shanes, Bruce and Maggie Tattersall, Jevon Thistlewood, Michele Topham, Matthew Turi, Nicholas Webb, Andrew Wilton, Joan Winterkorn, Lucy Wood, Susan Worrall and Vicky Worsfold. Staff of the Bodleian, the Royal Institution, the British Library, the National Art Library, the National Gallery Archive, the University of Birmingham Cadbury Research Library, the Barclays Bank Archive, the London Metropolitan Archives and Coutts & Co. were active and prescient in their assistance. Likewise, my love and thanks go to my family, in particular my wife Kate Eustace who has once again put up with a lot, and advised sagely.

Permissions to quote from copyright material have been generously given by Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford; Bourlet; British Library Board; Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham; Lilly Library, University of Indiana; National Art Library, Victoria and Albert Museum; National Gallery Archives, London; National Library of Scotland; RIBA Drawings & Archive Collection, British Architectural Library; Royal Institution of Great Britain; Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. If I have inadvertently quoted copyright material without proper acknowledgement, I apologise and invite copyright holders to contact me. I would like to thank the John R. Murray Charitable Trust for a generous grant towards illustration costs. At Atlantic Books Ben Dupr, Toby Mundy and James Nightingale have been sources of strength and confidence. I thank them all.

James Hamilton

Kidlington, 2014

ILLUSTRATIONS

First section

Whalers (Boiling Blubber) Entangled in Flaw Ice, Endeavouring to Extricate Themselves (oil on canvas, 1845) by J. M. W. Turner. ( Tate, London 2014)

Second section

Paintings being delivered for selection to the Royal Academy, Trafalgar Square (wood engraving) from the Illustrated London News, 1866 (Time & Life Pictures / Getty Images)

Study for Patrons and Lovers of Art (oil on canvas, 18261830) by Pieter Christoffel Wonder. ( National Portrait Gallery, London)

INTRODUCTION: A SHARP AND SHINING POINT

Standing on a table, the better to be seen by his audience, a burly man raises a sledge-hammer above his head and slams it down onto an anvil. Thomas Boys, the print dealer of Oxford Street, London, retiring in 1855 after forty-five years in the trade, had hired an executioner as party entertainment in his glittering gas-lit gallery to smash to pieces a dozen or more engraved printing plates of popular images by popular artists. Like magpies shot by a farmer, the shattered metal pieces were then nailed up for all to see. The object of the exercise, ran its Times advertisement, was to destroy the plates utterly, to give a sterling and lasting value to the existing copies, which by this means can never become common. Thus proceeded an event in which art and business, reputation and value, came together in an attempt to keep these four boisterous creatures together and in trim. On the anvil, past practices in the business of art were shattered into pieces, and new systems wrought. This was a consequence of arts industrial revolution; it had left the quiet of the studio far behind and entered the furious market. It showed that art had a redoubled economic purpose, a sharply focused aggression, and was a significant factor in national and international trade.

This book explores how art in the nineteenth century was made and paid for, and how it evolved in the face of fluctuating money supply, the turns of fashion, and the new demands of a growing middle class, prominent among whom were the artists themselves. An endless subject such as this remains synoptic and laced with story and metaphor: it looks at networks, friendships and enmities, at debts, disasters and loyalties; and dances across a complex landscape in which art, literature, invention and entrepreneurship are the hedges and ditches, villages and townships that separate and maintain a shifting population. Complex social and institutional structures evolved across the nation, embracing art and music, drama and science. New clubs and academies, societies and institutions articulated the lives and motivations of the ingenious, ambitious and quarrelsome people who inhabited them. Together, they created a potent mixture to hurry the rapid growth of culture in Britain.

![Harvie Christopher - Nineteenth-century Britain: a very short introduction ; [in memorian Colin Matthew]](/uploads/posts/book/137651/thumbs/harvie-christopher-nineteenth-century-britain-a.jpg)