Preface

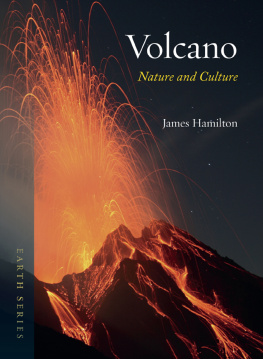

Maybe it is not the destructiveness of the volcano that pleases most, though everyone loves a conflagration, but its defiance of the law of gravity to which every inorganic mass is subject... Perhaps we attend to a volcano for its elevation, like ballet. How high the molten rocks soar, how far above the mushrooming cloud. The thrill is that the mountain blows itself up, even if it must then like the dancer return to earth; even if it does not simply descend it falls, it falls on us.

Susan Sontag, The Volcano Lover

The eruption in April 2010 beneath the Icelandic glacier Eyjafjallajkull was a salutary reminder of the power of volcanoes. This is a small volcano, but nevertheless its cloud of smoke and ash, directed across Britain and the Continent by an inconvenient prevailing wind, drove a crucial British General Election out of the main headlines for nearly a week, and threw world air traffic into temporary disarray.

We live on the same cooling planet that experienced eruptions of Santorini around 1620 BC, Vesuvius in AD 79 and 1631, Hekla in 17668, Tambora in 1815 and Krakatoa in 1883, all to devastating effect. These eruptions are part of a continual geological process, and what Eyjafjallajkull brought clearly to mind is that an ill-timed volcanic eruption of sufficient scale and unfortunate location will have such an immediate effect on the earths climate and economy as to make global warming seem slow and dull by comparison.

At any time theres a volcano erupting somehow, somewhere, with clouds of ash, and the accompanying thunder and lightning obbligato. What the Icelandic eruption did was to bring home some new understanding of the power of volcanoes, and of the fragility of our planet.

This book, which has grown out of the exhibition Volcano: From Turner to Warhol held in 2010 at Compton Verney, Warwick shire, explores artists and writers perception of volcanoes and its change over time.

1 The Whole Sea Boiled and Blazed

When we follow humanity in its earliest forms, creeping tentatively out from the African Rift Valley or, later, from what is now Australia, and moving gradually and ignorantly across the oceans by means of Continental Drift, we are traversing a period of two and a half million years or more. Adding on another ten or twelve thousand years, a blink of an eye by comparison, we can watch settlement in the Middle East, in the Americas, continental Europe and Southeast Asia. Here we arrive at the beginnings of ritual, the making of tools, and the first groupings of people cooperating to develop agriculture, the beginning of language and narrative, and the beginning too of accounting and writing. Across all these expanses of time volcanoes blasted from much the same weak points in the earths surface as they had blasted for aeons before. Its all the same to them. They carry on in much the same way today. Many weak points have cooled down and dried up, but the map of the earths cracks, now, bears a clear relationship to the map of the crust before Continental Drift, and is a direct product of the earths cooling movements.

Volcanoes were at work long before any form of humanity began to populate the planet and take notice. Thus to human history, though both localized and scattered, they are a given, constant presence. As the most violent terrestrial outrage that the planet can offer and humanity can witness, volcanic action may thus be the source of the first faint distant tracings of narrative on human memory.

If the residents of atal Hyk had developed a narrative tradition in which the volcano played a part, it has not come down to us. It is not for another 4,000 years that myth begins to shade into history when the volcano Santorini, now named Thera, the island in the Aegean Sea more or less equidistant between mainland Greece and Turkey, exploded around 1620 BC in what was the greatest event of natural destruction in recorded human history. Nearby Akrotiri was buried under lava and ash, while the tsunami that the eruption generated grew into a ten-metre high wave. This, after an unbroken run to Crete, cast itself on Knossos. The immediate destruction was one of the factors that precipitated the downfall of the Minoan civilization and, radiating in all directions, the tsunami brought havoc to the Aegean and its littoral. The Santorini eruption is one of the suggested causes of the disappearance of Atlantis if, indeed, Atlantis ever existed.

A group of volcanoes whose perturbations also left their traces on classical myth are the Lipari islands, a volcanic chain north of Sicily. The southernmost of these, Vulcano, which passed through a long eruptive period around 400 BC, was explained in Greek (and Roman) myth as the furnace and forge of Hephaistos, the god of fire, or his Roman equivalent, Vulcan. When the mountain erupted, as it did regularly in classical times, it was thought to signal that Hephaistos was at work. The Lipari islands were both deadly and convenient, as Demeter (Roman: Ceres), the goddess of the fertility of the earth, used them, and their near Tossing and turning still, he causes the ructions and eruptions that are a regular and continuing feature of Etna. Taking the myth of the Cyclopes yet deeper, the single, circular eye of this beast is reflected in the single, circular form of the crater: thus the volcano becomes the creature within. Does Homers epic tale, itself a late compilation of centuries of oral tradition, dimly throw back at us the shadow of earliest human memory and explication?

Other gods and demi-gods are buried under Vesuvius and Etna, according to myth. Enceladus rebelled against the gods and is buried beneath Etna, while his brother, Mimas, was buried by Hephaistos beneath Vesuvius. In the Aeneid, Virgils story of the origin of Rome written in the last two decades of the first century BC, we read one of the most dramatic accounts of an eruption in all classical literature. This is Virgils account of Etna in full flow:

The harbour there is spacious enough, and calm, for no winds reach it, but close by Etna thunders and its affrighting showers fall. Sometimes it ejects up to high heaven a cloud of utter black, bursting forth in a tornado of pitchy smoke with white-hot lava, and shoots tongues of flame to lick the stars. Sometimes the mountain tears out the rocks which are its entrails and hurls them upwards. Loud is the roar each time the pit in its depth boils over, and condenses this molten stone and hoists it high in the air.