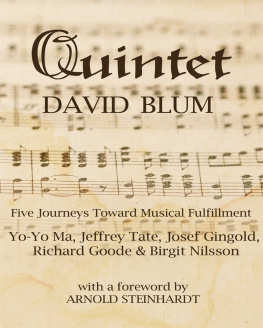

Quintet: Five Journeys Toward Musical Fulfillment

David Blum

Foreword by Arnold Steinhardt

Dzanc Books

Dzanc Books

1334 Woodbourne Street

Westland, MI 48186

www.dzancbooks.org

Copyright 1998 by David Blum

Foreword copyright 1999 by Cornell University used by permission

Chapters 1, 2, 3, and 4 originally appeared in The New Yorker. An abridged version of chapter 5 appeared in The New York Times on July 23, 1995.

All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher.

Published 2013 by Dzanc Books

A Dzanc Books rEprint Series Selection

eBooks ISBN-13: 978-1-938103-86-5

eBook Cover Photo by Awarding Book Covers

For the formation of the artist, the first prerequisite should be the development of the human being.

Franz Liszt

Each of the stories of these five remarkable musicians traces a journey in which musical and personal development are inseparable. A struggle is waged that eventually leads, often in unforseen ways, to greater human and artistic fulfillment. In every case, success is measured in terms that are internal as well as external.

David Blum

CONTENTS

[1]

A Process Larger than Oneself

Profile of the cellist Yo-Yo Ma

[2]

Walking to the Pavilion

Profile of the conductor Jeffrey Tate

[3]

A Gold Coin 75

Profile of the violinist Josef Gingold

[4]

Going to the Core 112

Profile of the pianist Richard Goode

[5]

The Farm Girl and the Stones

Profile of the singer Birgit Nilsson

FOREWORD

Rereading these five portraits, brought together in the present collection for the first time since their original appearance in the New Yorker and the New York Times, I am all the more taken with their breadth, detail, and honesty. Yo-Yo Ma, Jeffrey Tate, Josef Gingold, Richard Goode, and Birgit Nilsson appear to have overcome the obstacles of shyness, privacy, and career management and allowed David Blum unreservedly into their lives. I was informed, stimulated, entertained, and movedsometimes to the point of outright laughter and, yes, even to tears. Having known and worked with all these musicians except Nilsson, I could hear their individual voices lifting off the printed page. Blum captures their inimitable self-expression, their turn of mind and fine shading of wit. And more significantly, he accompanies his subjects into the mysteries of the creative process, uncovering hidden connections and latent meaning for reader and subject alike. Jeffrey Tate commented: Davids deeply original and inspiring relationship to music gave me so much insight into what I was doing, why I was doing it, and its place in the nature of things.

Those of us destined to appear in print tend, instinctively, to adopt a defensive stance. Musicians are no exception to the rule, sometimes doling out bits and pieces of their thoughts and lives that serve their public and privately held images. I have often sensed an unspoken conflict of goals lurking behind the smiles and good cheer when note-makers meet wordsmiths. The writer seeks truth, even if unflattering and painful to the subject. The musician also values truth, but preferably an alluring and glamorous version so that he or she might be bathed in a more favorable light. Even for those musicians who earnestly want to tell their whole story, warts and all, crucial elements may never see the light of day. There are writers who seek to dramatize or sensationalize for effect, and there are those who are unwilling or simply incapable of sallying forth into deep waters. Often we are left with the superficial, the banal. Quintets profiles stand in marked contrast.

As I ask myself how David Blum managed to create studies of such depth and scope, the intense, rather awkward adolescent I knew nearly half a century ago spontaneously comes to mind. By the time I met David he was a seventeen-year-old composer with a considerable body of work already behind him. Among his works are a ballet score to Cyrano de Bergerac, two operas, symphonic works, tone poems, and several books of songs. In the dual legacy he left, those principles so critical to composingoriginality, clarity, proportion, and expressive nuanceimprinted themselves on both his writing and music-making.

Our first musical encounter took place in his parents living room where David somehow cajoled several young musicians into rehearsing works for chamber orchestra. His face flushed and uplifted with the discovery of new treasures, David led us for the first time through a host of works from Mozarts Eine Kleine Nachtmusik to Wagners Siegfried Idyll. Looking back on that experience, I see that the ardor, the urgency that we all shared might have evoked patronizing smiles from any adults present. Teenagers! they probably muttered with the knowledge that youthful excess would give way to a reasonable and predictable existence. Most of the youngsters in that living room undoubtedly did settle down quietly. But David never seemed to acquire the calluses that time and repetition bring to the senses. His response to things of beauty and meaningthe engines that seem to have driven his liferemained fresh and charged.

From those embryonic living room rehearsals evolved a series of live television performances. David made his conducting debut in 1952 with his Youth Orchestra. A decade later, he founded the Ester-hazy Orchestra with Pablo Casals as honorary president. This orchestra became one of New Yorks finest chamber ensembles. The Blum-Esterhazy Orchestra recordings made more than twenty-five years ago are treasured by many for their Haydn interpretations.

Among the seminal influences in Davids musical life, one figure towers above the rest. David first heard Casals conduct at the Prades Festival. It was a transformative experience. Subsequently, his warm friendship with the maestro took him on numerous occasions to Puerto Rico where they had probing and far-ranging conversations. In the early 1960s David attended a series of master classes in Zermatt, Berkeley, and the Marlboro Music Festival, observing and notetaking for his own sake to learn from this great artist and teacher. The conversations, observations, andperhaps most important of allCasalss profound influence on Davids actual music-making, became the incisive analytical groundwork for Davids first book, Casals and the Art of Interpretation, a distillation of Casalss musical legacy. This work launched David into a major writing career.

The relationship between performer and music was central to Blums thinking. He refined his craft over the years, interviewing and writing profiles for the Strad, BBC Magazine, and the New York Times about artists with whom he felt a keen affinityincluding Igor Ois-trakh, Kyung-Wha Chung, Felix Galimir, Bernard Greenhouse, Bruno Giuranna, Richard Stolzman, Michael Tree, and Dawn Upshaw. He went on to write two more books: a biography, Paul Tortelier, and The Art of Quartet Playing: The Guarneri Quartet in Conversation with David Blum.

When one spends a lifetime in a career that demands facing interviewers of every description, a David Blum encounter stands out with a rare and provocative glow. I know this from the direct experience of thoughtful and searching conversations we held in preparation for the Guarneri Quartet book and later for a Strad article about my reflections on Schubert. David had a way of getting at the elusive beauty of a work, often asking not just one but a series of interrelated questions to probe beyond the expected. Absent were mechanical questions. A more typical query might lead into the architecture of music: What made the wild Great Fugue at the end of Beethovens String Quartet Opus 130 so structurally important, and why, under pressure from his publisher, was he so willing to replace it with a lighter weight movement? Or, why did Schubert feel compelled to alter his song, Sei mir gegrsst, when it appears in his

Next page