A LSO BY D AVID B LUM

C ASALS AND THE A RT OF I NTERPRETATION

P AUL T ORTELIER : A S ELF -P ORTRAIT

IN C ONVERSATION WITH D AVID B LUM

3 0000 10086245 1

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1986 by The Guarneri String Quartet and David Blum All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Blum, David

The art of quartet playing.

Discography: p.

1. Ensemble playing. 2. String quartetsInterpretation (phrasing, dynamics, etc.)

3. Guarneri Quartet. 4. MusiciansUnited StatesInterviews.

5. Beethoven, Ludwig van, 17701827. Quartets, strings, no. 14, op. 131, C minor. I. Title.

MT728.B6 1986 785.70471 85-45796

eISBN: 978-0-307-83180-4

v3.1

Do you think I worry about your lousy fiddle when the spirit speaks to me?

Beethoven to Schuppanzigh, in response

to his complaint about difficulties encountered

when playing one of the quartets

CONTENTS

PREFACE

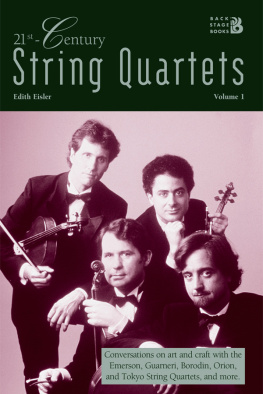

This book is a study in depth of the art of string quartet playing. The members of the Guarneri Quartet have brought to this work their experience both as individuals and as an ensemble of twenty years duration. They share here the exploration into interpretation to which each of them is passionately committed; they open the door to their workshop so that the reader may closely observe the process by which a performance is shaped.

Most of the material is dealt with in round-table discussions. Although I have arranged it in categories, all is interrelated; aspects of technique are invariably dealt with as means to expressive ends. As with all outstanding artists, the Quartet members musical conceptions are powerful, deeply rooted, and occasionally unconventional. If their views are sometimes expressed in highly subjective ways, this is only as it should be.

A quartet can be no stronger than the individuals who compose it; I have therefore asked each playera consummate instrumentalist in his own rightto tell something of his own background of studies and precepts of teaching. These interviews, entitled Four Voices, begin with David Soyer and build from the cello upwards; they inevitably encompass essential principles of string playing in general. (A short glossary may be found at the back of the book for the benefit of those readers not acquainted with string-playing terminology.)

In selecting Beethovens Quartet in C-sharp minor for detailed study in the final chapter, the Quartet pays homage to a supreme masterpiece while at the same time drawing together many strands of the book in relation to the interpretation of a single work.

My first encounter with a member of the Guarneri Quartet occurred in 1952 when I formed a young players chamber orchestra in Los Angeles in which Arnold Steinhardt took part. I was sixteen at the time, Arnold fifteen. Twelve years laterjust prior to the Quartets formationI had the pleasure of welcoming both John Dalley and Arnold as participants in the Esterhazy Orchestra during its first American tour, Arnold performing as soloist. I made the friendship of David Soyer and Michael Tree at Marlboro in the early 1960s.

Two decades later I suggested to the Quartet players that we create this book together. For that purpose, I accompanied them on tours in America and Europe. The conversations took place in hotels, motels, restaurants, green rooms, airplanes, trains, and cars (all five of us plus instruments and luggage packed into a single vehicle speeding across the Arizona desert); on occasion we were able to meet in the tranquility of my home near Geneva.

My work on this book was greatly eased by the fact that the members of the Guarneri Quartet remain good-natured in their mutual relationships to an extent that is rare for any chamber-music ensemble, much less for one of such exceptional longevity. This is due above all to the deep and abiding respect each player has for his colleagues. They know too that good relations in the personal as in the artistic realm dont always come of themselves, but must be worked for. They find it important to preserve their independence as much as possible. Summers are reserved exclusively for their families, and when on tour, they often travel separately and stay in different hotels. John Dalley, the most introverted of the four (though not so on the concert platform), will sometimes disappear entirely between concerts, mysteriously surfacing again at the appointed hour.

At rehearsals criticism is meted out equally by each member with a frankness that would far surpass the level of tolerance within most other ensembles. Yet the atmosphere is astonishingly free of tension. At times a point may be stubbornly argued, but the overriding spirit is one of patience and open-mindedness. A typical Guarneri rehearsal on tour takes place in a motel room, music strewn over beds and chairs, Michael Tree in tennis garb, and all the players in the most casual and unlikely poses for serious music making. Yet once bow touches string, they give the task in hand their total concentration. A piece revived from their past repertoire will be played through from first note to last and commented upon wherever necessary. But most revelatory is the way in which these rehearsals preserve a sense of musical continuity. Despite the frequent stopping and starting, one doesnt feel that the flow of the work is substantially interrupted. A ritardando or moment of rubato may sometimes be referred to as excessive but then not gone over again; the players can rely upon their innate taste and years of experience in working together to give the passage its just proportions in performance. The piece emerges from the rehearsal point, carefully restudied and ready to be fully savored on the concert stage.

A striking characteristic of these four musicians is their individual and collective sense of humor, which, given the difficulties inherent in two decades of touring and the presentation of over two thousand concerts, provides a blessed relief from stress. Jokes are traded around the clockgentle or satiric, witty or corny, at all events irresistible and the bane of the Quartets interviewer.

The joyous play on words, the natural high spirits, the ebullience typical of the daily life of the Guarneri Quartet find a parallel in their music making. The players technical command and level of musical development allow them to enjoy a measure of freedom at the heights, to disport with the musicnot arbitrarily and irreverently, but creatively and imaginatively, in the spirit and at the service of the artwork. One is reminded of Schiller: Man is completely human only when he is at playa truth that strikes home time and again in Guarneri Quartet performances, whether in the banter of the Presto from Beethovens Opus 130, the yearning of the Adagio from Schumanns A-minor Quartet, the passion of the Finale of Beethovens Opus 132, or the mystery of the pianissimo passages in the first movement of Schuberts G-major Quartet that quietly herald the formation of a new cosmos.

For the Guarneri Quartet every work is a living entity; no two performances are exactly alike. Their conceptions are always evolving. For this reason their interpretative markings (enclosed within parentheses in the music examples) should not be regarded as definitive but as expressions of the moment, subject to variations in light and shade.